Just as pediatric patients are not small adults, geriatric patients are not just old adults. Here are a few facts: the oldest old are the fastest growing population in North America. Older adults with severe injuries represent at least 40% of all adults with severe injuries in the Canadian trauma system. Older patients are more likely to experience trauma and to have worse outcomes after a trauma. In this Part 1 of our 2-part EM Cases podcast series on Geriatric Trauma, Dr. Barbara Haas, Dr. Camilla Wong and Dr. Bourke Tillmann answer questions such as: why are older patients under-triaged to trauma centers and how does that affect outcomes? What is the utility of the Shock Index in older patients? How should we adjust airway management for the older trauma patient? Which older patients do not require head or c-spine imaging after a ground level fall? Why is it challenging, yet of utmost importance, to clear the c-spine of a geriatric trauma patient as soon as possible? When can anticoagulation medications be safely resumed after an older person has sustained a minor head injury? and many more…

Podcast production, sound design & editing by Anton Helman. Voice editing by Danielle Lewis.

Preproduction by Anh Thi Nyugen, Barbara Haas, Camilla Wong & Anton Helman.

Written Summary and blog post by Winny Li, edited by Anton Helman August, 2021.

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A. Wong, C. Haas, B. Tillmann, B. Geriatric Trauma Part 1: The Under-Triaging Problem, Resuscitation, Airway, Head and C-spine Imaging, Clearing the C-spine. Emergency Medicine Cases. August, 2021. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/geriatric-trauma-under-triaging-resuscitation-airway-head-c-spine-imaging-clearing-c-spine. Accessed [date]

The problem of under-triaging geriatric trauma patients

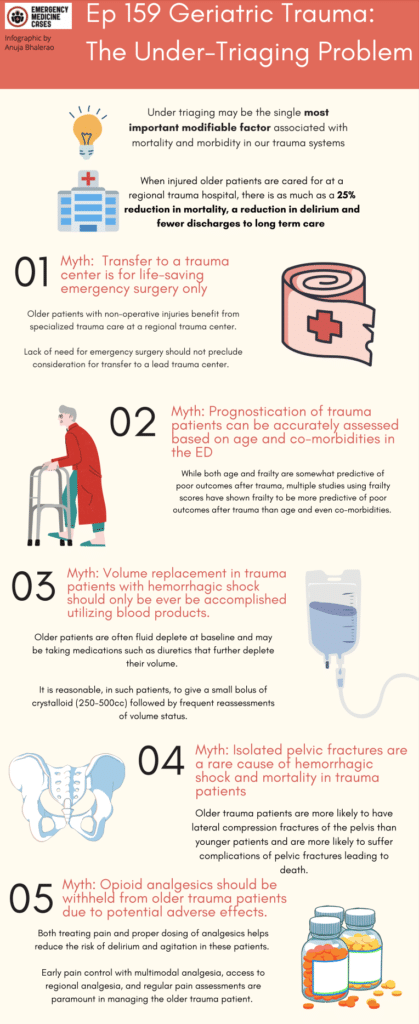

Undertriage, both at the ED triage and to the lead trauma center, may be the single most important modifiable problem in trauma in older adults. In Ontario, >2/3 of older adults with major traumatic injuries (often related to minor mechanisms of injury such as ground-level falls) are triaged to a non-trauma center and <50% of these patients are transferred to a trauma center. Observational studies suggest as much as a 25% reduction in mortality, a reduction in delirium (51 vs 41%, P = 0.05) and fewer discharges to long term care (6.5% vs 1.7%, P=.03) when injured older patients are cared for at a lead trauma hospital. Trauma centers not only provide definitive surgical care, but they improve mortality and functional outcomes through access to multidisciplinary teams specialized in trauma care. Older patients with non-operative injuries also benefit from care at a lead trauma center. The lack of need for emergency surgery should not preclude consideration for transfer to a lead trauma center. Ground-level falls are are the most common mechanism of injury in older patients and carry a 10-fold higher mortality rate in older patients.

What can we do as emergency physicians to mitigate undertriage of older trauma patients? Be an advocate for your older trauma patients even if they have non-operative injuries, be familiar with your local trauma transfer guidelines (see below for example) and maintain a low threshold to transfer older trauma patients to a lead trauma center.

The lack of need for emergency surgery should not preclude consideration for transfer to a lead trauma center.

