Dr. Andrew Worster and the BEEM (Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine) group from McMaster University has teamed up with EM Cases, Justin Morgenstern (@First10EM) and Rory Spiegel (@EMNerd_) to bring you a blog that blends the BEEM critical appraisals in a case-based, interactive, practice-changing format. In each post we choose the most important literature on a given topic and run through a case, learning how to apply evidence based medicine to our practice. Welcome to BEEM Cases!

And here’s BEEM Cases 1 – Pediatric Minor Head Injury…

Written by Justin Morgenstern (@First10EM), edited by Anton Helman (@EMCases), adapted from the BEEM Course, Jan 2016

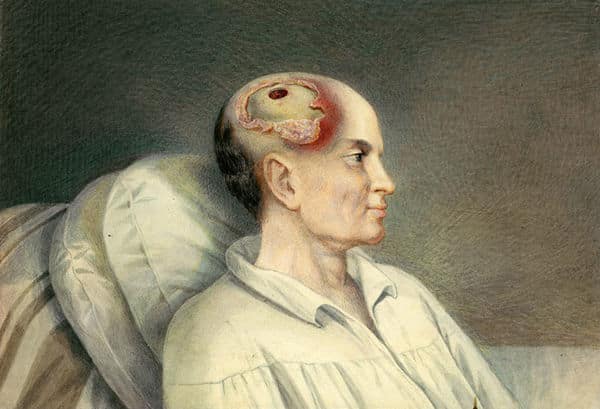

Pediatric Minor Head Injury – Decision Rules, Isolated LOC & Strict Rest

The Case…

With seconds left in the game, Melissa, an 11 year old girl, drives hard to the basket for a layup. She gets knocked to the ground, and doesn’t see the winning shot pass through the net, because it appeared as though she briefly lost consciousness. She quickly gets back up and celebrates with her friends, but after the celebrations, her parents bring her to your community emergency department to get checked. You confirm that she did indeed briefly lose consciousness. She complains of a mild ongoing headache as well as nausea. Her neurologic exam is normal and she has no signs of skull fracture.

You don’t need stats to know that pediatric minor head injury is common. Kids love to run around knock their heads into things. Luckily, serious traumatic brain injury is relatively rare. Most children we see in the ED after minor head injuries are awake, acting normally, and have a very low risk of an intracranial bleed. Our main job is balancing the small risk of serious brain injury with the potential harms of CT scanning.

Question #1

Which previously established decision rule for identifying children requiring a CT scan post-head injury has the best diagnostic accuracy?

Question #2

In children with minor head injuries, does isolated loss of consciousness predict clinically-important traumatic brain injury?

Question #3

Is there benefit to recommending strict rest after a child has a concussion?

Question #1 Discussion: The Best Decision Rule for Pediatric Head Injury?

Which previously established decision rule for identifying children requiring a CT scan post-head injury has the best diagnostic accuracy?

The Paper

Easter JS, Bakes K, Dhaliwal J, Miller M, Caruso E, Haukoos JS. Comparison of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE Rules for Children With Minor Head Injury: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med. 2014 Aug;64(2):145-52. PMID: 24635987

Study details (PICO)

| Population | Children ( |

| Intervention | The PECARN, CATCH and CHALICE rules |

| Comparison | Physician judgement |

| Outcomes | Clinically important traumatic brain injury |

| Study type | Prospective cohort study |

Key results

Among the 1,009 children, 21 (2% [95% CI: 1%, 3%) had clinically important traumatic brain injuries. Only physician practice and PECARN identified all clinically important traumatic brain injuries.

- PECARN

- Sensitivity = 100% [95% CI: 84, 100]

- Specificity = 62% [95% CI: 59, 66]

- LR + 2.7 [95% CI: 2.5, 2.9]

- LR – 0 [95% CI: 0, ?]

- CATCH

- Sensitivity = 91% [95% CI: 70, 99]

- Specificity = 44% [95% CI: 41, 47]

- LR + 1.6 [95% CI: 1.4, 1.9]

- LR – 0.2 [95% CI: 0.1, 0.8]

- CHALICE

- Sensitivity = 84% [95% CI: 60, 97]

- Specificity = 85% [95% CI: 82, 87]

- LR + 5.5 [95% CI: 4.3, 7.1]

- LR – 0.2 [95% CI: 0.1, 0.5]

- Physician practice

- Sensitivity = 100% [95% CI: 84, 100]

- Specificity = 50% [95% CI: 47, 53]

- LR + 2.0 [95% CI: 1.9, 2.1]

- LR – 0 [95% CI: 0, ?]

