In this episode on Whistler’s Update in Emergency Medicine Conference 2014 Highlights we have Chapter 1 with David Carr on his approach to Shock, including the RUSH protocol, followed by a discussion on Thrombolysis for Submassive Pulmonary Embolism. Then in Chapter 2 Lisa Thurgur presents a series of Toxicology Cases packed with pearls, pitfalls and surprises and reviews the use of Lipid Emulsion Therapy in toxicology. Finally in Chapter 3 Joel Yaphe reviews the most important articles from 2013 including the Targeted Temperature Managment post-arrest paper, the use of Tranexamic Acid for epistaxis, return to play concussion guidelines and clinical decision rules for subarachnoid hemorrhage. Another Whistler’s Update in Emergency Medicine Conference to remember……. [wpfilebase tag=file id=420 tpl=emc-play /][wpfilebase tag=file id=421 tpl=emc-play /][wpfilebase tag=file id=422 tpl=emc-play /][wpfilebase tag=file id=423 tpl=emc-mp3 /][wpfilebase tag=file id=424 tpl=emc-mp3 /][wpfilebase tag=file id=425 tpl=emc-mp3 /]

Published May, 2014 by Anton Helman

Cite this podcast as: Carr, D, Thurgur, L, Yaphe, J, Helman, A. Whistler Update in Emergency Medicine Conference 2014. Emergency Medicine Cases. May, 2014. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/episode-44-whistlers-update-in-emergency-medicine-conference-2014-highlights/. Accessed [date].

David Carr – Shock

Sepsis and Surviving Sepsis

Sepsis definitions:

SIRS is ≥2/4 of: T>38 or <36, HR>90, RR>20 or PaCO2>32, or WBC>12 or

Sepsis: SIRS + Infection

Septic Shock: Sepsis + hypotension after 2L bolus

Severe Sepsis: Sepsis + poor end organ perfusion (hypotension, high lactate, urine output <0.5mL/kg/hr, acute lung injury, high creatinine or bilirubin, low platelets or coagulopathy) Mortality rises with high lactate to 26.5% (Shaprio et al). Early recognition, resuscitation, treatment à decreased mortality.

Hypotension is not defined by the physician, but by the patient. There is no specific number if the perfusion is low – if there is cardiac or renal dysfunction or a high lactate, or other signs perfusion is inadequate, the pressure is too low even if it seems “normal”.

Keep it simple: Initial management of the first 3 hours is simple (measure lactate, get cultures, start antibiotics, and fluids!)

Push fluids – by IO if peripheral IV doesn’t happen: Intraosseous access has been shown to gain access faster than central line (Paxton Sept 2009 J Trauma).

Which fluid: Surviving sepsis campaign (2012) – crystalloids remain fluid of choice à 30 mL/kg bolus over 30-60 minutes. Consider transfusion for

Which Antibiotics? Give antibiotics ASAP, as soon as sepsis is recognized. Mortality increases each hour antibiotics are not given. Give >1 active agent, and give them quickly, not needing to wait for 1 to finish before the next one.

Respiratory Pathogens (ISDA 2007 guidelines):

1) Antipneumococcal/antipseudomonal agent AND

- Imipenem 0.5-1g IV q6-8

- Piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5 g iv q8h

- Cefepime 2g IV q8-12

2) Second agent

- Levofloxacin 750 mg iv q24h

- Aminoglycoside + azithromycin, adding Vancomycin 2g IV if MRSA suspected, or coexisting central line or medical device

Suspected abdominal infections: a) Amp + Gent + metronidazole b) Amp + ceftriaxone + metronidazole c) Pip-tazo or levofloxacin or moxifloxacin or imipenem + metronidazole d) Ceftriaxone + metronidazole *Avoid clindamycin: 75% resistance to B. frag and 40% to Group A strep

Unknown source: Vancomycin + Imipenem or Pip-tazo or Cefepime

When do you intubate? Early! Sepsis causes diffuse alveolar damage, leading to ARDS, and breathing actually uses high metabolic demands (up to 30%). For ARDS: Low tidal volume – 6ml/kg + Peep + plateau pressures <30

Septic Shock Bundle– within 6 hours: Give vasopressors (for persistent hypotension) to maintain a mean arterial pressure of >= 65 mmHg. If persistent hypotension, or initial lactate >4, measure CVP, or central venous O2, and follow lactate clearance.

Push dose pressors: Temporizing measures, until a central line. Phenylephrine peripherally (take 1mL of 10mg/mL into 100mL minibag, give 1 mL = 100 mcg q 2-5 min.