Example of trauma center activation guidelines for educational purposes only. Note that patients age >55 are considered high risk which “may warrant transfer to lead trauma center at a lower threshold”

Anatomic and physiologic considerations in geriatric trauma care

- Comorbid disease, medications and frailty may all affect the expected physiologic presentation of trauma in older people

- Multiple studies have shown frailty to be more predictive of poor outcomes than age after trauma

- Consider removal from backboard ASAP, measures to prevent hypothermia, being vigilant in maintaining c-spine precautions, more frequent assessments, acting on small changes in vital signs more readily, binding the pelvis early and placing an arterial line early

Hemodynamic considerations, the utility of the Age Shock Index (ASI) and fluid resuscitation

Normal vital signs in the elderly patient should not be considered as reassuring as they might be in younger patients. It is more challenging to recognize the early symptoms of shock in older patients owing to diminished physiologic reserve, chronic diseases that impair their ability to respond to injury, medications for cardiac conditions, e.g. antihypertensives, β-blockers, all of which may blunt a physiologic tachycardic response to stress or hemorrhage.

Concerning vitals in the geriatric trauma population:

- sBP <110 or sBP 40 less than baseline

- HR > 90

- RR < 10

Use Age-adjusted Shock Index (age x HR/SBP ) to augment (but not replace) clinical suspicion. It alone is not sensitive enough to rule out serious injury.

If age-adjusted shock index > 50: suspect shock or occult shock

Pitfall: A negative Age Shock Index should not be used as a rule out for significant injury

Other hemodynamic considerations include narrow window of normal volume status (patients are often volume deplete, however they are more sensitive to fluid overload). Be judicious with fluid resuscitation, use PoCUS as a tool to guide resuscitation and consider placement of an arterial line. While blood products are generally favoured over crystalloid in the hypotensive young trauma patient, our elderly trauma patients are often fluid deplete at baseline and may be on diuretics that further worsen their volume status. In the elderly trauma patient, it is reasonable to give a small bolus of crystalloid (250-500cc) and reassess their volume status during the initial resuscitation.

Pitfall: A common pitfall is to be dogmatic about volume resuscitation only with blood products in all trauma patients suspected of hemorrhagic shock. Do not dismiss crystalloids in geriatric trauma patients the way you might in younger patients; many older trauma patients are volume depleted at baseline.

Airway considerations in the geriatric trauma patient

Older patients often have multiple predictors of a difficult anatomic (dentures, restricted mouth opening, c-collar) and physiologic (low pulmonary reserve, underlying disease etc) airway . Endotracheal intubation carries a higher risk of complications in older patients such that the pros and cons should be carefully considered.

- Preoxygenation

- Lower physiologic pulmonary reserve, pre-oxygenate fully whenever possible

- Do a finger sweep to feel for dislodged dentures

- Dentures provide an excellent scaffold during pre-oxygenation/BVM, but may inhibit laryngoscopy; the timing of denture removal just prior to laryngoscopy when making the switch from BVM to ETT is important

- Airway equipment

- Consider hyperangulated videolaryngoscope + adjunct (bougie in all but grade 3b and 4 airways) given reduced c-spine and jaw mobility

- RSI medications dose adjustments

- Given higher risk of hypotension and slower distribution time, reduce dosages of induction agent (3/4 to ½ usual adult dose)

- Use higher dose of paralytic (eg. rocuronium 1.2mg/kg)

Neurologic considerations in the geriatric trauma patient

- Cognitive impairment and/or prior CVA may preclude a reliable assessment

- Older patients often demonstrate delayed neurologic signs of significant intracranial pathology due to cerebral atrophy

Pitfall: undertreating and overdosing analgesics in older trauma patients is a common pitfall. Both treating pain and proper dosing that is lower than ‘standard’ adult dosing of analgesics helps reduce the risk of delirium and agitation in these patients.

Common injury patterns in the geriatric trauma patient

Falls: head, spinal column, chest and pelvic injuries

Older people with low mechanism falls are more like to sustain a head injury and chest injury (rather than FOOSH pattern injury, especially if they have consumed alcohol) and have associated spinal column bony or cord injuries. They are also more likely to suffer lateral compression fractures of the pelvis and more pelvic bleeding requiring transfusion and angiography.

MVC: spinal column, chest and aortic injuries

Seat-belt induced thoracic and aortic trauma at low speeds are more common. Also be vigilant of hyperextension injuries of the neck and chest injuries (including rib and clavicle fractures) which are associated with high mortality in the older trauma patient.

Ep 160: Geriatric Trauma part 2

Geriatric trauma workup

Lactate and base deficit (BD)

Both serum lactate and base deficit are important biomarkers for shock and occult shock and should be considered predictors of serious or severe injury in geriatric trauma patients, even when physical examination is unrevealing. Serum lactate (>2) or base deficit (<-6) are associated with major injury and mortality in trauma patients and may be present even in older trauma patients with normal/near normal vital signs and low impact injury (eg. ground-level fall).

