Pediatric seizures are common. So common that about 5% of all children will have a seizure by the time they’re 16 years old. If any of you have been parents of a child who suddenly starts seizing, you’ll know intimately how terrifying it can be.

While most of the kids who present to the ED with a seizure will end up being diagnosed with a benign simple febrile seizure, some kids will suffer from complex febrile seizures, requiring some more thought, work-up and management, while others will have afebrile seizures which are a whole other kettle of fish. We need to know how to differentiate these entities, how to work-them up and how to manage them in the ED. At the other end of the spectrum of disease there is status epilepticus – a true emergency with a scary mortality rate – where you need to act fast and know your algorithms like the back of your hand. This topic was chosen based on a nation-wide needs assessment study conducted by TREKK (Translating Emergency Knowledge for Kids), a collaborator with EM Cases.

With the help of two of Canada’s Pediatric Emergency Medicine seizure experts hand picked by TREKK, Dr. Lawrence Richer and Dr. Angelo Mikrogianakis, we’ll give you the all the tools you need to approach the child who presents to the ED with seizure with the utmost confidence.

Written Summary and blog post Prepared by Michael Kilian, edited by Anton Helman, Nov 2015

Cite this podcast as: Richer, L, Mikrogianakis, A, Helman, A. Emergency Management of Pediatric Seizures. Emergency Medicine Cases. November, 2015. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/emergency-manage…diatric-seizures/. Accessed [date].

Step 1: Distinguish Pediatric Seizures vs. Pediatric Seizure mimics

Much of the distinction between true pediatric seizures and mimics will hinge on elements gathered from the history. Ask about the onset, duration, nature of the movements, tongue biting, eye findings and details of the recovery phase. A history of incontinence can be helpful in older children who are no longer in diapers. The presence or absence of an aura will only be helpful in children who are able to provide a clear account of their experience. Be sure to ask the parents what the eyes, neck and head were doing at the time of the seizure. The recovery phase is also important since a rapid return to normal activity speaks against a true seizure.

Elements that are highly suggestive of true seizure activity include:

- Lateralized tongue-biting (high specificity)

- Flickering eye-lids

- Dilated pupils with blank stare

- Lip smacking

- Increased heart rate and blood pressure during event

- Post-ictal phase

Distinguishing Breath-holding spells from Pediatric Seizure

Breath holding spells are most common in the 6-18month age range. One of the key differentiating factors is that there is usually a clear trigger for a breath holding spells such as emotional distress or pain, whereas seizures typically do not have such precipitants. This pattern of an initiating trigger, followed by emotional upset, crying, pallor, and occasionally LOC is highly suggestive of a breath holding spell. The breath holding and LOC can lead to brief seizure activity given the decrease cerebral blood-flow. However, the recovery from a breath-holding spell is rapid and complete without a post-ictal phase.

Distinguishing Pseudo-Seizures from True Seizure

These tend to be seen in the adolescent population since younger children cannot feign seizure activity for secondary gain. Features that distinguish these events from true seizures include side-to side head, arm or leg movements with eyes closed. If the eyes are open, the eye movements are normal as opposed to deviated. A bicycling movement of the legs is highly suggestive of pseudo-seizure.

Distinguishing Syncope from Seizure

Syncopal episodes may or may not have a clear precipitant but the LOC always precedes any perceived seizure activity. Observers may note some brief twitching episodes as opposed to true tonic-clonic movements. The recovery from a syncopal episode is rapid and complete.

Step 2: Distinguish Simple vs. Complex Febrile Seizure

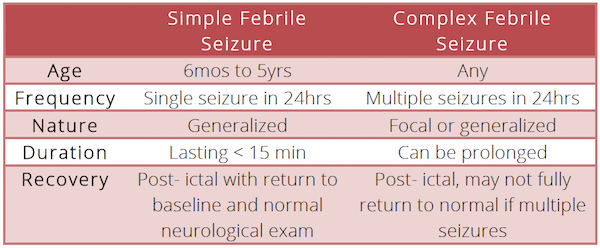

Once you have established that the child did in fact have true seizure activity in the context of a fever, the next step is to clearly define whether it fits the pattern of a simple or a complex febrile seizure. A diagnosis of complex febrile seizures is made if there is any deviation from the criteria of a simple febrile seizure. This distinction is important because complex seizures may indicate a more serious disease process and usually require a work-up.

