In this early release first podcast in a series of main episodes on COVID-19, Infectious Diseases specialist at Mount Sinai Health Systems and University Health Network and Professor at the University of Toronto Andrew Morris joins Anton on the latest on emergency screening, diagnosis and management of COVID-19, with some tips on managing yourself and your team by Howard Ovens…

Podcast production, sound design & editing by Anton Helman

Written Summary and blog post by Anton Helman March 20th, 2020

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A. Morris, A. Ep 137 COVID-19 – Screening, Diagnosis and Management. Emergency Medicine Cases. March, 2020. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/covid-19-screening-management-surge-capacity-airway-epidemiology. Accessed [date]

This podcast was recorded on March 19th, 2020 and the information within is accurate up to this date only, as the COVID pandemic evolves and new data emerges. The blog post will be updated regularly and we are working on a weekly update via the EM Cases Newsletter which will be replicated on the EM Cases website under ‘COVID-19’ in the navigation bar.

This podcast and blog post are based on Level C evidence – consensus and expert opinion. Examples of protocols, checklists and algorithms are for educational purposes only and require modification for your particular needs as well as approval by your hospital before use in clinical practice.

Quick tips on managing yourself and your team during the COVID -19 outbreak with Howard Ovens

- Communication amongst your ED group is crucial which can be augmented using available apps such as WhatsApp, Slack etc.

- Decide on reliable sources of information personally and amongst your group as there is an overwhelming amount of both reliable and unreliable information being disseminated

- Risk to health care workers may be overstated, and in many cases of “superspreader” events there were violations of personal protection guidelines, highlighting the importance of complying with guidelines

- Pace yourself – plan for rest, regular exercise, healthy food, sleep and maintain meditation if you are skilled

- Contributing in a constructive way to your ED group and your community may help alleviate anxiety around COVID-19

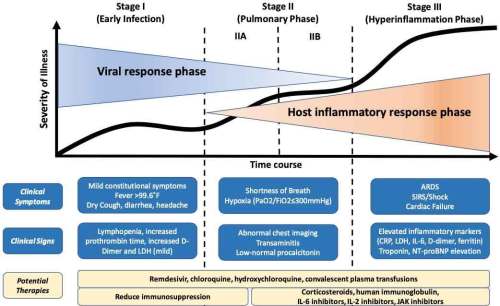

Clinical Presentation and natural history of COVID-19

There is much overlap in the presentation of COVID-19 with influenza, the common cold and bacterial pneumonia.

The typical triad includes dry/nonproductive cough, fever and shortness of breath, and most patients will have either fever, cough or both. However up to 20% of patients may have sore throat, nasal congestion or headache, and they may develop sputum production and others may experience antecedent gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea/vomiting and diarrhea in 3-10% of cases. Fever is present in only 44% of patients at the time of admission.

Most patients present within the first week, with a median incubation period of 4-5 days following exposure, with some cases having an incubation period of 14 days, or rarely longer.

Older patients and those with chronic medical conditions may be at higher risk for severe illness, however most cases are in people 30-69 years of age.

A small minority of patients develop septic shock and/or ARDS, which often occurs precipitously around 1 week after symptom onset. Therefore, patients who are discharged from the ED should be instructed to return for worsening shortness of breath or lethargy. Possible risk factors for progressing to severe illness may include older age and co-morbidities (lung disease, cancer, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, liver disease, diabetes, immunocompromising conditions).

From PulmCrit

The only sign or symptom that seems to have any predictive value for severe disease is shortness of breath.

Influenza co-infection is possible, however the incidence of influenza is decreasing and is likely to decrease further with wide spread social distancing. In one study 22% of 562 patients were positive for other viruses such as influenza, and a small minority of patients have been reported to develop bacterial pneumonia. However, most patients who are admitted to hospital with presumed COVID-19 are being given antibiotics on speculation, which may mask or prevent a secondary bacterial pneumonia.

