Topics in this EM Quick Hits podcast

Justin Morgenstern on fluids in acute pancreatitis – WATERFALL Trial (0:38)

Leeor Sommer on nasal fractures in the emergency department (6:45)

Christina Shenvi on acute delirium identification and workup (15:21)

Sheldon Cheskes & Rohit Mohindra on the DOSE VF trial (25:23)

Nour Khatib & Kari Sampsel on intimiate partner violence (61:13)

Podcast content, production, editing and sound design by Anton Helman

Podcast written summary & blog post by Raymond Cho; edited by Anton Helman

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A. Morgenstern, J. Sommer, L. Shenvi, C. Cheskes, S. Mohindra, R. Khatib, N. Sampsel, K. EM Quick Hits 44 – Fluids in Pancreatitis, Nasal Fractures, Delirium, DOSE VF, Intimate Partner Violence. Emergency Medicine Cases. November, 2022. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-november-2022/. Accessed April 25, 2024.

Fluids in Acute Pancreatitis – WATERFALL Trial

- Background: ED management of acute pancreatitis has traditionally focused on aggressive fluid resuscitation; however, recent evidence suggests potential harm in this approach

- Clinical question: Does moderate vs. aggressive fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis decrease progression to moderate/severe pancreatitis?

- Methods/Outcomes: The WATERFALL trial is a randomized control trial of 249 patients with the control group receiving a ringer’s lactate (RL) bolus of 20 cc/kg followed by 3.0 cc/kg/hr, and the intervention group receiving 10 cc/kg bolus if hypovolemic or no bolus if euvolemic followed by 1.5 cc/kg/hr. Primary outcome was progression to moderate-to-severe acute pancreatitis, and primary safety endpoint was fluid overload.

- Results: 17.3% in the moderate and 22.1% in the aggressive fluid group progressed to moderate/severe pancreatitis (aRR 1.30, 95% CI 0.78-2.18)

- The trial was stopped early as interim analysis showed a high incidence of fluid overload in the aggressive fluid group (20.5% vs. 6.3%, aRR 2.85, 95%CI 1.36-5.94)

- Author conclusions: Early aggressive fluid resuscitation resulted in a higher incidence of fluid overload without improvement in clinical outcomes

- Commentary: In the fluid management of acute pancreatitis, less is more. Use small boluses (e.g., 500 cc RL), and reassess after each bolus; note that this trial applies only to patients with mild pancreatitis and ensure your patient meets this inclusion criteria before abandoning IV fluid resuscitation altogether.

- de-Madaria E et al. Aggressive or Moderate Fluid Resuscitation in Acute Pancreatitis (WATERFALL). NEJM 2022. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2202884

- Morgenstern, J. (2022, November 1). Research roundup October 2022. First10EM. https://first10em.com/research-roundup-october-2022/

- Swaminathan, A. (2022, September 29). Less is more . . . Again: Speed of IV fluid administration in pancreatitis (Waterfall trial). REBEL EM – Emergency Medicine Blog. https://rebelem.com/less-is-more-again-speed-of-iv-fluid-administration-in-pancreatitis-waterfall-trial/

Nasal Fractures in the Emergency Department

Clinical Assessment

- Always remember to assess for septal hematoma, which if unrecognized, can result in necrosis to the nasal cartilage, cosmetic deformities, and nasal perforation

- Assess the patient from 2 planes (above and in front) to identify subtle deformities/deviation

- Ask the patient and their entourage whether the nose appears different from baseline

Diagnosis

- Nasal fracture is a clinical diagnosis

- For the majority of isolated nasal injuries, there is little role for imaging as it does not alter management in non-displaced fractures, and deviated cartilage will not appear on X-rays anyway

- In patients who may require open reduction of a nasal fracture, defer the decision to perform a CT scan to the specialist who will be performing the surgery

Management

- Regional anesthesia with infraorbital and external nasal nerve block OR procedural sedation