Simple febrile seizures tend to occur early in the illness within 24hrs of onset of fever –

if the seizure occurs >24hrs after the onset of fever, the suspicion for a bacterial cause of the fever

and a pathologic cause for the seizure should be heightened.

Which Patients with Febrile Seizures Require a Work-up?

If the child meets the criteria for a simple febrile seizure, no dedicated seizure workup is required and you evaluate the patient as if they solely had a fever. It is clear in the literature that children who have suffered a simple febrile seizure are at no greater risk for serious bacterial infection than age-matched controls who have not seized. A child who fits the criteria for a simple febrile seizure should be worked up as if they presented with fever and no seizure. Studies have shown that measurement of serum electrolytes or glucose in particular has no role in the workup of simple febrile seizures. A workup beyond a basic febrile workup should be considered if the child appears unwell or meets any of the criteria of a complex febrile seizure.

Our experts recommend the workup of complex febrile seizures to be a step wise approach, keeping in mind that the younger the child the more aggressive the work-up should be. Children who return to baseline after a complex seizure and at no point displayed any focal neurologic symptoms usually do not require an extensive work-up. Even though studies have shown that febrile seizures do not increase the risk of serious bacterial infection compared to fever alone, meningitis should always be on the differential diagnosis in a child with complex febrile seizures. About 25 % of children with meningitis will present with a new onset febrile seizure, however they will almost always display persistent mental status abnormalities along with other signs of meningitis such as nuchal rigidity, focal siezures and petechia.

Update 2018: A retrospective study including over 28,000 patients (ages 0-5) with complex febrile seizures showed a very low incidence of CNS infections, suggesting lumbar punctures are low-yield in this population. Caution was warranted in those who are unvaccinated, pre-treated with anti-biotics or had suspicious symptoms/signs of CNS infection. Abstract

Update 2021: Retrospective cross-sectional analysis of 49 tertiary care pediatric hospitals across USA including 142,121 children presenting with a simple febrile seizure (SFS). From 2005-2019, found decline in rates of lumbar punctures (LP) from 11.6% to 0.6%, head CT’s from 10.6% to 1.6%, hospital admissions from 19.2% to 5.2%, and mean costs from $1,523 to $601. No significant change in delayed diagnosis of bacterial meningitis; supporting that children with SFS’s can be safely managed without LP or additional diagnostic testing. Abstract

Counseling Parents about Pediatriac Seizures

Safety – place the child in the recovery position and do not place anything in the child mouth

Risk of recurrence is approximately 33% overall with a higher risk in children

- temperature < 40.0°C at first convulsion

- family history of febrile seizures

If they have all 4 of the factors, their risk of recurrence is 70%. If they don’t meet any criteria, their risk falls to 20%.

Risk of Epilepsy is approximately 2% after a simple febrile seizure and 5 % after a complex febrile seizure (compared to 1% in the general population)

Parents will often blame themselves for not treating the seizure appropriately or quickly enough to prevent the seizure. It is important to educate them that the height of the fever or rapidity of onset does not predict risk of suffering a seizure and that prophylactic antipyretics do not decrease the rate of seizure recurrence.

Non-febrile Pediatric Seizures

The differential diagnosis of non-febrile pediatric seizures is extensive, encompassing metabolic derangements to mass lesions to non-accidental trauma.

Hyponatremia secondary to over-dilution of infant formula

One particular diagnosis that is one of the more common causes of non-febrile seizure in children under 6months of age and that is relatively easy to pick up thus avoiding an extensive invasive work-up is hyponatremia secondary to formula over-dilution. In a paper from the Annals of EM, hyponatremia was the cause of seizures in 70% of 47 infants younger than 6 months who lacked other findings suggesting a cause. They found that a temperature of 36.5°C or less as the best predictor of hyponatremic seizures.

If a pediatric patient with hyponatremia as a cause for their seizures seizes in the ED, they should be treated with 3cc/kg of hypertonic (3%) normal saline.