The virus is present in respiratory specimens up to 22 days after illness onset and in stool specimens up to 30 days after illness onset and the WHO emphasizes isolation for 2 weeks after symptoms stop.

While transmission of virus is thought to occur via droplet from coughing, sneezing and talking, asymptomatic or subclinical infection based on positive swab results have been reported, which is one of the reasons that community spread has occurred so readily.

Reinfection with COVID-19 is unlikely as the virus has little diversity globally and most patients have a robust immune response to it suggesting that there would be immunity once infected. However if the virus mutates like the influenza virus does than any further immunity would at best be partial.

Update March 23, 2020: Diagnosis hasn’t changed substantially, other than recognizing that a) travel history is now totally irrelevant, and b) we anticipate nosocomial spread to arrive soon in Canada, so should consider COVID infection in hospital-acquired illness.

Update March 23, 2020: There is lots of talk about increased mortality with high BMIs, but the quality of evidence is sorely lacking at present.

Screening for COVID-19

Given the nonspecific presentation and current epidemiology (community spread, more common than all other respiratory illnesses), all patients who present with a respiratory illness should presumed to have COVID-19 until proven otherwise.

There has been no country that has been able to contain COVID-19, and so attention has turned to “flattening the curve” or slowing down the spread of COVID-19 by widespread screening early in the illness course, social distancing and isolating patients with any symptoms of COVID-19. However, few jurisdictions in North America and Europe have the infrastructure for mass screening and resources (testing kits, staff to perform the screening, contact tracing abilities, and lab capacity) and have been overwhelmed.

At present there is not enough epidemiological data to determine the accuracy/predictive value of the PCR viral swab for COVID-19, however the specificity is thought to be high while the sensitivity is likely <90%. While testing can certainly miss COVID-19 as a result of the relatively poor sensitivity of the PCR viral swab, most of these patients will have a clinical picture that is consistent with COVID-19 and will be presumed to have the diagnosis even with a negative swab result.

North York General criteria for NP swab for COVID-19 screening as of March 20, 2020

*Note: indications for screening may vary by jurisdiction; this is simply an example for educational purposes

Outpatients: Fever OR mild symptoms of URI AND any of:

-

-

High risk of deterioration (elderly, immunocompromised, multiple comorbidities)

-

Those who work in vulnerable settings (prisons, homeless shelter, retirement home)

-

Those who work within at-risk settings (i.e. hospitals, long-term care, paramedics)

-

Travel is no longer a criterion for swabbing

Inpatients: URI symptoms AND being admitted to internal medicine service

Laboratory clues to COVID-19

Lymphocytopenia is present in >80% in patients and is probably the most useful lab test in distinguishing COVID-19 from other causes of respiratory infection.

Nonspecific lab abnormalities include elevated LDH, AST, ALT, elevated D-dimer, abnormal WBC.

Troponin and CRP may be a predictor of mortality and severe illness, and should be considered in patients who are going to be admitted.

While influenza co-infection has been reported with COVID-19, our expert recommends leaving the decision to test for influenza to the inpatient team, your local infection control specialists or public health authorities. There may be a role for testing for influenza for all ICU patients admitted with suspected COVID-19, as some patients may benefit from neuraminidase inhibitors.

