This is EM Cases Episode 99 Highlights from EMU 2017.

North York General Hospital’s 30th Annual Emergency Medicine Update (EMU) Conference 2017 featured some of the best talks I’ve ever heard from the likes of Sara Gray, Amal Mattu, David Carr and many more. I had a hard time choosing which talks to feature on this EM Cases podcast. I settled on a potpourri of clinical topics and practice tips: Leeor Sommer on Lyme disease, Chris Hicks on signover, Matt Poyner on patient complaints and Walter Himmel on acute vestibular syndrome…

Podcast production, sound design & editing by Anton Helman

Written Summary and blog post by Alexander Hart & Shaun Mehta, edited by Anton Helman August, 2017

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A, Sommer, L, Hicks, C, Poyner, M, Himmel, W. Highlights from EMU 2017. Emergency Medicine Cases. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/episode-99-highlights-emu-2017/. Accessed [date].

Lyme Disease from EMU 2017 with Leeor Sommer

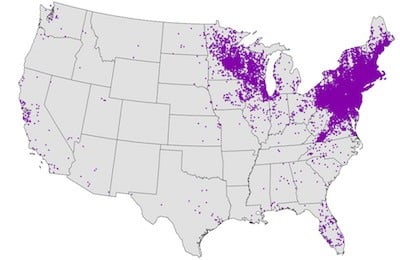

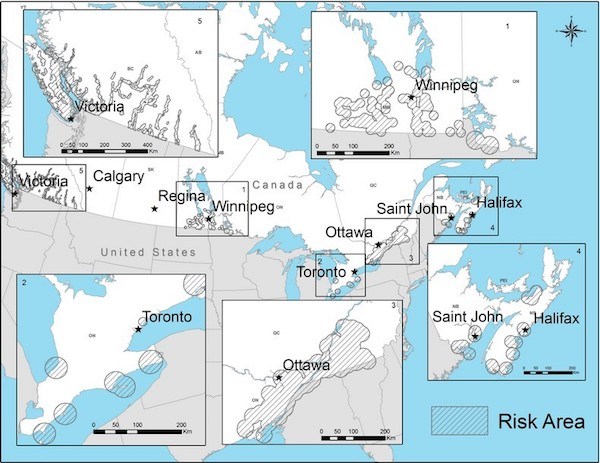

Lyme is spreading around North America and Europe and should now be considered endemic in many areas. The incidence is rising and might be much higher than is reported. Early diagnosis is key to preventing disseminated Lyme disease and treatment of acute Lyme disease is very effective.

Distribution of Lyme Disease U.S.

The Lyme Bug

Black legged Ixodes tick (care of Wikipidedia)

Borelia burgdoferi is spread via the black legged Ixodes tick.

Ixodes in its nymph form can also spread disease and at 1mm in size, can go undetected much more easily.

The Lyme Disease Presentation

Lyme disease has several presentations which can grossly be divided between acute Lyme disease and disseminated Lyme disease.

Acute Lyme Disease Presentation

About 3/4 of patients with acute lyme disease present with rash, fever, flu-like illness in the spring or summer months. Think of acute Lyme disease when a patient presents with a flu-like illness in these seasons.

The Rash of acute Lyme disease is most often the classic Erythema Migrans bull’s eye type, but can also be an erythematous patch with a central scab or simply one or more erythematous patches with blurred margins.

Erythema Migrans “Bull’s eye” rash of acute lyme disease

Erythmatous patch with central scab consistent with acute lyme disease

Disseminated Lyme Disease Presentation

A much more serious and refractory illness

Think of disseminated Lyme in the setting of:

- Bilateral 7th nerve palsy (this is almost pathognomonic)

- Aseptic meningitis in summer

- Heart block, including really long (>300ms) 1st degree HB (Lyme carditis)

- Acute mono-arthritis with large effusions of large joints.

Clinical Pearl: If a patient suspected of Lyme disease has a 1st degree heart block on ECG, consider admission as many of these patient will go on to develop 3rd degree heart block.

Lyme Disease Diagnosis

Remember that testing for Borelia early in the acute disease state will be negative. Borelia is a slow growing bacterium and does not trigger the IgM/IgG response the assay requires until much later. To prevent disseminated Lyme, treat on spec and assure follow-up testing in 2 weeks.

CDC suggested testing algorithm for suspected Lyme Disease

In the case of disseminated Lyme, tests should be positive.

There is no test of cure. Once positive, patients are often positive for life. This is particularly challenging when dealing with post-treatment Lyme syndrome which can leave patients feeling sick for months to years after infection clearance.

Treatment of Lyme Disease

Acute Lyme

Doxycycline is first line (10 days up to 3 weeks).

Amoxicillin or cefuroxime in patients 8 years or younger.

If allergic, macrolides (more frequent treatment failures).

Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid if the differential between cellulitis and erythema migrans is unclear (treats both).

Disseminated Lyme

IV ceftriaxone or Penicillin G.

Doxycycline is first line in Lyme arthritis but may require 2-3rd line agents.

Asymptomatic Tick Bite

Grab the tick by the head with surgical forceps. Take out as much as possible.

