Topics in this EM Quick Hits podcast

Matthew MacArthur on the role of occipital nerve block for the treatment of headache (1:32)

Ian Chernoff on the role of POCUS in patients with pulmonary embolism (10:25)

Hans Rosenberg on identification and management of myelopathy in the ED (29:13)

Shawn Segeren on the importance of the recorder during resuscitations (35:27)

Brit Long on incidental neutropenia (39:20)

Kylie Booth on Emergency Medicine peer programs (49:50)

Podcast production, editing and sound design by Anton Helman

Podcast content, written summary & blog post by Brandon Ng, Brit Long, Mathew MacArthur, edited by Anton Helman, June, 2025

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A. MacArthur, M. Chernoff, I. Rosenberg, H. Segeren, S. Long, B. Booth, K. EM Quick Hits 65 – Occipital Nerve Block, PoCUS in Pulmonary Embolism, Myelopathy, Team Resuscitation, Incidental Neutropenia, Peer Programs. Emergency Medicine Cases. June, 2025. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-june-2025/. Accessed June 5, 2025.

Indications, evidence, techniques and tips of occipital nerve block for headache management

Indications for occipital nerve block

- Suspected diagnosis of occipital neuralgia: Recurrent sharp stabbing headache with reproducible tenderness on percussion in the occipital nerve distribution.

- ICHD diagnostic criteria for occipital neuralgia includes symptom relief from nerve block.

- Other occipital headaches, including occipital migraines, cervicogenic headaches, cluster headaches.

- Consider occipital nerve block especially if patient fails first line treatments, and if headaches are predominantly occipital.

Source: Levin M. Nerve blocks in the treatment of headache. Neurotherapeutics. 2010 Apr;7(2):197-203

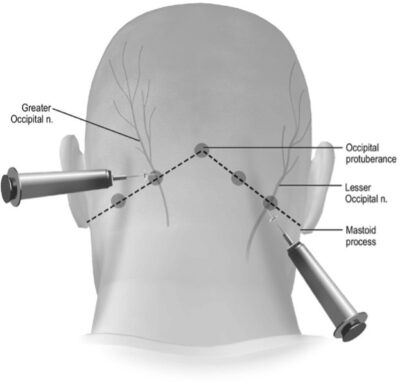

Occipital nerve block technique

- Medication: ~3cc of 2% lidocaine (± dexamethasone or bupivacaine).

- Landmarks:

- Palpate for the occipital protuberance and the mastoid process.

- Draw a linear line between the two landmarks = superior nuchal line of the occipital bone.

- Greater occipital nerve (GON) ≈ 1/3 from midline to mastoid process.

- Lesser occipital nerve (LON) ≈ 2/3 from midline to mastoid process.

- The GON & LON can also be landmarked using palpation or ultrasound to identify the occipital artery (the GON runs medially to artery), or by percussing along the superior nuchal line and injecting at the point of maximal tenderness.

- Injection:

- Use a small, 25–27G needle,

- Advance needle perpendicularly to periosteum, then withdraw slightly and aspirate.

- Inject ~1cc over nerve, and fan/reposition the needle to inject 1cc medial and 1cc lateral to the nerve.

- Always inject on or just above the superior nuchal line.

A single injection can halt the dysregulated pain signaling and provide sustained headache relief even after the anesthetic wears off.

Evidence for occipital nerve blocks for headache

- Based on recent systematic reviews, the current RCT evidence for occipital nerve block shows statistically significant reductions in occipital headache intensity and frequency, both immediately and over the weeks that follow

- Also no serious adverse events

- However the evidence is limited by small sample sizes, with variations between different nerve block techniques (eg choice of local anesthetic agent, combined local anesthetic + steroid vs local anesthetic only, ultrasound guided vs landmark based approach, use of control treatment vs placebo, etc)

1. Systematic review in 2023 of Nerve Blocks for Occipital Headaches (Evans et al)

- Included studies of occipital nerve blocks for any headaches that had occipital pain or tenderness (mostly cervicogenic headaches or migraines)

- 12 RCTs with 586 patients

- Overall statistically significant reduction in headache severity at 5-20 minutes post injection (-2.88 [95% CI -3.53, -2.23])

- Also statistically significant reduction in headache severity between 1-6 weeks (-3.74 [95% CI -3.98, -3.50])

2. Systematic review in 2024 of Occipital Nerve Block for Chronic Migraine (Mustafa et al)

- Not focused specifically on acute treatment of headache, rather focused on use of occipital nerve block for patients suffering from chronic migraines

- 8 RCTs with 268 patients

- After 1 month, statistically significant reduction in headache intensity (-0.653, 95% CI [-0.996 to -0.311]) and frequency (-0.755 [95% CI -1.133 to -0.377])

Bottom Line: Occipital nerve block is safe, fast, and often effective with proper landmarking. Consider its use for occipital neuralgia and as a second-line treatment for occipital migraines/headaches refractory to standard ED therapy.