BEEM critique

This is a well-designed study trying to answer an important question in pediatric emergency care. The primary outcome is relevant to patients. The execution of the study design was well done. There was overall good follow-up of patients (90%) and the researchers were careful to try to catch all patients with clinically important injury.

There were some limitations of the study design. Firstly, the sample size for clinical decision rule studies is typically based on the number of outcomes needed and this was not the case for this study, hence the number of patients with significant injury was only 21. This limited number results in the wider confidence intervals seen around point estimates. Secondly, the inter-rater reliability during data collection was only moderate.

The Bottom line for the best CDR

Based on this study, it appears that both clinician gestalt and the PECARN Rule have adequate sensitivity to rule out important injuries at the bedside, with the PECARN rule being slightly more specific than gestalt. Clinicians should be aware that this conclusion is somewhat limited by the wide confidence intervals in is study, and that clinical expertise and shared decision making remain important components of safe discharge of these patients.

Link to The PECARN rule on MDcalc

Case continued…

You review the PECARN criteria with Melissa and her parents. The clinical decision tool indicates that she has less than a 0.05% chance of clinically important traumatic brain injury. You suggest forgoing the CT, but Melissa’s parents seem concerned. “Melissa passed out! I googled it, and it says right here that if you pass out you could die, and you really need to get a scan of your head to be safe.“

Question #2 Discussion: Isolated Loss of Conciousness in Pediatric Minor Head Injury

In children with minor head injuries, does isolated loss of consciousness predict clinically-important traumatic brain injury?

The Paper

Lee LK, Monroe D, Bachman MC, Glass TF, Mahajan PV, Cooper A, , Stanley RM, Miskin M, et al. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Working Group of Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Isolated loss of consciousness in children with minor blunt head trauma. JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Sep;168(9):837-43. PMID: 25003654

Study details

| Population | Children ( |

| Clinical finding | Isolated loss of consciousness |

| Comparison | Loss of consciousness in conjunction with other symptoms |

| Outcomes | Clinically important traumatic brain injury (ciTBI); traumatic brain injury on CT |

| Study type | Secondary analysis of a prospective observational cohort |

Key results

The primary focus examined children with LOC but no other PECARN predictors of head injury. There were 2780 PECARN-isolated LOC patients of which 38 (1.9% [95% CI: 1.4, 2.6]) had a TBI on CT and 13 (0.5% [95% CI: 0.2, 0.8]) had a clinically important TBI (ciTBI). This was significantly lower than the patients who had additional PECARN ciTBI predictors.

The secondary focus examined children with LOC but no other clinical predictor found in a pediatric TBI study (expanded-isolated LOC). Of the 576 patients in this group, only one (0.2% [95% CI: 0.0, 1.0]) had a clinically important TBI. Of the 326 patients in this group who had a CT scan, three had TBI noted (0.9% [95% CI: 0.2, 2.7]).

BEEM critique

The number of patients in this study is impressive and the value of this is seen in the narrow confidence intervals around the summary estimates. It is unlikely that a primary cohort study of this magnitude will ever be conducted to specifically answer this question, and so this might continue to be the best evidence that emergency physicians ever have.

This is a secondary analysis of the data from the Kuppermann (2009) study that established the PECARN head-injury rule for children. The methodology of the original study, and therefore this study, is robust. Follow-up, although not specified in this paper, is described in the original paper and included ensuring that patients who were sent home were followed up by phone. Those not reached by phone were searched for to ensure they did not re-present to a healthcare facility or the morgue.

The Bottom line for isolated loss of consciousness in Pediatric Minor Head Injury

The results of this study indicate that the child with a head injury who has isolated LOC and no other concerning history, signs or symptoms of injury is at extremely low risk of clinically-important injury and can safely be sent home in the charge of reliable caregivers with appropriate instructions. Periods of observation in the ED are valuable and appropriate in place of head CT if there are concerns.

Case Continued…

You explain to the parents that there is a very low chance of significant traumatic brain injury. After a shared decision making conversation, you decide to opt for a brief period of observation instead of a CT scan. After a period of observation, Melissa’s neurologic exam is repeated and is normal. She is feeling better, although she does have a mild ongoing headache, noise sensitivity, and some mild nausea. You are ready to discharge the patient when your medical student turns to you and says, “Couldn’t this be a concussion? Shouldn’t she be put on strict bed rest for a few days?”

Question #3 Discussion: Strict Bed Rest?

Is there benefit to recommending strict rest after a child has a concussion?