Norepinephrine vs Dopamine? Lots of evidence that mortality is higher in severe septic patients treated with dopamine versus norepinephrine (NEJM 2010 De backer), so max out on norepinephrine (5 to 20 ug/min) before adding a second agent.

Consider what you might be missing before adding a second pressor:

a) give more fluids

b) correct calcium if low

c) give blood if bleeding

d) consider intralipid for toxin shock

e) hydrocortisone, check thyroid

f) epinephrine for allergy (and glucagon if anaphylaxis on B-blocker)

g) t-PA for ?PE …

then add a second pressor. Which second pressor?

1) Is the heart beating well?

- Yes? à vasopressin, 0.03 U/in

- No, or HR low à epinephrine, 1-10U/min

2) Inotropic support

- Add dobutamine if ongoing hypoperfusion with reasonable MAP, start 2.5 U/kg/min

Who should get steroids? Corticosteroids are now less emphasized, but may have a role in hypotension refractory to shock. Start IV hydrocortisone 200mg/day.

RUSH Protocol

For a discussion and review of the RUSH protocol and POCUS in PE see Episode 18 – Point of Care Ultrasound Pearls & Pitfalls

Using Ultrasound in Shock: the RUSH protocol for evaluating shock using ultrasound (Perera EMerg Med Clin N Am 2010).

HIMAP: (Weingart et al 2006). Helps classify the type of shock and find the cause, whether hypoveolemic, cardiogenic, obstructive, or distributive).

Heart – look for effusion, tamponade, R heart strain, LVF IVC – look at fluid status (IVC 50%, correlates with a low CVP. IVC >2cm without inspiratory collapse, CVP >10) Morrison’s pouch/FAST – for free fuild Aorta – for AAA Pneumothorax

For Scott Weingart’s post on RUSH exam go here.

Submassive Pulmonary Embolism

While thrombolysis for massive PE has become standard of care, it’s still not so clear whether lytics are indicated for submassive PE. Definition of Submassive Pulmonary Embolism

- Acute PE without shock (SBP>90)

- either RV dysfunction or elevated Troponin (see below)

- RV dysfunction = 1 or more of – RV dilation or RV systolic dysfunction on echo or RV dilation on CT, elevated BNP, or ECG changes including new complete or incomplete RBBB, anteroseptal ST elevation or depression, or anteroseptal T-wave inversion

There have been 3 key trials looking at thrombolysis for submassive PE:

- MAPPET-3 trial 2002

- MOPPET trial 2013

- PEITHO trial 2014

MAPPET-3 Trial Management Strategies and Prognosis of Pulmonary Embolism-3 Trial (MAPPET-3) Investigators. Heparin plus alteplase compared with heparin alone in patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2002.

- Double blinded RCT of 256 patients

- Heparin plus 100 mg of alteplase vs heparin plus placebo over 2 hours

- Primary end point – in-hospital death or clinical deterioration requiring an escalation of treatment (catecholamine infusion, secondary thrombolysis, endotracheal intubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or emergency surgical embolectomy or thrombus fragmentation by catheter)

- No significant difference for in-hospital mortality (3% vs 2%)

- Less clinical deterioration in alteplase group (10% vs 25%)

- No significant difference in the incidence of major bleeding between the two groups

Conclusion: alteplase ‘may’ improve clinical course and prevent further clinical or hemodynamic deterioration

MOPPET Trial Moderate pulmonary embolism treated with thrombolysis (from the “MOPETT” Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2013 Jan

- Enrolled relatively ‘sick’ PE patients who were tachypneic, hypoxic, tachycardic, and had >70% thrombotic occlusion of lobar or main pulmonary arteries on CT

- Unfortunately this group did not fit the standard definition of submassive PE – that is, they didn’t look at RV dysfunction, elevated Trop or elevated BNP

- Intervention group got ‘half dose’ thrombolysis

- Primary outcome – long-term development of pulmonary hypertension, which was reduced significantly more in the half dose lytic group

- Long-term reduction in the incidence of pulmonary hypertension compared to anticoagulation alone was 57% vs 16%

- However, no mortality benefit and no significant difference in recurrent PE

- No difference in bleeding, but some argue that the bleeding rates were too low to detect a difference given the power of the study

PEITHO Trial Fibrinolysis for patients with Intermediate-Risk Pulmonary Embolism. NEJM, April 2014.