- Closed reduction of nasal fractures video

- Mondin, V., Rinaldo, A., & Ferlito, A. (2005). Management of nasal bone fractures. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 26(3), 181-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.11.006

- Rubinstein, B. (2000). Management of nasal fractures. Archives of Family Medicine, 9(8), 738-742. https://doi.org/10.1001/archfami.9.8.738

Acute Delirium Identification and Workup

Background

- Acute delirium is a common ED presentation but missed up to 75% of the time

- Characterized by waxing and waning alteration in mental status, inattention, altered level of consciousness

- Subtypes of delirium: hyperactive delirium, hypoactive delirium (92% of cases of delirium and often missed)

Identification of delirium

- Features that increase risk for delirium: cognitive impairment, difficulty with ADLs, hearing impairment

- Screening tools

- Delirium triage screen (sensitive, not specific): altered LoC, inattention

- Brief confusion assessment method (97% specific): altered mental status/fluctuating course, inattention, altered LoC

Differential diagnosis

- Medication: new medications e.g., anticholinergics, muscle relaxants, sedatives, steroids, etc.

- Infections: respiratory, urinary, CNS, skin/soft tissue infections

- Neurologic: neuro exam to assess for TIA, stroke, mass, etc.

- Metabolic: derangements in glucose, sodium, potassium, dehydration, AKI

- Cardiopulmonary: ACS, dissection, hypoxia, hypotension

- Toxicology/withdrawal: ETOH, ETOH withdrawal, non-intentional overdoses

- Other causes: pain, urinary/fecal retention, missing hearing or vision aids

Update 2022: A systematic review examining patients aged 65 or older who received neuroimaging at the time of ED assessment for delirium, confusion, or altered mental status found that 15.6% of these patients had an abnormal CT head. Anticoagulation did not have a significant pooled odds ratio for an abnormal CT (OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.43-3.25), but neurological deficit did have a significant pooled odds ratio for abnormal CT (OR 110.2, 95% CI 30.5-340.1). Abstract

- Rosenberg M, Carpenter CR, Bromley M, et al. Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. May 2014;63(5):e7-e25. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24746437

- Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med. Mar 2009;16(3):193-200. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21496140

- Shenvi, C., Kennedy, M., Austin, C. A., Wilson, M. P., Gerardi, M., & Schneider, S. (2020). Managing delirium and agitation in the older emergency department patient: The ADEPT tool. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 75(2), 136-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.07.023

DOSE VF Trial – Best of University of Toronto Emergency Medicine

Background

- Treatment-refractory ventricular fibrillation (VF) is a common problem with seemingly limited options as medications in our toolbox do not confer survival benefit

- Survival within 3 shocks is ~30%, but drops significantly after shocks 4-10 to ~12.5%

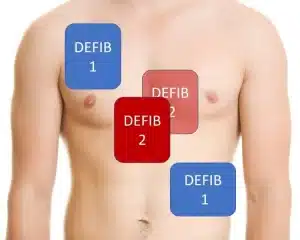

- Alternative strategies in refractory VF include a vector change (VC) of defibrillation pads from anterior-lateral (AL) position to anterior-posterior (AP) position, and double sequential external defibrillation (DSED). These strategies have been traditionally applied as a last-ditch effort, but this will predictably fail as too much time has passed since the onset of cardiac arrest.

- This study aims to evaluate the efficacy of the early application of DSED and VC defibrillation compared to standard defibrillation in treatment-refractory VF in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Design

- Cluster-randomized control trial with 6 paramedic services.; all patients received three successive defibrillation attempts with pads in standard AL position and if they remained in VF, were randomized to standard AL defibrillation (n = 136), VC defibrillation (n = 144), and DSED (n = 125).