Pearl: consider a lower threshold to obtain a serum lactate and base deficit in older trauma patients to help discover occult hemorrhagic shock

Head and C-spine imaging

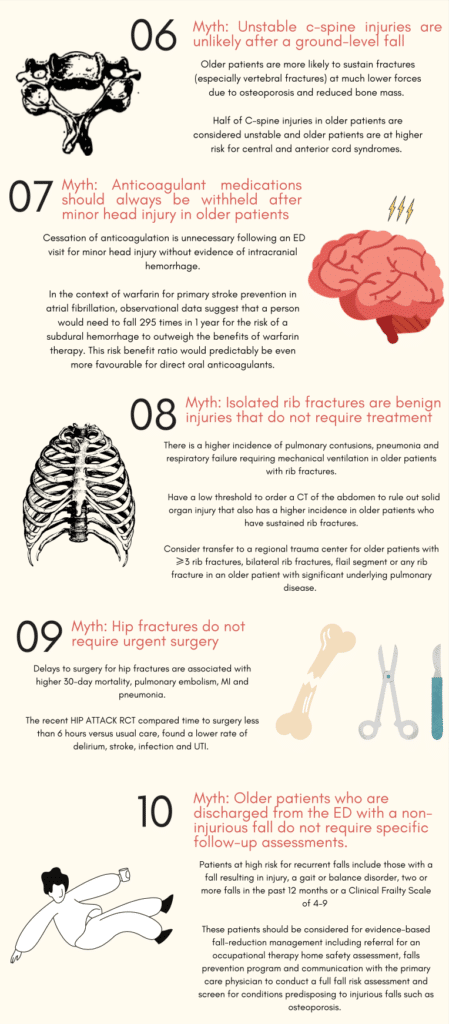

Osteoporosis and overall reduced bone mass mean older patients are more likely to sustain fractures (especially of the spinal column) at much lower forces. 50% of C-spine injuries in geriatric patients are unstable. Older patients are at higher risk for central and anterior cord syndromes. Our experts recommend that any geriatric trauma patient who is undergoing a head CT for trauma should also undergo cervical spine imaging.

Which geriatric trauma patients do not need c-spine imaging?

The Canadian C-spine Rule studies excluded patients >65 years of age. While the NEXUS criteria for c-spine imaging found a 100% sensitivity for clinically significant c-spine injury in a subgroup analysis of older patients, this has not been validated. Our experts recommend that for those who are ambulatory, do not meet high risk criteria of the Canadian C-Spine rule, have no signs of trauma above the clavicle, and on reliable examination have no c-spine tenderness or paresthesias, c-spine imaging may be deferred.

Clearing the c-spine in geriatric trauma patients

There are significant patient harms associated with delayed c-spine clearance including pressure ulcers, dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia, respiratory failure, agitation, and delirium. The goal at each center should be to have processes in place to quickly evaluate and clear the c-spine. There is literature suggesting that MRI to evaluate for occult c-spine injury in blunt trauma can change management up to 6% of the time. However, other data suggest that the incidence of occult c-spine injuries in this setting is as low as 0.12%. The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma guidelines recommends that in the obtunded adult blunt trauma patient, a cervical collar can be safely removed after a negative high-quality CT scan result alone. If patients have an abnormal CT c-spine or it is difficult to obtain a reliable clinical exam due to underlying cognitive impairment, our experts recommend an MRI to evaluate for occult c-spine injury. Depending on your location of practice and accessibility to MRI imaging, transfer to a lead trauma hospital may be warranted to facilitate urgent imaging.

Resuming anticoagulation after minor head injury in the geriatric trauma patient

Literature suggests that cessation of anticoagulation is unnecessary following an ED visit for head injury if imaging is not indicated or if imaging rules out a bleed. Specifically in the context of warfarin for primary stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation, a person must fall about 295 times in 1 year for the risk of a subdural hemorrhage to outweigh the benefits of warfarin therapy. This risk benefit ratio would predictably be even more favourable for direct oral anticoagulants since direct oral anticoagulants have been shown to have a lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage than warfarin. While the risk of bleeding may not be modifiable, our experts stress the importance of identifying modifiable risk factors that contribute to falls in the elderly (vestibular disorder/poor balance, Vitamin D insufficiency, medications linked to falls, postural hypotension, vision impairment, home hazards), and having a low threshold to provide occupational therapy in the home for fall prevention.