- Double-blind RCT >1000 pts compared full dose tenectaplase plus heparin vs placebo plus heparin for patients with RV dysfunction on Echo or CT as well as a positive Troponin

- Primary outcome – death or hemodynamic decompensation within 7 days

- No significant difference in mortality, but there was less hemodynamic instability in the lytic group

- Significant 4-5 fold increase in major hemorrhage (including ICH), especially in patients >75 years old

Conclusion: In patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism, fibrinolytic therapy prevented hemodynamic decompensation but increased the risk of major hemorrhage and stroke. Additional points:

- the more anatomically extensive the PE is on CT, the more likely lytics will be beneficial

- the shorter the duration of symptoms, the more likely lytics will be beneficial

Putting it all together in One Suggested Approach to consider: For patients under the age of 75, with absolutely NO contraindications to thrombolysis, with a fresh acute PE of just a few hours, that’s anatomically extensive on the CT, AND who fulfill the strict definition of submassive PE, because we know that half-dose lytic probably does NOT significantly increase the risk of major bleeding, and it may prevent pulmonary hypertension and may decrease the risk of cardiovascular instability, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to give half-dose lytic for submassive PE.

For a discussion and review of the RUSH protocol and POCUS in PE see Episode 18 – Point of Care Ultrasound Pearls & Pitfalls

Lisa Thurgur – Tales from the Poison Centre: Toxicology Update 2014

Naloxone

The goal of using naloxone is to restore normal ventilation, not to restore mental status or completely reverse opioids. Start with a dose of 0.01mg/kg in opiate patients, or 0.005mg/kg in patients with an unknown opiate history, titrating stepwise to respiratory rate. Patients in a coma often do not respond to

Acetominophen

Toxic ingestion dose is 150mg/kg.Time of ingestion is often unclear. Acetominophen overdose patients can present with altered LOC, when they are in severe overdose, and management is not just about NAC for these patients. Start with NAC – but call the poison centre, as it might not be enough in a massive overdose (>350-400mg/kg), and consider the following other adjunctive options:

1) Fomepizole – acetaminophen gets metabolized to NAPQI, increasingly in overdose, along the p450 system. CYP2E1 is actually inhibited by fomepizole, the production of NAPQI is theoretically halted by inhibiting the enzyme. (Study in rats only – decreased liver enzymes. Brennan Ann Emerg Med 94). Only give one dose, because repeat doses will turn up the enzyme.

2) Dialysis? Acetominophen is a water soluble, and not protein bound in large doses. If the patient has a massive ingestion, NAC may not be enough, so consult nephrology early.

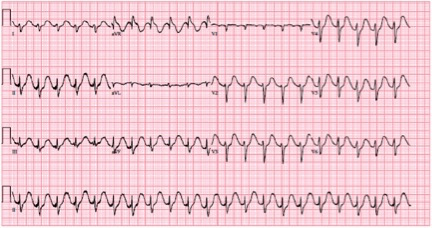

Sodium Channel Blocker Overdose

Tall R wave in aVR, wide QRS.

Think sodium channel blocker, perhaps TCA overdose.

When the patient subsequently seizes, the management begins of a presumed TCA overdose.

First – ABCS, low threshold for intubation, GI decontamination

Fluids for hypotension

Sodium Bicarb boluses for QRS >120 msec, or dysrhythmias,

Benzodiazepines for seizures

Fluids and vasopressors – for hypotension

Cooling for anticholinergic hyperthermia Physostigmine is contraindicated.

For a fantastic review on lipid emulsion therapy see Chris Nickson’s review on Life In the Fast Lane

Intralipid Therapy (Lipid Emulsion)

Intralipid has been shown to be an effective antidote to local anesthetic overdose in humans. Animal studies and case reviews of intralipid for lipophilic drugs overdoses. I.e. wellbutrin (Siriani paper) and lamotrigine are promising.

Drugs to consider Intralipid therapy in consultation with your poison control centre: TCAs, some BBlockers (propanolol), CCBs (verapamil), haloperidol, buproprion. How to do – Bolus 100mL, then hang the rest of the 500mL bag.

Do NOT administer intralipid before you would give all the other antidotes appropriate for the overdose. First address the ABCs, give supportive care, specific antidoes, and then intralipid as an adjunct. Remember that intralipid can interfere with other medications (i.e. can bind benzodiazepines you are giving for seizures).