Physical Examination Pearls for Non-febrile Pediatric Seizures

Looking for the following signs can help in the workup of a non-febrile seizure:

Skin Look for lesions such as cafe au lait spots (neurofibromatosis), adenoma sebaceum or ash leaf spots (tuberous sclerosis), and port wine stains (Sturge-Weber syndrome). Unexplained bruising should raise the suspicion of a bleeding disorder or child abuse.

Head Examine for bulging fontanelle, microcephaly, dysmorphic features, signs of trauma, presence of a VP shunt.

Eyes Examine for papilledema and retinal hemorrhages

Neck Examine for signs of meningeal irritation.

Hepatosplenomegaly May indicate a metabolic or glycogen storage disease.

In patients who have no identifiable risk factors, an accurate and thorough history and physical examination

have been shown to yield more diagnostic information than a laboratory evaluation.

Work-up of Non-febrile Pediatric Seizures

Lab tests may not be necessary in a child who is alert and has returned to a baseline level of function and should be based on clinical suspicion.

Consider ordering laboratory studies on pediatric patients who:

- Have prolonged seizures,

- < 6 months of age (specifically for hyponatremia)

- History of diabetes, metabolic disorder, dehydration, or excess free water intake

- Altered LOC

Update 2015: Study finds that age < 2, first time seizure and seizure in the ED are characteristics which show a trend towards increased yield of blood work and CT head. Abstract

What is the role of a CT head in the work up of non-febrile pediatric seizures?

For non-febrile seizures, emergent neuroimaging is not necessary in children who have suffered their first non-febrile seizure and have returned to their baseline.

High risk factors on history of physical exam that should prompt consideration of neuroimaging include:

- Focal seizure or persistent seizure activity

- Focal neurologic deficit

- VP shunt

- Neurocutaneous disorder

- Signs of elevated ICP and history of trauma or travel to an area endemic for cysticercosis.

- Patients who have immunocompromising diseases (malignancy or HIV),

- Hypercoagulable states (sickle cell disease), or bleeding disorders

Disposition of Patients with Non-febrile Pediatric Seizures

Disposition of non-febrile seizures depends on age, serial physical examinations, initial work-up and follow-up capabilities

Under 6months of age – generally require a full workup and are usually admitted for observation.

6 months and 2 years of age – disposition will depend on blood work, reassessment and the ability to have close follow-up.

Over 2 years of age – those who have returned to baseline, have a normal neurological exam with normal workup are often safe to be discharged to close outpatient follow-up. Otherwise, admit.

Parents should be informed that approximately 50% of children who have a non-febrile seizure will have a recurrence.

Status Epilepticus in Emergency Management of Pediatric Seizures

Status Epilepticus (SE) was historically defined as any seizure activity lasting longer than 30mins, but this has changed in recent years. Given that we strive to terminate seizure activity long before 30min, SE is now more conservatively defined as a:

- Seizure lasting > 5 minutes, OR

- Consecutive seizures without a return to baseline in between

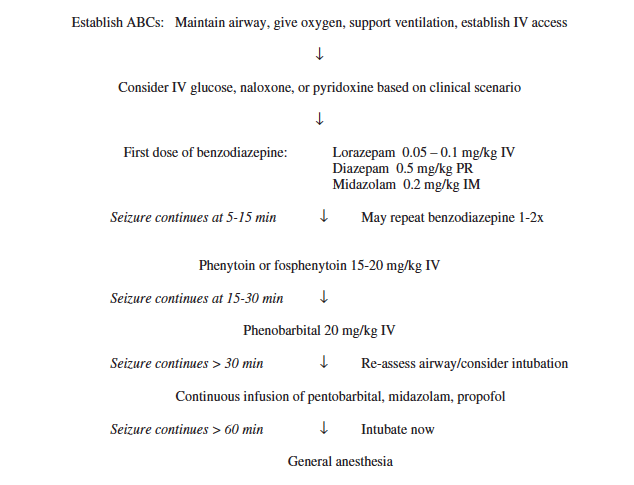

When you are faced with a seizing child, the priorities are the same as with any resuscitation: ABCs. Start by evaluating the airway and provide supplemental oxygen, then establish cardiac monitoring. The next steps will focus on terminating the seizure and the goal is to terminate all seizure activity within 60 seconds.