- ICHD-3 Occipital Neuralgia: https://ichd-3.org/13-painful-cranial-neuropathies-and-other-facial-pains/13-4-occipital-neuralgia/

- Evans AG, Joseph KS, Samouil MM, Hill DS, Ibrahim MM, Assi PE, Joseph JT, Kassis SA. Nerve blocks for occipital headaches: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2023 Apr-Jun;39(2):170-180. doi: 10.4103/joacp.JOACP_62_21. Epub 2023 Apr 25. PMID: 37564833; PMCID: PMC10410037.

- Mustafa, M.S., bin Amin, S., Kumar, A. et al.Assessing the effectiveness of greater occipital nerve block in chronic migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol 24, 330 (2024).

- Levin M. Nerve blocks in the treatment of headache. Neurotherapeutics. 2010 Apr;7(2):197-203. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.03.001. PMID: 20430319; PMCID: PMC5084101.

PoCUS in the diagnosis and risk stratification of pulmonary embolism

This is a companion podcast segment to our 2-part podcast on Management of Pulmonary Embolism: Management of Intermediate Risk PE, and Management of High Risk PE

POCUS may offer high-yield prognostic information for intermediate-risk PE patients with CT, as well as diagnostic information for high-risk PE patients who are too unstable for CT.

All basic PoCUS views have findings that support the diagnosis of RV strain in PE:

- Subcostal: IVC distention

- Parasternal long axis: D-sign and RV enlargement

- Apical 4-Chamber View (most useful):

- TAPSE <1.6cm (abnormal longitudinal RV contraction): Measured using M-mode placed through the lateral tricuspid annulus.

- RV free wall hypokinesis (dysfunctional radial RV contraction): More sensitive than TAPSE in detecting RV strain.

- RV to LV ratio ≥1

Advanced Signs:

- Paradoxical septal motion (intraventricular septum bowing into the LV).

- McConnell’s Sign (RV free wall akinesis with apical sparing): 97-99% specificity but found in ~25% of patients with PE.

- Present in acute PE but not in chronic RV pathologies e.g. pulmonary hypertension.

- Caveat: can also be present in RV infarction.

- Clot in transit through the RV or RA (rare but diagnostic).

- Pulmonary artery acceleration time <60ms (via pulse wave doppler on parasternal short axis view, part of the “60/60 rule”).

- In acute PE, blood flow within the pulmonary artery reaches peak velocity quickly (<60ms) as the RV has yet to accommodate to the acute increase in RV afterload.

- In chronic PE, pulmonary artery acceleration time is slower as the RV accommodates the increased outflow resistance through RV hypertrophy.

- Presence of early systolic notching (via pulse wave doppler on parasternal short axis view).

- Presence of an acute PE causes a characteristic early retrograde pressure wave or “early systolic notching” as blood entering the pulmonary artery strikes and rebounds off the PE obstruction.

- In pulmonary hypertension or lower risk/distal PE, the rebound pressure wave returns in a delayed fashion, causing “mid systolic notching.”

- Tricuspid regurgitation gradient <60mmHg (via colour and continuous wave doppler on multiple views, part of the “60/60 rule”).

- In chronic PE/pulmonary hypertension the RV accommodates via hypertrophy and produces higher peak TR gradients as compared to a non-hypertrophic RV in an acute PE which struggles against the acute increase in RV afterload.

Approach:

- Intermediate risk PE: PoCUS improves the detection of RV strain as compared to CTPA alone (Dudzinski et al. 2017).

- High risk PE: PoCUS is highly sensitive in revealing PE as a cause of a patient’s peri-arrest state.

- Up to 100% specificity for PE as the cause of shock if both cardiac and leg ultrasound were positive for signs of RV strain and DVT respectively (Nazerian et al. 2018).

- ESC guidelines support immediate thrombolysis without further testing if there is echocardiographic evidence of RV dysfunction in an unstable patient (Konstantinides et al. 2020).

- Distinguishing acute vs. chronic RV dysfunction is key. For example:

- RV wall thickening >5mm on subcostal/parasternal long axis view = chronic

- Identifying McConnell’s sign/clot in transit, early systolic notching, meeting the “60/60 rule” = acute

Pitfalls:

- Foreshortening of the RV on apical view can lead to overestimation of RV size.

- If the entire heart appears rounder/broader (LV not elliptical), move the probe one interspace caudally and laterally.

- Mismatch between POCUS and CT findings with clinical picture? Re-evaluate.

