Topics in this EM Quick Hits podcast

Salim Rezaie on clinical probability adjusted D-dimer for pulmonary embolism (1:21)

Bourke Tillmann on ARDS for the ED Part 2 – the vented ARDS patient in the ED (7:26)

Brit Long & Michael Gottlieb on pharyngitis mimics (15:29)

Justin Hensley on the many faces of barotrauma (24:04)

Hans Rosenberg & Peter Johns on assessment of continuous vertigo – HINTS vs MRI (32:41)

Justin Morgenstern & Jeannette Wolfe on gender-based differences in CPR (37:36)

Podcast production, editing and sound design by Anton Helman. Voice editing by Raymond Cho and Sheza Qayyum

Podcast content by Salim Rezaie, Bourke Tillmann, Brit Long, Michael Gottlieb, Justin Hensley, Hans Rosenberg, Peter Johns, Justin Morgenstern, Jeannette Wolfe and Anton Helman

Written summary & blog post by Graham Mazereeuw, edited by Anton Helman

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A. Rezaie, S. Tillman, B. M. Long, B. Gottlieb, M. Hensley, J. Rosenberg, H. Johns, P. Morgenstern, J. Wolfe, J. EM Quick Hits 23 – Clinical Probability Adjusted D-dimer, ARDS Part 2, Pharyngitis Mimics, Barotrauma, Vertigo, CPR Gender-Based Differences. Emergency Medicine Cases. October, 2020. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-october-2020/. Accessed [date].

Clinical Probability Adjusted D-Dimer: The PEGeD Study

- PEGeD Study – prospective study of 2,017 patients presenting to the ED with symptoms of pulmonary embolism (NEJM, 2019)

- Approach:

- 7-item Wells clinical prediction rule used to delineate low (0-4), moderate (4.5-6) or high (>6.5) risk of pulmonary embolism

- Low risk group (n=1,752): discharged without CTPA if d-dimer below 1,000 ng/ml FEU

- Moderate risk group (n=218): discharged without CTPA if d-dimer below 500 ng/ml FEU

- High risk group (n=47): sent directly for CTPA

- Zero patients discharged without CTPA based on adjusted d-dimer cutoffs had a pulmonary embolism at 3 months

- 17.6% reduction in CTPA use with adjusted d-dimer cutoffs compared to a universal cutoff of 500 ng/ml FEU

Bottom line: consider using clinical probability adjusted d-dimer cut offs if your ED has a typically low risk population

- Kearon C, de Wit K, Parpia S, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism with d-dimer adjusted to clinical probability. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(22):2125-2134.

- Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(2):98-107.

- Anand Swaminathan, “PEGeD Study – Is It Safe to Adjust the D-Dimer Threshold for Clinical Probability?”, REBEL EM blog, December 16, 2019. Available at: https://rebelem.com/peged-study-is-it-safe-to-adjust-the-d-dimer-threshold-for-clinical-probability/.