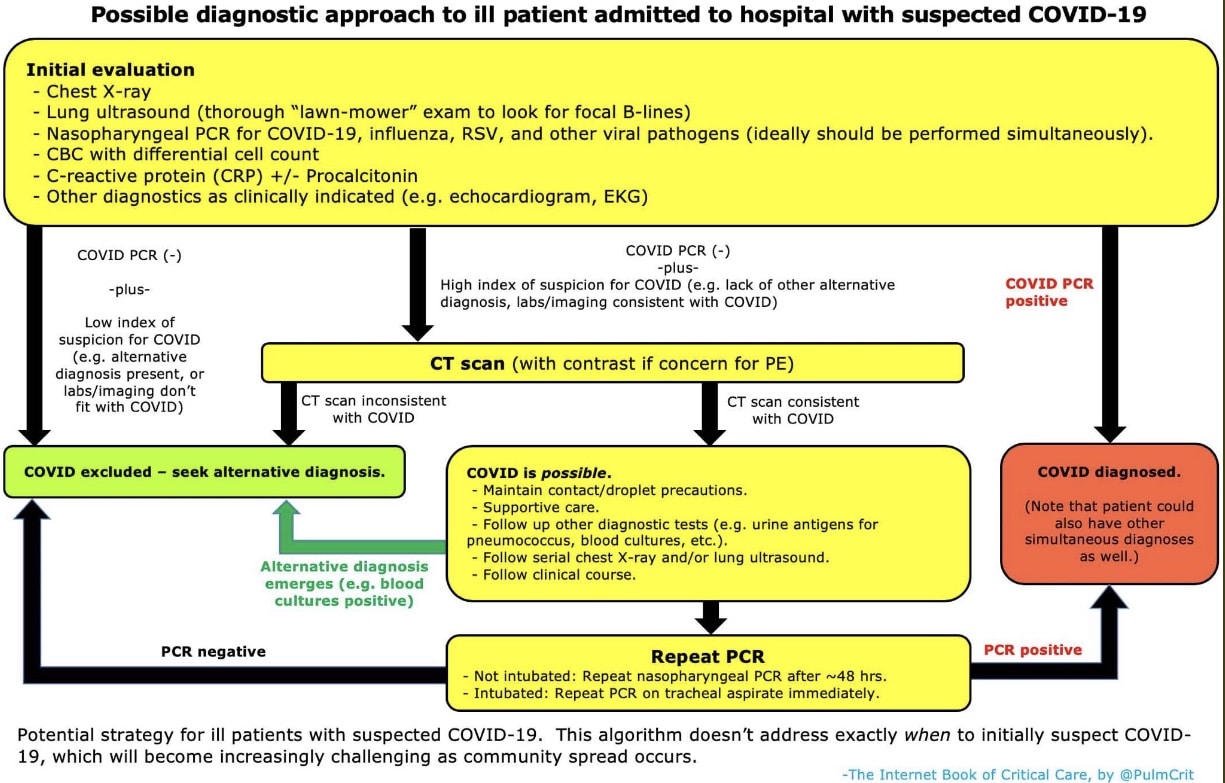

Imaging in COVID-19

CXR

The typical CXR findings are a bilateral interstitial pattern/ground glass opacities, with isolated focal infiltrate making the diagnosis less likely, however CXR may be normal early in the disease course, so a normal x-ray does not rule out the diagnosis.

CT

CT is more accurate than CXR and has been use as a screening tool, however our expert does not recommend screening with CT unless swabs are unavailable or lab reporting is delayed, in patients who are ill enough to be admitted to hospital.

Lung POCUS

POCUS findings correlate well with CT findings for COVID-19 and there have been reports that lung ultrasound may be helpful for patients with a high clinical suspicion of COVID-19 but negative PCR screening if they demonstrate typical lung ultrasound findings for COVID-19. For emergency providers with excellent POCUS skills and poor access to CT it is not unreasonable to use POCUS to aid in the diagnosis and rule out other acute respiratory illnesses, however POCUS should not be used a screening test for COVID-19 at present.

Clinical diagnosis of COVID-19 is cough and/or fever, lymphocytpenia and bilateral ground glass opacities on chest x-ray.