Bottom Line: In intermediate risk PE, PoCUS may help risk stratify. In high-risk or crashing patients PoCUS can be diagnostic and guide immediate reperfusion decisions.

- Fields JM, Davis J, Girson L, Au A, Potts J, Morgan CJ, Vetter I, Riesenberg LA. Transthoracic Echocardiography for Diagnosing Pulmonary Embolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017 Jul;30(7):714-723.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.03.004. Epub 2017 May 9. PMID: 28495379.

- Dudzinski DM, Hariharan P, Parry BA, Chang Y, Kabrhel C. Assessment of Right Ventricular Strain by Computed Tomography Versus Echocardiography in Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Acad Emerg Med. 2017 Mar;24(3):337-343. doi: 10.1111/acem.13108. PMID: 27664798.

- Nazerian P, Volpicelli G, Gigli C, Lamorte A, Grifoni S, Vanni S. Diagnostic accuracy of focused cardiac and venous ultrasound examinations in patients with shock and suspected pulmonary embolism. Intern Emerg Med. 2018 Jun;13(4):567-574. doi: 10.1007/s11739-017-1681-1. Epub 2017 May 24. PMID: 28540661.

- Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, Bueno H, Geersing GJ, Harjola VP, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Jennings CS, Jiménez D, Kucher N, Lang IM, Lankeit M, Lorusso R, Mazzolai L, Meneveau N, Ní Áinle F, Prandoni P, Pruszczyk P, Righini M, Torbicki A, Van Belle E, Zamorano JL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 21;41(4):543-603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. PMID: 31504429.

Myopathy: Tips for recognition of spinal cord emergencies

Myelopathy = spinal cord dysfunction from compressive or non-compressive causes.

- Compressive Causes: Degenerative cervical myelopathy, central cord syndrome, epidural abscess, tumor, vascular malformations

- Non-Compressive Causes: Myelitis (infectious/inflammatory/autoimmune), B12 deficiency, radiation, toxins, paraneoplastic syndromes

Key Clinical Clues:

- Urinary retention

- Dermatomal sensory loss

- Upper motor neuron signs: hyperreflexia, clonus, Babinski sign, spastic gait, Hoffman’s sign – flicking nail of middle finger → thumb/index finger adduction = cervical cord disease

Workup of suspected myelopathy

- MRI: Whole spine MRI is usually recommended to screen for multifocal disease/”skip” lesions

- LP: If non-compressive etiology suspected to help identify inflammatory/infectious causes

ED management of suspected myelopathy

- Compressive: Neurosurgical consult ± dexamethasone (for malignant compression) or antibiotics (for suspected abscess).

- Non-compressive: Neurology consult ± steroids or immunotherapy (in consultation with neurology).

- Rapidly progressive symptoms require urgent imaging and referral to sites with neurosurgical and neurology services.

- Outpatient workup may be appropriate in stable patients with mild progressive symptoms, although delayed diagnosis may risk irreversible deficits.

Bottom Line: Upper motor neuron signs with dermatomal sensory loss should raise suspicion for myelopathy. MRI is an essential diagnostic tool and patients may require whole spine imaging. Rapid recognition and referral to neurosurgery or neurology are critical for preventing irreversible deficits.

- MacDonald Z, Ferguson E, Rosenberg H. Just the facts: emergency department approach to myelopathy. CJEM. 2024 Dec;26(12):851-853. doi: 10.1007/s43678-024-00763-8. Epub 2024 Sep 5. PMID: 39237730.

Team dynamics in resuscitation: The important role of the recorder

- In team resuscitations, we may overlook a critical role: the recorder/documenter who may be the most important team member in resuscitations

- The recorder, often a nurse (junior or senior), is usually the only team member not locked into a single task, giving them a unique vantage point.

- It’s frequently the recorder who notices vital sign trends, timing lapses, and key clinical shifts—often before anyone else.

- In stretched teams without backups or specialty staff, the recorder becomes the anchor of situational awareness. This role can be referred to as the “situational awareness seat”.

- Recognizing and empowering this role may elevate team performance and improve patient care.

Tips for Resuscitation Team Leaders

- Make space for the recorder to speak up

- Ask the recorder questions such as: “Are you seeing anything I’m missing?”

- Recognize the key insights that this role has to offer as part of the team

Bottom Line: The recorder is not passive—when empowered and involved, they can elevate team performance and patient safety.

Incidental neutropenia: Practical considerations and when to act

- Normal adult absolute neutrophil count (ANC) for adults 1500-7000 cells/microL.

- Neutropenia: ANC < 1500; mild 1000-1500, moderate 500-1000, severe < 500.