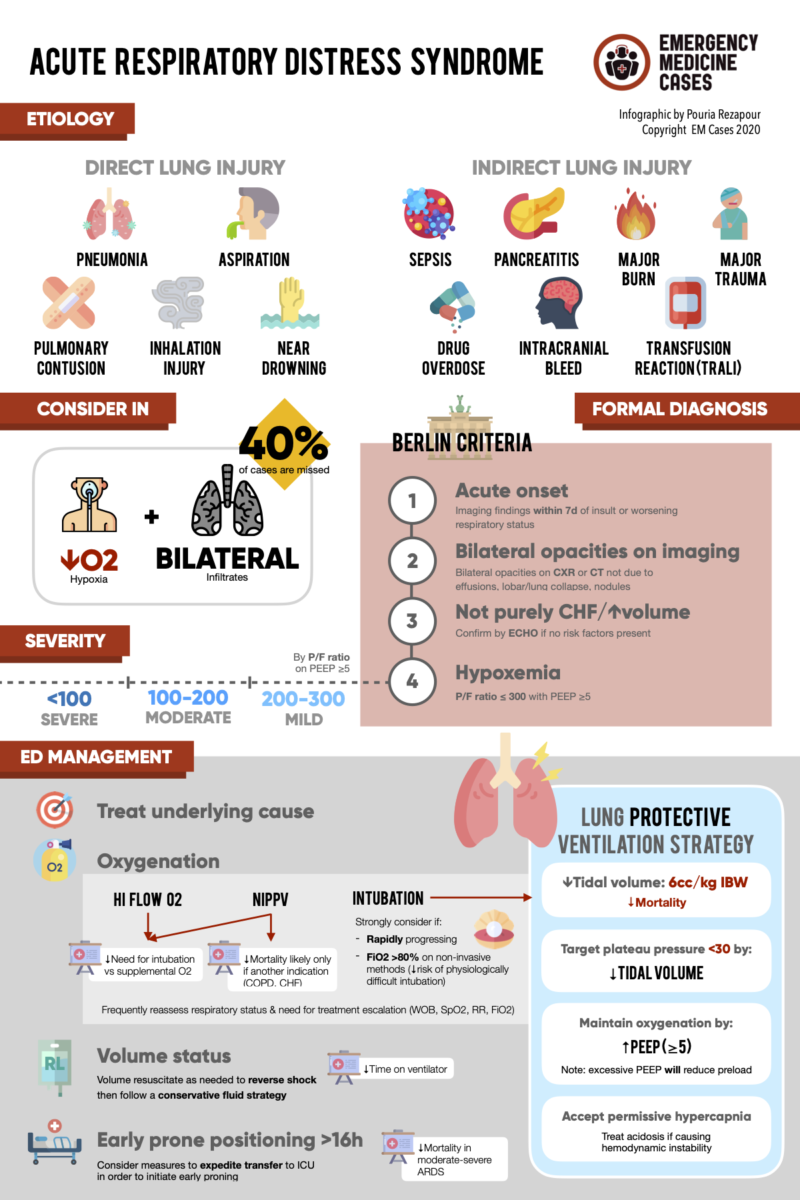

ED Management of ARDS Part 2: The Vented ARDS Patient in the ED

- Optimize oxygenation

- Titrate PEEP to minimize FiO2; balance increased oxygenation with decreased blood pressure (PEEP can reduce preload) as you up-titrate the PEEP

- Monitor intrathoracic pressure when titrating PEEP, stay at <30 cm H2O as indicated by plateau pressure on the vent

- Low tidal volumes

- Tidal volume of 6 cc/kg of ideal body weight confers greater survival than 12 cc/kg ideal body weight; keep ideal body weight tables at the bedside for convenient calculation

- Increase respiratory rate to compensate for hypercapnia associated with low tidal volume

- Minimize fluids

- Although fluid resuscitation may be necessary to stabilize the acutely ill patient, conservative fluid use can reduce the time spent on a ventilator

- Expedite prone positioning

- Prone positioning early and for at least 16 hours is associated with improved survival in ARDS

- Avoid routine use of paralysis

- Recent evidence shows that paralysis confers no mortality benefit in ARDS when compared with supportive care and lighter sedation

- Brower RG, Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, et al. Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(4):327-336.

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301-1308.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2564-2575.

- Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard J-C, et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2159-2168.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute PETAL Clinical Trials Network, Moss M, Huang DT, et al. Early neuromuscular blockade in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):1997-2008.

- ED Approach to ARDS Part 1 (at 33:56): https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-september-2020/

Pharyngitis mimics

- Pharyngitis is usually straightforward, but there are several dangerous mimics including epiglottitis, acute retroviral syndrome, peritonsillar abscess and retropharyngeal abscess to consider in patients presenting with sore throat and fever; prior EM Quick Hits episodes have covered Ludwig’s angina, Lemierre’s syndrome, and Kawasaki’s disease

- Epiglottitis occurs with inflammation of the supraglottic airway structures, most commonly due to infection

- In patients with fever, sore throat and a relatively normal appearing pharynx, think epiglottitis

- Stridor and tripoding are clues for impending obstruction which can occur suddenly; these are predicted difficult airways

- Involve ENT and anesthesia early; intubate in the OR, with a surgical airway prepared

- Nasopharyngoscopy is your imaging of choice if available, otherwise lateral neck XR (thumbprint sign) or CT if stable

- Give antibiotics and steroids ASAP

- Pearl: these patients often prefer to sit up/tripoding (vs. retropharyngeal abscess patients usually prefer to lie flat)

- Acute retroviral syndrome occurs in the first several months of HIV infection

- Patients present with pharyngitis and flu like symptoms making it difficult to distinguish from other types of pharyngitis, however one clinical clue is the presence of generalized lymphadenopathy

- Think of this condition in pharyngitis patients with generalized lymphadenopathy, symptoms lasting ≥ one week or other risk factors for HIV

- Peritonsillar abscess is a purulent fluid collection between the tonsillar capsule and posterior pharyngeal muscles

- The diagnosis is clinical with unilateral peritonsillar swelling and deviation of the tonsils and uvula

- Ultrasound may assist in the diagnosis

- Drain the abscess using incision and drainage or needle aspiration (as effective as I &D), and provide antibiotics

- Pearl: cut the plastic covering of the needle to 1cm short of the needle length to avoid inserting too deep and hitting the carotid artery

- Retropharyngeal abscess is a suppurative, deep space infection of the neck, or the potential space between the posterior pharyngeal wall and prevertebral fascia

- Patients may present with neck stiffness, torticollis, trismus, voice change, or inability to tolerate oral secretions

- Clues to diagnosis: change in neck mobility or pain with neck movement, preference of patient to lie supine

- Lateral neck XR and/or CT can assist in the diagnosis

- Pearl: these patients prefer to lie flat (vs. epiglottitis patients prefer to sit up/tripoding)

References:

- Gottlieb M, Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical Mimics: An Emergency Medicine-Focused Review of Streptococcal Pharyngitis Mimics. J Emerg Med. 2018;54(5):619-629.