COVID spread prevention strategies

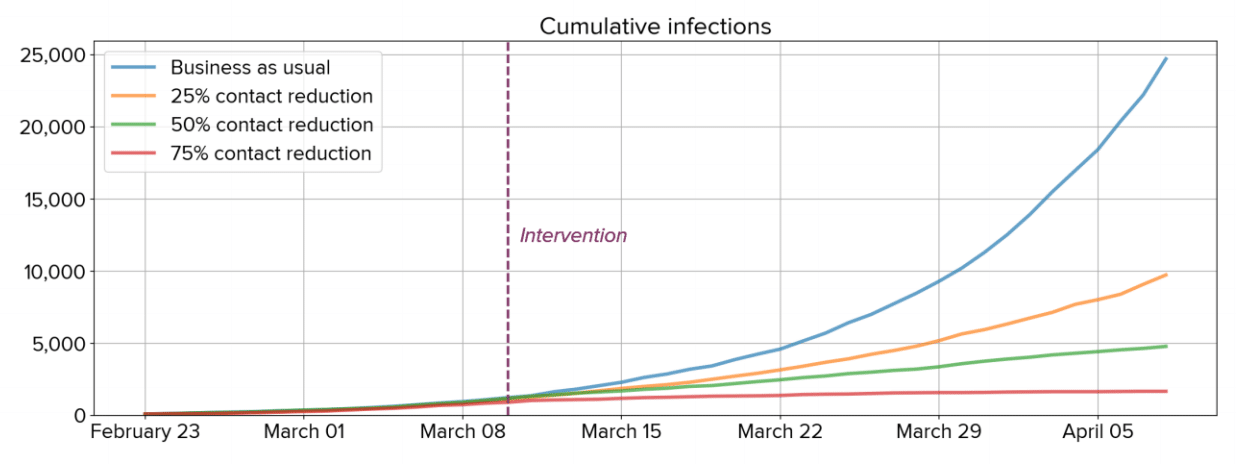

Social distancing does not stop all new cases overnight, but it greatly decreases case counts and fatalities over time

If everyone decreased their daily contacts by 25%, we would expect to see a 50% decrease in the cumulative number of cases over the next month (Klein et al., 2020-03-13).

Flattening the curve video with Mel Herbert

How long is the COVID outbreak likely to last?

It is our expert’s opinion that the earliest we will have an effective vaccine for COVID-19 will be June 2021. The degree of effectiveness of this vaccine will partially determine how long the COVID outbreak will last. Other factors include whether or not the virus mutates, implementation and compliance of social distancing and isolating measures, the number and size of second peak outbreaks, and strategies/timing of re-opening of country borders.

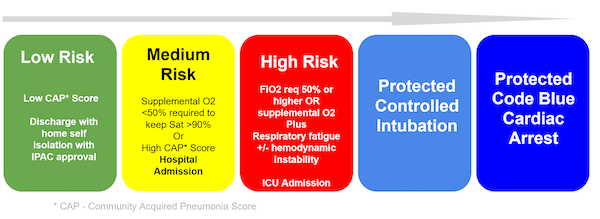

Disposition for COVID-19

The vast majority of patients can be safely discharged home.

Risk assessment to guide disposition (updated March 24th, 2020)

Use a *CAP Score of choice (anticipate at some point there will be a COVID 19 Severity Score)

Low Risk: These are well patients who are likely safe to be discharged home. When numbers are low this will be done with the approval of IP&C and Public Health (PH). If numbers get high, you will likely have a process put in place to discharge patients without IPC/PH approval just like you would do for influenza now. IPC/PH will likely want to know the patient’s name and contact information so they can track them. You should also have written instructions for patients about how to self-isolate and a telephone hotline they can call for advice to avoid a return visit.

Medium Risk: High CAP Score or supplemental 02< 50% needed to keep 02 sat >90. Admit to hospital or COVID-19 treatment site (possible, if numbers are high).

High Risk: High CAP Score or Fi02> 50 % needed to keep sat >90% OR signs of respiratory fatigue or hemodynamic instability. Early referral or transfer to a hospital with ICU capacity to perform controlled intubation is key. If this is not rapidly available, your team must have a process in place to manage this patient and perform airway management safely. Video or teleconsulting may be available in some areas.