Administration of EARLY benzodiazepines is a priority!

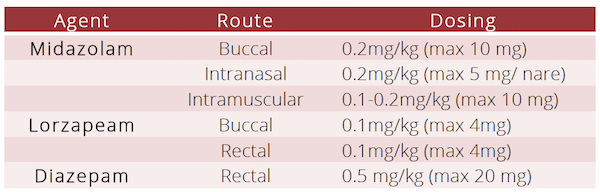

In an actively seizing child, IV and IO access may be difficult and time-consuming. For your first dose of benzodiazepines, consider either intranasal, buccal, intramuscular or rectal dosing of the following medications:

The choice of benzodiazepine and the choice of route is not the major determinant of efficacy.

Rather, the most important determinant of benzodiazepine efficacy in stopping seizures is

There have been many studies evaluating the different benzodiazepines and routes of administration. For example, in a pre-hospital setting, intramuscular midazolam was shown to be as effective at terminating seizures as intravenous lorazepam. In another randomized trial, buccal midazolam was superior to rectal diazepam at stopping seizure activity.

Update 2017: This systematic review of 11 studies found non-IV benzodiazepines (NIVB) were able to be given more quickly than IV benzodiazepines and stopped seizure activity >3 minutes sooner. NIVB were given by rectal, buccal, intranasal, or IM route. Abstract

Clinical Pearl: Once you have started giving your antiepileptic medications start drawing up the next dose of medication so that it is ready to administer if seizure activity continues to persist.

Pediatric Status Epilepticus Algorithm

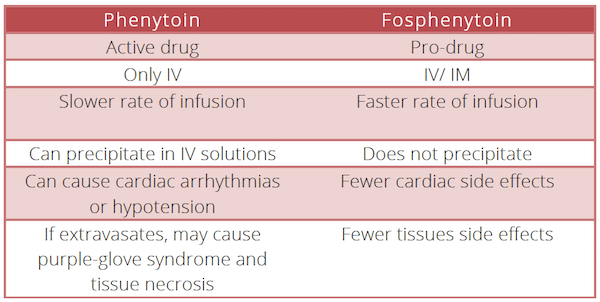

Second Line Agents in Status Epilepticus – Phenytoin vs. Fosphenytoin

Phenytoin and fosphenytoin are the same active medication. The difference between the two preparations lies in the side effect profile and the manner in which it can be administered. For these reasons fosphenytoin is the preferred second line agent for treatment of SE.

Phenytoin and fosphenytoin are less effective for the treatment of seizures due to toxins or drugs and may intensify seizures caused by cocaine, other local anesthetics, theophylline, or lindane. In such cases, an alternative second-line drug such as phenobarbital or valproate should be used.

Update 2019: Two multicentre, randomized controlled trials (EcLiPSE and ConSEPT) involving emergency treatment of pediatric convulsive status epilepticus compared second line agents levetiracetam to phenytoin, and showed levetiracetam was not superior to phenytoin. Abstract-EcLIPSE Abstract-ConSEPT

Update 2019: A single center well done RCT out of South Africa showed that phenobarbital stops twice as many seizures and achieves a non-convulsive state more than twice as fast as phenytoin in children with status epilepticus, suggesting that after benzodiazepines, phenobarbital is the most appropriate second line option in status epilepticus. EM Quick Hits 22 Phenobarbital in Status Epilepticus

Refractory Status Epilepticus

If, despite all the medications and efforts described above, your patients is still seizing, initiate continuous IV infusions of:

- Midazolam (120mcg/kg/hr and titrate upwards)

- Pentobarbital

- Propofol (contraindicated with ketogenic diet)

- Ketamine -a recent systematic review indicates 63.5% cessation rates in seizures in pediatric refractory status epilepticus, however our experts do not recommend it as a first line agent in this setting

Update 2022: A retrospective single center cohort study of pediatric patients (mean age 0.7 years) admitted to the ICU for refractory status epilepticus and treated with ketamine infusion found that ketamine infusion was followed by seizure termination in 46% of patients and seizure reduction in 28% of patients. 4% of patients had an adverse event requiring intervention including hypertension and delirium. Abstract

For more EM Cases content on Pediatric Emergencies check out our free interactive eBook,

EM Cases Digest Vol. 2 Pediatric Emergencies here.