- Prevalence 0-25% in healthy, asymptomatic individuals; depends on patient population, age, other conditions like autoimmune disorders.

- Incidental neutropenia – 25% will have ANC between 1000-1500.

- Underlying mechanism: decreased production, redistribution to vascular endothelium or the spleen, immune destruction.

- Two categories: malignant versus nonmalignant

- Malignancy: leukemias and myelodysplastic syndromes

- Nonmalignant:

- Most common causes of mild neutropenia in adults: Duffy-null associated neutrophil count (DANC; inherited cause, well appearing patient), dose-dependent drug-induced neutropenia, infections (usually viral).

- Inherited causes: DANC; several types in African, Middle East and Mediterranean descent; familial neutropenia and congenital neutropenia.

- Medications (most commonly cytotoxic or immunosuppressive medications, can be severe neutropenia)

- Infections: viral (EBV, HIV, hepatitis), bacteria, parasites, Rickettsia

- Usually transient/not severe

- Nutritional deficiency (B12, folate, copper)

- Veganism, IBD, post bariatric, alcohol use disorder

- Macrocytic anemia, not usually severe neutropenia

- Rheumatologic/autoimmune disorders

- Aplastic anemia

- Chronic idiopathic neutropenia

- Cyclic neutropenia

- Approach to incidental neutropenia

1) Clinical status of the patient and the suspected cause based on history and exam and

2) Laboratory testing with CBC and ANC, differential, other cell lines, and peripheral smear.

-

- Critically ill, febrile: antibiotics, blood cultures, admission. Obtain coagulation panel, LDH, fibrinogen, renal function. Be concerned about infection, TTP, DIC.

- If stable, use history and exam:

- Has this happened before? Is this due to a drug? If due to a medication and they look well and not severe neutropenia, drug may need to be discontinued but patient can be discharged. If prior episodes and they look well, not severe neutropenia, can discharge.

- If new and not due to a drug, consider the following:

- Active inflammatory issue or infection? Weight loss, night sweats, chills, fevers? History of cancer, a GI disorder or liver disease? Cyclic infections or aphthous ulcers (cyclic neutropenia)? Special diet issues or chronic alcohol use? Any substances that could have been modified with levamisole? Family history of neutropenia or hematologic issues? Ethnicity? Ulcers, jaundice, rash? Lymphadenopathy? Joint swelling/bone pain? Neurologic or psychiatric changes? Premature graying of the air, or skeletal or fingernails (combined with family history of neutropenia or unexplained childhood deaths concerning for congenital neutropenia)?

- If no severe neutropenia, asymptomatic, no worrisome findings on the smear may discharge with primary follow for repeat CBC; no emergent hematology necessary at this point. Other testing for primary provider: viral panels, liver panel, B12/folate/copper, inflammatory markers (rheumatologic disorders), blood typing.

- If the primary provider has completed their evaluation with these labs but no cause found and patient has continued neutropenia, hematology referral is likely necessary.

| Medications Associated with Neutropenia |

|

* Most commonly associated with neutropenia

- Frater JL. How I investigate neutropenia. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020 Jun;42 Suppl 1:121-132.

- Newburger PE, Dale DC. Evaluation and management of patients with isolated neutropenia. Semin Hematol. 2013 Jul;50(3):198-206.

- Long B, Koyfman A. Incidental neutropenia: An emergency medicine focused approach. Am J Emerg Med. 2025 Mar;89:190-194. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2024.12.039. Epub 2024 Dec 19. PMID: 39733655.

Emergency medicine peer programs

Peer programs provide support for emergency providers to consult a trusted EM colleague before, during or after a shift.

The Ontario Health Peer-to-Peer Program is a an example of a peer program with a 24/7 support line for Ontario ED physicians to speak with a trusted colleague in real time for assistance or advice.

The service is especially valuable for smaller centers where physicians are working under single coverage environments where a physician colleague is not available.

How The Ontario Peer-to-Peer program works

- Call CritiCall Ontario at: 1-800-668-4357

- Ask to speak with an “ED peer”

- It is appropriate to call before, during, or after a case—no patient ID/health card needed

Purpose of EM peer programs

- Provides clinical backup, emotional support, and decision clarity to clinicians in a peer-to-peer manner

- Fosters collegiality, combats isolation, and builds system-wide trust

Outcomes of the program include reported impact on physician wellness, increased rural locum uptake due to availability of peer support, and improved patient preparedness for transfer.

Bottom Line: EM peer programs are a model of compassionate, horizontal support to build sustainable EM practice—especially in rural and solo-coverage environments.

More about Ontario Peer to Peer Program

For more information and advice on setting up a peer program where you work, contact Dr. Kylie Booth at EDPeer@ontariohealth.ca

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare

Leave A Comment