Management of COVID-19

Respiratory risk assessment to guide management (updated March 24th, 2020)

Adapted from First10EM by Justin Morgenstern

General respiratory support

A rapid assessment from outside the room should place the patient in one of three categories:

- Mild hypoxia/ respiratory distress: nasal prongs, target oxygen saturation ≥ 88%; consider a surgical mask over the nasal prongs to limit viral spread.

- Moderate hypoxia/ respiratory distress: Patients that don’t look like they will need to be intubated in the first 4 hours of their hospital stay. Apply the HiOx non-rebreather oxygen mask and titrate to an oxygen saturation ≥ 88%. Any patients on HiOx or requiring oxygen flows of greater than 6 L/min should be placed on airborne precautions.

- Consider early phone call between the ED physician and the anesthesiologist and intensivist on call to facilitate safest timing of intubation.

- If there is any doubt about how sick the patient is, err on the side of intubating early.

- If the HiOx mask is not available, a standard non-rebreather can be used as an alternative. However, a standard non-rebreather is an open system without any filters. If using a standard non-rebreather, place a surgical mask over the nonrebreather to cover the exhalation ports.

- Severe hypoxia/ respiratory distress: If the patient is in severe distress and it appears that they will need intubation within the next few hours, do not delay intubation. If there is a strong indication to move the patient before intubation (more controlled situation, more experienced staff, better equipment), that may be reasonable, but consider the risks of transferring a patient with an uncontrolled airway.

Currently there is no specific targeted evidence-based treatment or vaccine for Covid-19. The approach to this disease is to control the source of infection; use of personal protection and precaution to reduce the risk of transmission; and early isolation and supportive treatments for affected patients.

Drugs for COVID-19 that have shown in vitro benefit

- Chloroquine

- Hydroxychloroquine

- Lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra)

- Remdesivir

- Tocilizumab

COVID-19 drug studies

Lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra)

NEJM Lopinavir/ritonavir RCT of 199 patients showed no significant difference in time to clinical improvement, with a trend to mortality benefit as a secondary endpoint but the trial was stopped too early to determine a statistically significant mortality benefit. At present there is no convincing evidence for benefit or harm from Lopinavir/ritonavir in COVID-19 patients.

Hydroxychloroquine plus Azithromycin

A prospective, observational study of 36 hospitalized patients with confirmed COVID-19 showed that after 6 days of treatment, 70% of patients who received hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin were virologically cured compared to 12.5% in control group. There were no patient oriented outcomes.

PDF of hydroxychlorouqine and azithromycin for COVID-19 study

Note that azithromycin and chloroquine are QTc prolonging.

Hydroxychloroquine oral dosing: 400mg BID x1d, then 200mg po BID x4d

Chloroquine

A non-peer reviewed study from China compared 100 patients given chloroquine to controls and found greater inhibition of pneumonia, improved lung imaging findings, and shortening of disease course.

First10EM on poor evidence for chloroquine

Update 2021: PRINCIPLE is a multi-center, open-label randomized trial in the UK including high-risk COVID-19 outpatients (>65 years old, or above 50 years old with co-morbidities). Across 2530 randomized participants, inhaled budesonide improved time to recovery, and showed a signal to reduce hospital admissions or death (though results did not reach statistical threshold). Abstract

Update 2021: Adaptive trial (phase 3) randomized outpatients with COVID-19 (and severe disease risk factors) to receive various doses of intravenous REGEN-COV (combination of monoclonal antibodies, casirivimab and imdevimab) or placebo. REGEN-COV reduced COVID-19-related hospitalization or death, reduced viral load faster, and had a 4 day shorter time to symptom resolution (10 days vs. 14 days in placebo). Abstract