If the tick is present for <24hrs, the risk of developing Lyme is extremely low.

If the tick has been present >24hrs or unknown:

Prophylaxis options include

- Watchful waiting

- Treat with single dose 200mg Doxycycline

- Treat with full course 14 days Doxycycline or 10 days Amoxicillin in <8y/o

NNT to prevent erythema migrans: 50

NNT to prevent disseminated Lyme: 160

NNT if tick is engorged with blood: 11

Update 2023 Management of Tick Bites and Investigation of Early Localized Lyme Ontario Guide

References for Lyme Disease

Government of Canada website. Lyme Disease for professionals. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/lyme-disease/health-professionals-lyme-disease.html

Steere AC, Sikand VK. The presenting manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:2472.

Gary P. Wormser et al. The Clinical Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention of Lyme Disease, Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, and Babesiosis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. IDSA Guidelines 2006.

Krupp LB, Hyman LG, Grimson R, Coyle PK, Melville P, Ahnn S, Dattwyler R, Chandler B. Study and treatment of post Lyme disease (STOP-LD): a randomized double masked clinical trial. Neurology 2003 Jun 24;60(12):1923-30.

Cameron DJ et al. Evidence assessments and guideline recommendations in Lyme disease: the clinical management of known tick bites, erythema migrans rashes and persistent disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Therapy. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014 12(9): 1103-35.

Warshafsky S, et al. Efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of lyme disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J antimicrob chemother, 2010 jun;65(6):1137-44.

Other FOAMed Resources on Lyme Disease

CORE EM podcast on Lyme disease

EMDocs Lyme disease ED presentations/Management Pearls and Pitfalls

Pediatric Lyme on Pediatric EM Morsels

An Approach to Signover from EMU 2017 with Chris Hicks

Transition of care is a high-risk event. Signover behavior is a more complicated set of acts than many of us give credit. Here are some tips to improve signover etiquette and to ensure the transfer of information is effective.

Find a “Sterile Cockpit”: Retreat to a less chaotic area. Minimize interruptions. Dedicate these few minutes to signover only.

Involve the entire team: This includes a charge/lead nurse and all the trainees.

Start with most important data: Talk about sickest patients first.

The 3 A’s:

- Administrative issues (this is what’s outstanding),

- Anticipate (best guess on results of tests and disposition),

- Action Items (“this is what you need to do…”)

Close the loop: Receiver recaps the critical data.

Ensure a post signover review is completed in the chart and that the patient is informed of the plan when possible.

Patient Complaints and How to Avoid Them from EMU 2017 with Matt Poyner

Patient complaint themes

Attitude of physician – condescending/negative attitude

Communication issues – not providing basic explanations, orienting to ED processes

Access to care – not getting what they feel entitled to

Quality of care – bad things happened, it’s the doctor’s fault

What patients want

- Explanations and acknowledgement of their suffering

- Assurance that something will change so it won’t happen again

Common pitfalls when responding to patient complaints

Poor preparation/factual errors.

Failure to acknowledge the suffering of the patient.

Defensive rather than reflective tone.

No assurance that effort with be made to improve.

Pearls on how to respond to patient complaints (PAIN Acronym)

PREPARE – study the chart, respond within a week if possible

APOLOGISE – there is always something to apologize for, whether it be for their suffering, that expectations were not met, or especially if an error was made. Apologizing is not admitting responsibility, it is showing empathy and a willingness to find a resolution.

INFORM – explain what you did and why you did it; tell them you care about doing a good job

NEXT STEPS – give assurance that something will be done to improve: extra reading, reviewing the case within your group, M&M rounds

References for Patient Complaints

- Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):213-21.

- Kraman SS, Hamm G. Risk management: extreme honesty may be the best policy. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(12):963-7.

- Mazor KM, Reed GW, Yood RA, Fischer MA, Baril J, Gurwitz JH. Disclosure of medical errors: what factors influence how patients respond?. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):704-10.

- Gallagher TH, Levinson W. Disclosing harmful medical errors to patients: a time for professional action. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(16):1819-24.

- Boothman RC. Apologies and a strong defense at the University of Michigan Health System. Physician Exec. 2006;32(2):7-10.

- Bismark M, Dauer E, Paterson R, Studdert D. Accountability sought by patients following adverse events from medical care: the New Zealand experience. CMAJ. 2006;175(8):889-94.

- Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(22):2565-9.

- Wallace G. How to apologize when disclosing adverse events to patients. CMPA Information Sheet; September 2006 (ISO664E).

Acute Vestibular Syndrome Pitfalls & Fallacies from EMU 2017 with Walter Himmel

Vertigo has been discussed EM Cases before – Episode 6 (Walter Himmel & Dan Selchen) and Episode 45 (Stuart Swadron), but here are some important highlights that will help you in the diagnosis and disposition of acute vestibular syndromes.

Acute vestibular syndrome is defined as continuous vertigo (ie. hours) with nausea, vomiting, movement intolerance and nystagmus. The challenge is to distinguish between the benign peripheral etiology of vestibular neuritis and the serious central etiology of stroke.