For a fantastic review on lipid emulsion therapy see Chris Nickson’s review on Life In the Fast Lane

Buproprion (Wellbutrin) Abuse

Crushing and injecting Buproprion is associated with a crack or cocaine-like high. Beware of unexplained requests for Wellbutrin prescriptions – look for these skin findings:

ASA Toxicity

Any patient who presents with a suspected overdose with a resp rate >35 – think ASA until proven otherwise (just like low RR – think opioids).

Pitfalls: Always order serial q2h hour ASA levels as they may rise due to tablet concretions in the gut. Always add potassium when alkalinizing the urine. Remember to hyperventilate intubated patients. Get nephrology involved early, as delay in dialysis is the most common cause of premature death in an ASA overdose.

Hyperthermic Overdose Patients

Always take the hyperthermia seriously! The mortality rate for hyperthermic overdose patients is high (75%). Start aggressive cooling immediately, and contact the Poison Centre early.

Joel Yaphe – What Your Colleagues are Reading: Articles From 2013

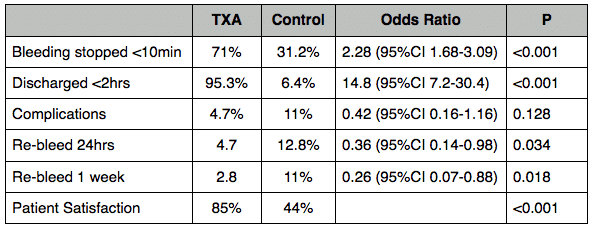

Tranexamic Acid for Epistaxis

A new and rapid method for epistaxis treatment using injectable form of tranexamic acid topically: a randomized controlled trial. Zahed R et al. Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Sep;31(9):1389-92

Objective: To compare topical tranexamic acid with anterior nasal packing in the treatment of anterior epistaxis

The Study: Randomized trial of 216 patients (out of 316 assessed for eligibility)

Inclusion: Patients randomly selected from those presenting with epistaxis to a single ED in Iran

Exlusion:

- shock

- major trauma

- posterior epistaxis

- coagulopathy/bleeding disorder

- visible bleedling vessel

Intervention Group: 15cm cotton pledget soaked in 500mg of the IV injectable form of tranexamic acid and lef in place until bleeding stopped. Rescue anterior pakcing was used if needed.

Standard Treatment Group: Topical Epi + Lidocaine for 10 minutes followed by tetracycline impregnated anterior packing, left in place for 3 days. Rescue cautery was used if needed.

Outcome:

Issues:

- The control arm may not have received optimal first line treatment (many can be treated with vasocontrictor and cautery; nasal tampons were not used)

- Did non control for or measure severity of bleeding

- Additional benefit in terms of eliminating revisit for packing removal

Take home: Topical TXA is easy, and effective for control of anterior epistaxis

Cost: based on prices at one large Canadian urban hospital

- TXA $9.50 for 1gm IV injectable

- Nasal tampon: $5.75

If you do not have access to the injectable form of tranexamic acid, alternatively you can take a single 500mg pill of Cyclokapron (TXA) and dissolve it in 10-15ml of water to make a slurry to apply to the nasal mucosa

Targeted Temperature Management after Cardiac Arrest (TTM Trial)

Targeted Temperature Management at 33 versus 36 degrees after cardiac arrest. Nielsen N et al (TTM Investigators) NEJM 2013 Nov 17.

Background: Therapeutic Hypothermia targeting temperate of of 32-34 degrees is recommended in resuscitation guidelines, but questions remain as to the importance of hypothermia itself as opposed to pervention of hyperthermia in post cardiac arrest patients.

The Study: TCT conducted in Europe & Australia, enrolled 950 unconcious (GCS<8) adults post out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with ROSC > 20 minutes

Exclusion:

- >240 minutes post ROSC

- unwitnessed asystolic arrest

- temp<30

- ICH/Stroke

Groups:

- Target temperature 33 degrees

- Target temperature 36 degrees

For 28hr followed by gradual rewarming at 0.5 degrees/hr

Outcome: Primary: All cause mortality – 50% vs 48% HR 1.06 (0.89-1.28) p=o.51 Secondary: Poor neurologic function (CPC 3-5, mRS 4-6) or death at 180 days – 54% vs 52% (RR 1.02 0.88-1.16 p=0.78)

Conclusions: “In unconscious survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest or presumed cardiac cause, hypothermia at a targeted temperature of 33 degrees did not confer a benefit as compared with targeted temperature of 36 debrees”

Questions & Issues: Outcomes in both groups were significantly better than those a decade ago. Are there some patients who may benefit from more intensive cooling? Are there harms of intensive cooling? As the authors noted, “none of the point estimates were in the direction of benefit” for the 33 degrees group.