Take home points for geriatric trauma part 1

- Maintain a low threshold to transfer elderly trauma patients to a lead trauma hospital

- Occult shock can be difficult to identify in the elderly; use the Age Shock Index, lactate, and base deficit to complement your clinical assessment

- Older trauma patients are often volume deplete at baseline; consider 250-500cc crystalloid bolus in the initial resuscitation

- Older trauma patients need optimized pre-oxygenation due to lower pulmonary reserve

- Dentures in for BVM, remove just before laryngoscopy

- Avoid the common pitfall of undertreating pain in the older trauma patient

- Lower analgesic and induction agent dose, but higher paralytic dose

- Lower threshold to perform c-spine imaging, especially if obtaining CT head

- Clearing c-spine urgently is of high importance; if unable to clear in timely manner or lack of advanced imaging, consider transfer to a lead trauma hospital

- Anticoagulation in the setting of CT-negative head trauma – do not need to withhold anticoagulants, but do identify and manage modifiable risk factors for falls

References

- American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. “ACS TQIP geriatric trauma management guidelines.” (2015): 3-26. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqp/center-programs/tqip/best-practice

- Calland JF, Ingraham AM, Martin N, et al. Evaluation and management of geriatric trauma: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(5 Suppl 4):S345-S350.

- Arslan B. Geriatric trauma. In: Karcioglu O, Topacoglu H, eds. Trauma Surgery. InTech; 2018.

- Lenartowicz M, Parkovnick M, McFarlan A, Haas B, Straus SE, Nathens AB, Wong CL. An evaluation of a proactive geriatric trauma consultation service. Ann Surg. 2012 Dec;256(6):1098-101.

- Nakamura Y, Daya M, Bulger EM, et al. Evaluating age in the field triage of injured persons. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(3):335-345.

- Poulton A, Shaw JF, Nguyen F, Wong C, Lampron J, Tran A, Lalu MM, McIsaac DI. The Association of Frailty With Adverse Outcomes After Multisystem Trauma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2020 Jun;130(6):1482-1492.

- Min L, Burruss S, Morley E, et al. A simple clinical risk nomogram to predict mortality-associated geriatric complications in severely injured geriatric patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(4):1125-1132.

- Cheung A, Haas B, Ringer TJ, McFarlan A, Wong CL. Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale: Does It Predict Adverse Outcomes among Geriatric Trauma Patients? J Am Coll Surg. 2017 Nov;225(5):658-665.e3.

- Frances Rickard, Sarah Ibitoye, Helen Deakin, Benjamin Walton, Julian Thompson, David Shipway, Philip Braude, The Clinical Frailty Scale predicts adverse outcome in older people admitted to a UK major trauma centre, Age and Ageing, Volume 50, Issue 3, May 2021, Pages 891-897.

- Clare D, Zink KL. Geriatric trauma. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2021;39(2):257-271.

- Hu KM, Brown RM. Resuscitation of the critically ill older adult. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2021;39(2):273-286.

- Lenartowicz M, Parkovnick M, McFarlan A, Haas B, Straus SE, Nathens AB, Wong CL. An evaluation of a proactive geriatric trauma consultation service. Ann Surg. 2012 Dec;256(6):1098-101.

- Kim, S. Y., Hong, K. J., Shin, S. D., Ro, Y. S., Ahn, K. O., Kim, Y. J., & Lee, E. J. (2016). Validation of the shock index, modified shock index, and age shock index for predicting mortality of geriatric trauma patients in emergency departments. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 31(12), 2016.

- Stiell, I. G. (2001). The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA, 286(15), 1841.

- Validity of a set of clinical criteria to rule out injury to the cervical spine in patients with blunt trauma. (2001). The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 19(5), 449-450.

- Schoenfeld AJ, Bono CM, McGuire KJ, et al. Computed tomography alone versus computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the identification of occult injuries to the cervical spine: a meta-analysis. J Trauma 2010;68(1): 109–14.

- Malhotra A, Wu X, Kalra VB, et al. Utility of MRI for cervical spine clearance after blunt traumatic injury: a meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2017;27(3):1148–60.

- Man-Son-Hing, M., Nichol, G., Lau, A., & Laupacis, A. (1999). Choosing Antithrombotic therapy for elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who are at risk for falls. Archives of Internal Medicine, 159(7), 677.

Drs. Helman, Haas, Tillmann and Wong have no conflicts of interest to declare

Fabulous episode. So good. Thanks.

This was a great segment. All the speakers were solid. I appreciated the delicacy of clearing the geriatric spine with either dementia or altered mentation. I would suggest a careful conversation with the NOK about goals of care. “Your mother had a fall. She is 90. I appreciate you want major injuries cared for and she needs 24 hour a day assistance already. Her CT neck is not perfect, but there is no clear abnormality. There is a very small chance the CT might miss an injury. In an ideal world, we would do an MRI, but that’s going to involve her remaining in the spine collar which is not ideal, being in a loud machine for a long time under sedation or on a ventilator – all of which is not ideal. How do you feel about that? When I put my hand on her neck and feel all the bones she does not have pain. I’m not going to discharge her, and we can also serially examine her in hospital and see how she does.” My point is I would shudder at the thought of calling a spine surgeon or trauma center for a 90 YO after a fall to ask for a transfer for an MRI under anesthesia, or to suggest this to my inpatient admitting doctors. I just don’t see them agreeing to it.