Update 2021: TOGETHER randomized clinical trial in Brazil of 1,497 adult patients with early COVID-19 (less than 7 days from symptom onset) treated with fluvoxamine (100 mg twice daily for 10 days) versus placebo. Treatment with fluvoxamine among high-risk outpatients with early-diagnosed COVID-19 reduced need for hospitalization or need for >6 hour emergency department observation. Differences in adherence between the treatment and placebo groups, a risk of bias associated with the per-protocol analysis, and an endpoint with unclear clinical relevance. Abstract

ACEi/ARBs and COVID-19

While there is theoretical reason to discontinue ACEi or ARBs in patients with COVID-19 because the virus has ACEi binding receptors, patients taking ACEi or ARBs who contract COVID-19 should continue treatment as per European, Canadian, and the United States cardiovascular societies.

Ibuprofen and COVID-19

There is no evidence that ibuprofen or other NSAIDS worsens the clinical course of COVID-19. The WHO does not recommend against the use of ibuprofen to treat COVID-19 symptoms.

COVID-19 in Older Patients

- Older patients, particularly those with multiple comorbid illnesses, have the highest mortality rate with COVID-19.

- CDC guidelines recommend that symptomatic (fever or cough) older adults and those with chronic medical conditions or who are immunosuppressed should have a low threshold for testing for COVID-19.

- During a shortage of testing kits and their reagents, criteria should be followed to ensure those who are at highest risk receive testing.

- Place older patients with non-respiratory symptoms in a separate area of the ED, away from those with suspected respiratory infections.

- Be sure to communicate slowly and clearly for those with sensory or cognitive limitations. Patients will no longer be able to read lips and clinicians and caregivers wearing masks may be disorienting for those with dementia and other cognitive impairment.

- Work with their Area Agency on Aging (AAA) and/or Department of Public Health (DPH) to provide community resources for home delivered groceries and medications. Social worker assistance for these cases will be very helpful.

Summary of COVID Surviving Sepsis Guidelines March 20th, 2020

Quote of the month: “And the people stayed home. And read books, and listened, and rested and exercised, and made art and played games, and learned new ways of being, and were still. And listened more deeply. Some meditated, some prayed, some danced. Some met their shadows. And the people began to think differently.

And the people healed. And, in the absence of people living in ignorant, dangerous, mindless, and heartless ways, the earth began to heal.

And when the danger passed, and the people joined together again, they grieved their losses, and made new choices, and dreamed new images and created new ways to live and heal the earth fully, as they had been healed.”

– Kitty O’Meara

Recommended COVID Resources

- Josh Farkas’ COVID-19 chapter in the Internet Book of Critical Care

- REBEL EM COVID page

- COVID one-pager from Seattle intensivist

- Surviving Sepsis COVID Guidelines March 19th, 2020.

- How to self-isolate – Ontario Guide

- How to self-monitor – Ontario Guide

- Video discharge instructions for patients

- Strategies for Optimizing the Supply of N95 Respirators during the COVID-19 Response

- ACEP wellness assistance program – 3 free counseling sessions for ACEP members

- Evidence based summary of pediatric COVID-19 literature

References

- Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of 21 Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 29.

- Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok K, To KK, Chu H, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020 Jan 24. [Epub ahead of print]

- Hoehl S, Berger A, Kortenbusch M, Cinatl J, Bojkova D, Rabenau H, Behrens P, Böddinghaus B, Götsch U, Naujoks F, Neumann P. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Returning Travelers from Wuhan, China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020 Feb 18.

- The Epidemiological Characteristics of an Outbreak of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) in China]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(2):145–151. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003.

- Shah, N. Higher co-infection rates in COVID19. https://medium.com/@nigam/higher-co-infection-rates-in-covid19-b24965088333

- Wang YXJ, Liu WH, Yang M, Chen W. The role of CT for Covid-19 patient’s management remains poorly defined. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(4):145.

- Huang Y, Wang S, Liu Y, et al. A preliminary study on the ultrasonic manifestations of peripulmonary lesions of non-critical novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19). SSRN 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3544750.