Timing is everything. A truly abrupt onset is more likely a stroke or TIA than vestibular neuritis. BPPV presents differently to acute vestibular syndromes, with only one minute of vertigo always triggered by movement, never coming on at rest, with relatively asymptomatic periods in between the episodes of vertigo. All vertigo, no matter what the cause is worsened by movement. The big pitfall is to diagnose BPPV just because the vertigo is worse with movement or when you do a Dix-Hallpike maneuver. BPPV only occurs with movement. If a patient describes a history of lying perfectly still and suddenly gets vertigo, that’s not BPPV.

Even with BPPV, the patient will say that they is constantly “dizzy” whether they move or not. However, after a minute and with no further movement, the vertigo will stop in BPPV. The history may be difficult to analyze. The spinning or delusion of movement will stop. However, the sense of unsteadiness or slight disequilibrium may persist. The important word in the history is “bed.” These patients get a sudden triggering of vertigo when they roll over or lift their head up in bed.

Fallacies of Vertigo

#1: Patients with central vertigo must have at least one of the 5 Ds (Dizziness, Diplopia, Dysarthria, Dysphagia and Dysmetria) or long tract signs.

Stroke may present as isolated vertigo with only minor gait disturbance without any of the 5 Ds or long tract signs.

#2: Unidirectional nystagmus is always a sign of peripheral vertigo.

While unidirectional nystagmus usually points to a peripheral cause, it can occur with central causes of vertigo. Unidirectional nystagmus does not, on it’s own, rule in a peripheral cause. If nystagmus is definitely multidirectional, or purely vertical with no rotatory component the cause is almost certainly central. The HINTS exam can help differentiate a peripheral vs. central cause of acute vestibular syndrome, although this is not perfect

#3: Perform a Dix Hallpike test on every vertigo patient.

- This test is only useful for patients with truly paroxysmal, positional vertigo

- Only perform this on those patients who have a good story for BPPV

- POSITIVE test if 1) onset of vertigo + 2) vertical rotatory nystagmus

- All vertiginous disorders will worsen with movement, regardless of the cause

#4: Young patients do not have strokes.

While strokes are certainly less common in patients <50 years of age, about 1/4 of strokes are caused by vertebral artery dissections in young patients.

High Risk Scenarios in Acute Vestibular Syndrome

Be cautious of the patient with vertigo plus pain.

- Headache – consider plain head CT to rule out a cerebellar hemorrhage

- Neck pain – consider CT angiogram or MR angiogram of the head and neck to rule out vertebral artery dissection (note that not everyone with vertigo needs an angiogram. Angiograms still need to be done selectively based on all the pearls and misconceptions that we’ve just reviewed here)

- 50% of vertebral artery dissections are painless

Discharge diagnosis: vertigo NYD.

- Vertigo is a symptom, not a diagnosis

- If you can’t describe a specific diagnosis, the patient should probably not go home

Can’t ambulate, can’t discharge.

- This rule is true for nearly all emergency department dispositions

- If this is the case, you will certainly need imaging as well as a discussion with your consultants

Dr. Himmel’s detailed handout on vertigo

References for Vertigo

- Tarnutzer MD et al. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? CMAJ 2011;183(9):E571-E591.

- Lee H. Isolated Vascular Vertigo. Journal of Stroke 2014;16(3):124-130.

- Edlow J et al. Using The Physical Examination to Diagnose Patients With Acute Dizziness And Vertigo. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 2016;50(4):617-628.

- Nelson JA et al. The Clinical Differentiation of Cerebellar Infarction from Common Vertigo Syndromes. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 2009;10(4);273-277.

- Newman-Toker D et al. Normal head impulse test differentiates acute cerebellar strokes from vestibular neuritis. Neurology 2008;70:2378-2385.

- Kattah JC et al. HINTS to Diagnose Stroke in the Acute Vestibular Syndrome. Stroke 2009;40:3504-3510.

- Baloh R. Vestibular Neuritis. N Eng J Med 2003;348:1027-32.

- Hotson J et al. Acute Vestibular Syndrome. N Eng Med 1998;339:680-685.

- Kim J et al. Benign Positional Vertigo. N Eng J Med 2014;370(12):1138-1147.

- Parnes L et al. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ 2003;169(7)681-693.

- Robertson J et al. Cervical Artery Dissections: Journal of Emergency Medicine 2016;51(5)508-518.

- Chase M et al. ED patients with vertigo: can we identify clinical factors associated with acute stroke. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2012;30:587-591.

Other FOAMed Resources on Vertigo

EM Lyceum on differentiating peripheral vs central vertigo and imaging decisions

EMCrit on diagnosis of posterior stroke

EMDocs on Posterior circulation strokes

Drs Helman, Hicks, Himmel, Poyner and Sommer have no conflicts of interest to declare

Quote of the month

“Stay hungry, stay young, stay curious, and above all, stay humble because just when you think you got all the answers, is the moment when some bitter twist of fate in the universe will remind you that you very much don’t.”

― Tom Hiddleston

Now Test Your Knowledge:

Leave A Comment