- Quick Hits episode 3, Kawasaki disease: https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-march-2019/

- Quick Hits episode 5, Ludwig’s angina: https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-june-2019/

- Quick Hits episode 8, Lemierre syndrome: https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-september-2019/

Barotrauma

- Barotrauma exists because of Boyle’s law: P1V1 = P2V2

- The higher the environmental pressure, the more air is compressed into a smaller volume

- Failure to equalize pressures while diving can cause vacuum and expansion injuries

- While barotrauma can occur in the sinuses, external auditory canal, middle ear and inner ear, the most life threatening barotrauma occurs with ascent barotrauma that includes pulmonary barotrauma and arterial gas embolism

- Pulmonary barotrauma

- Occurs with ascent without exhaling

- Causes alveolar hemorrhages, pneumothorax – both simple and tension

- Arterial gas embolism

- 5% will die immediately, 5% will die in hospital

- Nearly instant symptom onset: vertigo, headaches, stroke symptoms, MI, any embolism symptom…

- Treatment is a dive chamber, but on the boat treat with high flow oxygen and fluids (to maximize cerebral perfusion pressure)

- Pulmonary barotrauma

References:

- Battisti AS, Haftel A, Murphy-Lavoie HM. Barotrauma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

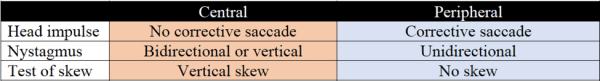

Assessment of constant vertigo: HINTS vs MRI

- HINTS has a greater sensitivity for stroke than MRI at less than 48 hours

- If any element favours a central cause, you must consider a central cause (most commonly a stroke)

- If HINTS positive, investigate with MRI after 48 hours (MRI can miss a cerebellar stroke < 48 hours), admit if needed

- If persistent vertigo and difficulty walking without observed nystagmus, the risk of a central lesion (usually an ischemic stroke) should not be considered to be low

Bottom line: MRI is not sensitive enough to rule out stroke until 48 hours after the insult.

Update 2023: A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the diagnostic accuracy of physical exam findings for central versus peripheral causes in acute vertigo found that a general neurological examination had a sensitivity of 46.8% (95% CI 32.3-61.9%), and specificity of 92.8% (95% CI 75.7-98.1%). HINTS had a sensitivity of 92.9% (95% CI 79.1-97.9%), and specificity of 83.4% (95% CI 69.6-91.7%). HINTS+ (HINTS with hearing component) had the highest sensitivity at 99% (95% CI 73.6%-100%), and specificity of 84.8% (95% CI 70.1-93.0%). Abstract

References:

- Johns P, Rosenberg H. Just the Facts: How to assess a patient with constant significant vertigo and nystagmus in the emergency department. CJEM. 2020;22(4):463-467.

- Quick Hits, episode 11: https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-december-2019/

- Video demonstrating the HINTS exam: https://emcrit.org/emcrit/posterior-stroke-video/

- Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh Y-H, Newman-Toker DE. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009;40(11):3504-3510.

- EM Cases approach to vertigo: https://emergencymedicinecases.com/wp-content/uploads/filebase/pdf/EMC%20045%20Jun2014%20EMU1%20Summary.pdf

- Machner B, Choi JH, Trillenberg P, Heide W, Helmchen C. Risk of acute brain lesions in dizzy patients presenting to the emergency room: who needs imaging and who does not? J Neurol. Published online May 27, 2020.

Gender-based differences in CPR

- Increasingly recognized that gender differences can affect cardiovascular risk

- Highest 30-day mortality from a STEMI is among females younger than 55 years old

- Diabetes and cigarette smoking are stronger risk factors for cardiovascular disease in females than in males

- Gender now also recognized to influence resuscitation outcomes

- If collapse at home, men and women have an equal chance of receiving bystander CPR

- If collapse in public, men (45%) are more likely to receive CPR than women (39%)

- Reasons bystanders might be reluctant to perform CPR on a woman

- Potential for inadvertent intimate touching or an erroneous sexual assault charge

- Women perceived as frailer than men and may be seriously injured by CPR

- Less suspicious of a cardiac cause when a woman collapses

Bottom line: Sex and gender confer important disparities in health outcomes and must continue to be addressed in research and clinical training

References:

- Blewer AL, McGovern SK, Schmicker RH, et al. Gender disparities among adult recipients of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the public. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(8):e004710.

- Perman SM, Shelton SK, Knoepke C, et al. Public perceptions on why women receive less bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation than men in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2019;139(8):1060-1068.

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare

Great podcast as per usual !

I also find it hard to remember gender Vs sex Vs attraction Vs expression

I think Maggie Smiths “Genderbread person “ does a neat job reminding us https://www.publichealthpost.org/databyte/genderbread-person/

Thanks for the review

Emergency Medicine Abstracts August 2018 reviewed a study where peritonsillar abscess was first given antibiotics and steroids and most patients avoided I&D

About the quick hit on adjust D-dimers threshold based on pre-test probability, it was mentionned that the PEGed approach was not validated in pregnant women.

However, an adapted YEARS algorithm was validated in pregnancy and reduced up to 32-65% of pulmonary angiography.

There is the references:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30893534/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7078738/

Thank you for sharing PEGeD Study – I tried it with my low risk patient and later did follow-up; and I believe it was the right decision. This is really a game changer.