Take Home Point:

- Avoid hyperthermia

- Actively cool to at least 36 degrees

see Ryan Radecki’s EM literature of note commentary of the TTM trial, and Scott Weingart’s commentary at EM Crit.

Concussions and their Consequences

Concussions and their consequences: current diagnosis management, and prevention. Tator CH. CMAJ 2013; 185(11):975-979

This review article is a handy aid for the practicing EM doc. As Dr. Tator writes, “it is now standard practice for every concussed person to be removed from active participation and to be evaluated by a medical doctor“. (This usually means you…….)

Diagnosis: Clinical see Sport Concussion Assessment Tool, 3rd ed (full pdf)

Protocol for Graduated return to play:

- No activity – complete cognitive and physical rest (24-48h)

- Light aerobic exercise (walking, swimming, stationary cycling)

- Sport specific exercise (no head impact activities)

- Noncontact training drills

- Full contact practice (only after physician re-examination)

- Return to play

- at least 24h between steps, and progression only after symptoms completely resolved

- slower progression in children and youth

For Concussion Guidelines for Physicians visit Parachute Canada

Clinical Decision Rule to Rule Out Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Clinical Decsion Rules to Rule out Subarachnoid Hemorrhage for Acute Headache. Perry, JJ et al. JAMA 2013;310:12:1248-1255 The Study – Multicentre cohort study at 10 Canadian Tertiary care hospital EDs to develop a clinical decision rule for detection of SAH

Inclusion Criteria

- adults >16y

- headache peaking within 1h

- no neurological deficits

- within 14d of onset

Exlusion

- trauma

- recurrent headaches

- brain tumors, previous aneurysm or SAH

SAH Definition

- Suarachnoid blood on CT

- Xanthachromic CSF

- Any RBC in the final tube of CSF and aneursym or AVM on cerebral angiography

Results – 2131 patients, 132 (6.2%) with SAH

Derived Decision Rule – investigate if any of:

- Age >40y

- Neck pain or stiffness

- witnessed LOC

- onset during exertion

- thunderclap headache

- limited flexion on exam

Sensitivity 100% (95%Cl 97.2%-100%) Specificity 15.3% (95%CL 13.8-67.9%) The problem:

- Specificity is poor

- Baseline investigation rate was 84.3%

- Investigation rate with decision rule would have been 85.7% (an increase in investigations including more LPs using the rule compared to baseline practice without the rule!)

Take Home: Not ready for prime time The authors note that implementation studies are required before the rule is employed in clinical care May be useful as teaching tool to learn some of the important features of SAH clinical assessment

Now Test Your Knowledge

Dr. Helman, Dr. Carr. Dr. Yaphe and Dr. Thurgur have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Key References

Paxton J , J Trauma. 2009 Sep;67(3):606-11. Proximal humerus intraosseous infusion: a preferred emergency venous access. Abstact

A Comparison of Albumin and Saline for Fluid Resuscitation in the Intensive Care Unit. The SAFE Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2247-56 Full PDF

Backer, D. Comparison of Dopamine and Norepinephrine in the Treatment of Shock. N Engl J Med 2010;362.779-889 Full PDF

Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Heusel G, Heinrich F, Kasper W; Management Strategies and Prognosis of Pulmonary Embolism-3 Trial (MAPPET-3) Investigators. Heparin plus alteplase compared with heparin alone in patients with submassive pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2002 Oct 10;347(15):1143-50. PubMed PMID: 12374874. Free Full Text

Sharifi M, Bay C, Skrocki L, Rahimi F, Mehdipour M; “MOPETT” Investigators. Moderate pulmonary embolism treated with thrombolysis (from the “MOPETT” Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2013 Jan 15;111(2):273-7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.09.027. Epub 2012 Oct 24. PubMed PMID: 23102885. Free Full Text

Meyer G et al. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1402-1411, April 10, 2014DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302097. Free Preview

Zahed, R. A new and rapid method for epistaxis treatment using injectable form of tranexamic acid topically: a randomized controlled trial Am J Emerg Med. 2013 Sep;31(9):1389-92. Abstract

Thank you so much for putting the time and effort into this. You are adding knowledge to the international medical community, and that is a noble good.

[…] in Canada, Anton Helman and the Emergency MEdicine Cases crew range far and wide in Episode 44 – Whistler’s Update in Emergency Medicine Conference 2014 Highlights. Topics include TTM, tranexamic acid for epistaxis, approaches to shock including the RUSH […]