- Inclusion criteria: Refractory VF after 3 consecutive standard defibrillations

- Exclusion criteria: < 18 years of age, DNR, traumatic arrest, drowning

- Enrolment was stopped early (n = 405) due to the feasibility concerns during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic

- Primary outcome: survival to hospital discharge

- Secondary outcomes: termination of VF, return of spontaneous circulation, modified Rankin Scale ≤ 2

Results

- Survival to hospital discharge for standard, VC, and DSED was 13.3%, 21.7%, and 30.4% respectively (p = 0.009)

- Secondary outcomes:

| Standard | VC | DSED | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Termination of VF | 67.7% | 79.9% | 84.0% |

| ROSC | 26.5% | 35.4% | 46.4% |

| Modified Rankin score ≤2 | 11.2% | 16.2% | 27.4% |

- Overall, DSED was superior to standard management in all primary and secondary outcomes, and VC was superior to standard management in VF termination and survival to hospital discharge but not neurologically intact survival

Critical appraisal

- The sensitivity analysis showed that the effect size of VC treatment is likely not reflective of true effect size, and higher rate of crossover back to standard treatment, which likely biased results

- All studies that show a new technique tend to show higher benefits than subsequent studies

- Several paramedic training and monitoring factors, including the emphasis on and monitoring of high-quality CPR and standardized training in DSED, may have influenced the results

- Blinding was impossible for the intervention; this limitation was minimized with monitoring of CPR quality, medications given, PCI, demographics (shown to be balanced across all three arms), and data assessors were blinded to the intervention

Considerations in the application of DSED/VC in refractory VF

- Defibrillator damage in DSED: theoretical damage can happen if both defibrillators are activated simultaneously to the millisecond; however, as they are being activated in sequence in DSED, there is almost no risk of damage if technique is applied correctly

- Immediate use of DSED/VC (rather than waiting for 3 standard shocks): not recommended as conversion and survival is already quite good in early VF arrest

- Other things to consider in refractory VF arrest: continuous high-quality CPR, limiting dose of epinephrine to 3 doses, amiodarone, esmolol, stellate ganglion block

Pad placement for double sequential defibrillation. Image courtesy of Dr. Mark Ramzy (@MRamzyDO)

Bottom Line: Double-sequential external defibrillation (and vector change in lower-resourced settings) is ready for prime time pending guideline recommendations. Use these strategies early in cardiac arrest immediately after 3 standard shocks have been delivered.

- Cheskes, S., Verbeek, P. R., Drennan, I. R., McLeod, S. L., Turner, L., Pinto, R., Feldman, M., Davis, M., Vaillancourt, C., Morrison, L. J., Dorian, P., & Scales, D. C. (2022). Defibrillation strategies for refractory ventricular fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2207304

- Cheskes, S., Dorian, P., Feldman, M., McLeod, S., Scales, D. C., Pinto, R., Turner, L., Morrison, L. J., Drennan, I. R., & Verbeek, P. R. (2020). Double sequential external defibrillation for refractory ventricular fibrillation: The DOSE VF pilot randomized controlled trial. Resuscitation, 150, 178-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.02.010

Intimate Partner Violence

- 38% of murders of all women worldwide are related to IPV, 44% of women murdered by their intimate partner visited the ED in the past year, and ED physicians only identified 5% of IPV cases

- CAEP recommendations:

- IPV should be recognized as having similar presentations as non-accidental trauma or child abuse

- IPV should be considered in patients with multiple visits for the same presentation, chronic pain, mental health concerns, substance use disorders

- Universal screening is encouraged in the ED (i.e., all genders, age groups, etc.)

- Treat IPV-related injuries similarly to that of other accidental traumas

- Refer all consenting patients to a specialized IPV treatment center

- In documenting IPV-related charts, avoid legal words and use clear, factual statements

- Final diagnosis should contain the term ‘IPV’

- Khatib, N., & Sampsel, K. (2022). CAEP position statement executive summary. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 24(7), 691-694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-022-00386-x

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare

In Ireland, we use Mechanical Compressions devices (Lucas 3). How Dr Cheskes would recommend the placement of the Anterior sternal pad? The posterior pad would be placed during the insertion of the back plate, increasing the insertion time and requires a very well chorgraphed team. Or maybe the MCD should be reserved for non VF/VT arrests?