The Paper

Thomas DG, Apps JN, Hoffmann RG, McCrea M, Hammeke T. Benefits of strict rest after acute concussion: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015 Feb;135(2):213-23. PMID: 25560444

Study details (PICO)

| Population | Patients aged 11 to 22 years old presenting to the ED with acute ( Excluded: Unable to speak English; couldn’t consent; pre-existing intellectual disability or mental health issue; previously diagnosed intracranial injury; being admitted; lived >one hour from the investigation center or at the discretion of the recruiting physician |

| Intervention | Strict rest at home for five days (no school, work or activity) followed by stepwise return to activity |

| Comparison | Usual care (one to two days’ rest) followed by stepwise return to activity |

| Outcomes | Compliance with physical and mental activity recommendations; symptoms; neurocognitive performance (ImPACT); balance |

| Study type | Randomized, controlled trial |

Key results

Both groups (n=50 and 49) reported an approximate 20% decrease in physical activity and energy expenditure for the five days post-injury. There was more reported high and moderate mental activity on days two to five in the usual care group (8.33 vs. 4.86 hours, P=0.03).

67% of patients in the usual care group experienced symptom resolution during follow-up compared to 63% in the strict group (P=0.82). It took three days longer for 50% of patients in the strict group to report symptom resolution. The strict group had more post-concussive symptoms compared to the usual care group over the 10-day follow-up period (70.4 vs. 50.2, P<0.03).

There were no significant differences noted in computer-based neurocognitive tests and balance scores noted and no significant differences in neuropsychological assessments except for the Symbol Digit Modalities Test for which the usual group performed worse at day three and better at day 10.

BEEM critique

This is a novel, single-center study examining a topic that we often struggle with in the ED: How long to keep someone resting post-concussion. The patients were aged 11 to 22 years, and so it is questionable whether this study can be generalized to younger pediatric patients. The two groups did differ significantly in terms of age with the strict rest group being older. The impact of this difference is unknown. Blinding of the subjects was not possible. The outcome measures such as re-presentation to ED and proportion of patients with symptoms beyond 10 days were not described; 11% of patients were lost to follow-up.

The Bottom line for strict bed rest

This study has opened the door to a very interesting line of inquiry, and further research will be very useful. For the time being, however, there is evidence to support a two-day rest period following a concussion with a gradual return to activity. Keeping a child at strict rest for five days post-concussion appears to offer no benefit, and there is evidence of harm from this strategy.

Case resolution…

Melissa is sent home with a graduated return to play plan and return precautions. She returns to the department a week later, but this time because her brother has a buckle fracture of his distal radius. Melissa is pleased to tell you she is feeling great and was named team MVP after her game winning bucket.

For our main episode podcast on Pediatric Head Injury where we discuss both minor and major head injury management in children go to Episode 3 – Pediatric Head Injury

For our chapter on Pediatric Head Injury download our FOAMed interactive ebook EM Cases Digest Vol. 1 MSK & Trauma HERE

References

Easter JS, Bakes K, Dhaliwal J, Miller M, Caruso E, Haukoos JS. Comparison of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE Rules for Children With Minor Head Injury: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med. 2014 Aug;64(2):145-52. PMID: 24635987

Lee LK, Monroe D, Bachman MC, Glass TF, Mahajan PV, Cooper A, , Stanley RM, Miskin M, et al. Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Working Group of Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). Isolated loss of consciousness in children with minor blunt head trauma. JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Sep;168(9):837-43. PMID: 25003654

Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet (London, England). 374(9696):1160-70. 2009. PMID: 19758692

Thomas DG, Apps JN, Hoffmann RG, McCrea M, Hammeke T. Benefits of strict rest after acute concussion: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015 Feb;135(2):213-23. PMID: 25560444

Other FOAMed Resources for Pediatric Minor Head Injury

CanadiEM & BoringEM SLucket & Teresa Chan dissect the JAMA paper on isolated loss of conciousness on CandiEM

Andrew Sloas talks Pediatric Concussion on his PEMED podcast

Dr. Helman & Dr. Morgenstern have no conflicts of interest to declare

For more EM Cases content on Pediatric Emergencies check out our free interactive eBook,

EM Cases Digest Vol. 2 Pediatric Emergencies here.

I am curious how it was calculated to be less than 0.05% risk of TBI for the 11 year old with head injury and LOC. By my interpretation of the PECARN guidelines this child would have a 0.8% risk of clinically important TBI. and in this situation observation vs CT should be considered as opposed to sending the child home. Even based off the Lee study 1.9% of patients with isolated LOC had TBI. Could you please explain? Thanks!