For more Pediatric EM learning visit one of EM Cases collaborators trekk.ca – Translating Emergency Knowledge for Kids (TREKK) is a growing network of researchers, clinicians, health consumers and national organizations who want to accelerate the speed at which the latest knowledge in children’s emergency care is put into practice in general EDs – rural, remote or urban.

Key References

Patel N, Ram D, Swiderska N, Mewasingh LD, Newton RW, Offringa M. Febrile seizures. BMJ. 2015;351:h4240.

Berg AT, Shinnar S, Darefsky AS, et al. Predictors of recurrent febrile seizures. A prospective cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(4):371-8.

Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Predictors of epilepsy in children who have experienced febrile seizures. N Engl J Med. 1976;295(19):1029-33.

Neurodiagnostic evaluation of the child with a simple febrile seizure. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):389-94. Full PDF

Farrar HC, Chande VT, Fitzpatrick DF, Shema SJ. Hyponatremia as the cause of seizures in infants: a retrospective analysis of incidence, severity, and clinical predictors. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26(1):42-8. Full PDF

Warden CR, Brownstein DR, Del beccaro MA. Predictors of abnormal findings of computed tomography of the head in pediatric patients presenting with seizures. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29(4):518-23.

Hirtz D, Berg A, Bettis D, et al. Practice parameter: treatment of the child with a first unprovoked seizure: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2003;60(2):166-75. Full PDF

Alford EL, Wheless JW, Phelps SJ. Treatment of Generalized Convulsive Status Epilepticus in Pediatric Patients. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2015;20(4):260-89.

Welch RD, Nicholas K, Durkalski-mauldin VL, et al. Intramuscular midazolam versus intravenous lorazepam for the prehospital treatment of status epilepticus in the pediatric population. Epilepsia. 2015;56(2):254-62.

Mcintyre J, Robertson S, Norris E, et al. Safety and efficacy of buccal midazolam versus rectal diazepam for emergency treatment of seizures in children: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):205-10.

Chin RF, Neville BG, Peckham C, Wade A, Bedford H, Scott RC. Treatment of community-onset, childhood convulsive status epilepticus: a prospective, population-based study. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(8):696-703.

Shearer P, Park D. Seizures and Status Epilepticus: Diagnosis and Management in the Emergency Department. Emergency Medicine Practice. 2006; 8 (8). Full PDF

Zeiler FA. Early Use of the NMDA Receptor Antagonist Ketamine in Refractory and Superrefractory Status Epilepticus. Crit Care Res Pract. 2015;2015:831260.

Other FOAMed Resources on Pediatric Seizure

Pediatric seizure mimics on Pediatric EM Morsels

Management of adult status epilepticus on First10EM

Dr. Helman, Dr. Mikrogianakis & Dr. Richer have no conflicts of interest to declare

For more EM Cases content on Pediatric Emergencies check out our free interactive eBook,

EM Cases Digest Vol. 2 Pediatric Emergencies here.

[…] Medicine Cases has another great episode, this time about the emergency management of Paediatric Seizures. […]

Loved this episode, thank you so much for all the work that went into it!

Just one comment about psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (pseudoseizures). You mention that children often do not have the insight to feign seizure activity for secondary gain. My understanding is that psychogenic nonepileptic seizures are considered a subtype of conversion disorder, meaning that the patients actions are involuntary, and they do not have any clear insight into what they’re doing at the time. If you feel that the seizure activity is faked or feigned for secondary gain, this should lead more towards a diagnosis of malingering, which would be separate from PNES.

Perhaps it seems like semantics but I do think the distinction is important, especially for communication with parents and adolescents.

Thanks again!

Thanks for the clarification. I agree that there should be a distinction made between malingering and conversion disorder as they require different management strategies.