- Peng Q, Wang X, Zhang L. Findings of lung ultrasonography of novel corona virus pneumonia during the 2019–2020 epidemic. Intensive Care Med 2020. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-05996-6.

- Nextstrain.org

- Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, et al. Cardiovascular Considerations for Patients, Health Care Workers, and Health Systems During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. Journal pre-proof available: http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/early/2020/03/18/j.jacc.2020.03.031. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- Gautret et al. (2020) Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents – In Press 17 March 2020.

- Gautret et al. (2020) Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents – In Press 17 March 2020 – DOI : 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

- Statement from the American Heart Association, the Heart Failure Society of America and the American College of Cardiology [press release]. 2020 Mar 17. (https://www.hfsa.org/patients-taking-ace-i-and-arbs-who-contract-covid-19-should-continue-treatment-unless-otherwise-advised-by-their-physician/)

- Fang L et al. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 2020 Mar 11; [e-pub]. (https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8)

- https://hypertension.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2020-30-15-Hypertension-Canada-Statement-on-COVID-19-ACEi-ARB.pdf?fbclid=IwAR0NPRt93gVo_QS-RUyr4B2hHDXtjQ6JP_K1WwhVoY3sj6N8bLMWmNp1xdc. Accessed March 19, 2020.

- European Society of Cardiology. Position Statement of the ESC Council on Hypertension on ACE-Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers. https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-on-Hypertension-(CHT)/News/position-statement-of-the-esc-council-on-hypertension-on-ace-inhibitors-and-ang?fbclid=IwAR1qYxXs90rs5XFJAolF3Z_WF7QQkSobN_gqLS8zyYblpr6xagH5xFSK-Yg. Accessed March 19, 2020.

Drs. Helman and Morris have no conflicts of interest to declare

What seems to be the consensus around head protection with the aerosol generating procedures…it seems to me that peoples hair will be as contaminated as much as the gloves, visors etc. The WHO PPE recommandations seem not to exige that the head be covered, I would be interested to hear what people are doing elsewhere with respect to this query.

Thanks and hang tough to all.

Hugh Scott

Quebec City

Aerosol generating procedures should certainly always include head covering. More here: https://emergencymedicinecases.com/biohazard-preparedness-protected-code-blue/ and next podcast will interview Laurie Mazurik expert in PPE.

absolutely wonderful .very practical and summ up

Favipiravir a broad spectrum anti RNA viralcide has been quoted as useful by Zhang Xinmin an official in China claiming a median 4 day negative after positive for COVID -19 but needs to be given early at onset of dry cough and fever days before some get pneumonia .

Favipiravir a broad spectrum inhibitor of Viral RNA polymerase Furuta Y Komeno T Nakamura in Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci Aug 2 449-463

Thanks Dr Helman, I agree with the take ownership attitude but we are in a top down decisional context presently…infection control does not seem to appreciate down up commentary. Are the Toronto hospitals donning head protection as per the recommendations of Dr Mazurik for AGMP’s? People are talking about using «kitchen catcher» plastic bags as per a youtube video if IPC sticks with they current recommendations.

Thank you Dr Helman,

Very informative review, looking forward to the next one.

Hello all,

is there any body in the world looking at movidyn- form of silver coloid as possible treatment for corona virus its history is anti microbial agent from Cold War days as antidote for germ warfare -I think some may looked at it regarding sears few years ago.Just thinking out loud and putting it out there for opinions -it was discovered in the 1950s by the Ceczs Scientists before 1957 revolution against the soviets -then taken back to Soviet Union after 1957 as antidote for biological warfare app works reg viruses and bacteria.

Cheers,

John P. Hayden ED prince county Hospital PEI Canada.

Thanks for the post. Love the poem at the end. It seems the credit would be due to a “Kitty O’Meara”. Based on “OprahMag”…

https://www.oprahmag.com/entertainment/a31747557/and-the-people-stayed-home-poem-kitty-omeara-interview/