This is EM Cases Episode 116 – Emergency Management of Opioid Misuse, Overdose and Withdrawal

Unless you’ve been living in a hut on an island in the South Pacific, you are certainly aware of the opioid epidemic. Its roots are deep. Its social, medical, and economic considerations are varied and complex. To even the most seasoned EM physician, opioid-addicted, opioid-overdosed, and opioid-withdrawing patients can be a challenge. But by the end of this episode, the discomfort you feel managing these patients will be at least partly dispelled, thanks to Drs. Kathryn Dong, Michelle Klaiman, and Aaron Orkin. They are champions of this complex issue whose management is rapidly evolving, and with them, we’ll unpack the dizzying world of opioids, and help you set in motion the movement that will lead the way to tackle one of the biggest challenges we face in the 21st century. And the beauty of it is that individual treatments don’t have to be complicated. You might be surprised to find that just taking the first step in being part of the solution to the opioid epidemic makes these interactions become more meaningful, satisfying and impactful.

Podcast production, sound design & editing by Anton Helman

Written Summary and blog post by Taryn Lloyd, edited by Anton Helman Oct 2018

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A, Lloyd, T, Klaiman, M, Orkin, A, Dong, K. Emergency Management of Opioid Misuse, Overdose and Withdrawal. Emergency Medicine Cases. October, 2018. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/opioid-misuse-overdose-withdrawal/. Accessed [date].

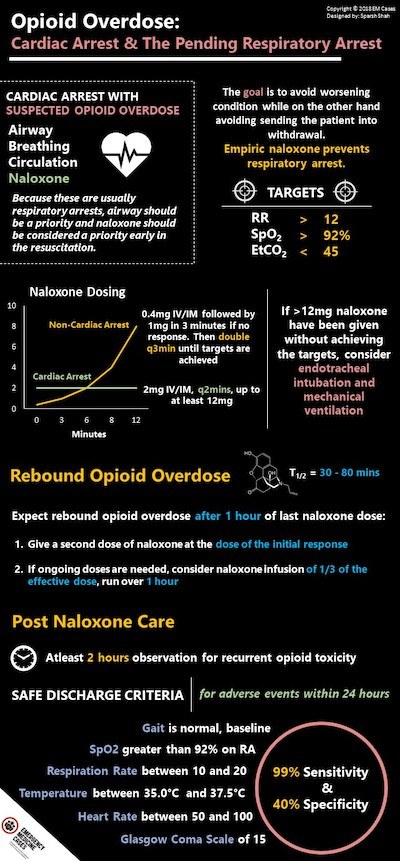

Cardiac arrest in the setting of suspected opioid overdose

While the current trend of priorities in cardiac arrest favour CABC rather than ABC, in the patient suspected of opioid overdose, the priorities should be ABC-N – the ‘N’ standing for Naloxone. Because these are usually respiratory arrests, Airway should be a priority and naloxone should be considered a priority early in the resuscitation.

Naloxone dosing in cardiac arrest:

- 2mg IV or IM

- Repeat dose every 2 minutes, up to at least 12mg

Unclear conditions leading to cardiac arrest?

Still consider high dose naloxone IV or IM given empirically. Consider any potential bias you may have in what a person who uses opioids may look like. Opioid overdose comes in many forms and is not always obvious. Many complex medical patients are on high dose opioids.

Pitfall: A major pitfall is assuming no opioid overdose in the patient with normal or enlarged pupil size. The classic sign of pinpoint pupils is not always present when mixed substances, sometimes without the patient’s awareness of drug mixing or contamination, is at at play.

AHA Guidelines for CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care for Opioid overdose

Opioid overdose: The pending respiratory arrest & decreased LOA

Empiric naloxone prevents respiratory arrest.

Naloxone dosing in non-cardiac arrest opioid overdose

The goal with naloxone administration is to avoid worsening respiratory depression, aspiration and cardiac arrest on the one hand, while on the other hand avoiding sending the patient into severe opioid withdrawal and an agitated state.

Targets of naloxone dosing

- RR>12

- SpO2 >90%

- EtCO2 <45

While traditional teaching suggested 0.04mg IV q3mins until response, with fentanyl analogues, patients often require as much as 12mg of naloxone. Therefore current dosing recommendations are:

First dose: 0.4mg IV/IM followed by 1mg in 3 minutes if no response.

Then double the dose q3mins until targets are reached as outlined above.

If >12mg naloxone have been given without achieving the above targets, consider endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Earlier intubation may be required.

Pitfall: A major pitfall is sending a patient home soon after clinical stability has been achieved with naloxone. Most opioids last longer than naloxone. It is therefore imperative to observe opioid overdose patients for at least 2 hours after targets have been achieved with naloxone. With naloxone having a short half-life (30-80 mins), the discharged patient could suffer a rebound overdose that could be fatal.

The half life of naloxone ranges from 30-80 minutes depending on liver function. Expect rebound opioid overdose about 1 hour after naloxone was given.

Redosing naloxone in the patient with rebound opioid overdose

Give a second dose of naloxone at the dose given for response initially.

If ongoing doses are needed, consider naloxone infusion:

1/3 of the effective naloxone dose given, run over 1 hour.

What are the potential harms of giving naloxone?

If naloxone is overdosed, it can cause opioid withdrawal, which is almost never fatal but is very uncomfortable for the patient. While pulmonary edema is recognized as a side effect of naloxone, it is rare and may be due to other co-morbid factors in the opioid overdose patient.

When is it safe to discharge an opioid overdose patient after naloxone?

Post-naloxone Care:

Observe patients for at least 2 hours after the last dose of naloxone was given to assess for recurrent opioid toxicity. Reassess for sedation, respiratory depression, medical complications of overdose and/or drug use (aspiration, pulmonary edema, rhabdomyolysis, compartment syndrome, infections).

A clinical prediction tool was developed in 2000 in a study of 573 patients. Patients with presumed opioid overdose were safely discharged one hour after naloxone administration if they had:

- Their baseline gait

- Oxygen saturation on room air of >92%

- Respiratory rate >10 breaths/min and <20 breaths/min

- Temperature of >35.0 degrees C and <37.5 degrees C

- Heart rate >50 beats/min and <100 beats/min

- GCS = 15.

The rule had a 99% sensitivity and 40% specificity for adverse events within 24 hours.

Pitfall: Avoid the temptation to order “discharge when awake and ambulating safely”. This may lead to a fatal rebound opioid overdose and is a missed opportunity for Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) which has potential to save lives and improve functional outcomes (see SBIRT discussion below).

Emergency Management of Opioid Withdrawal

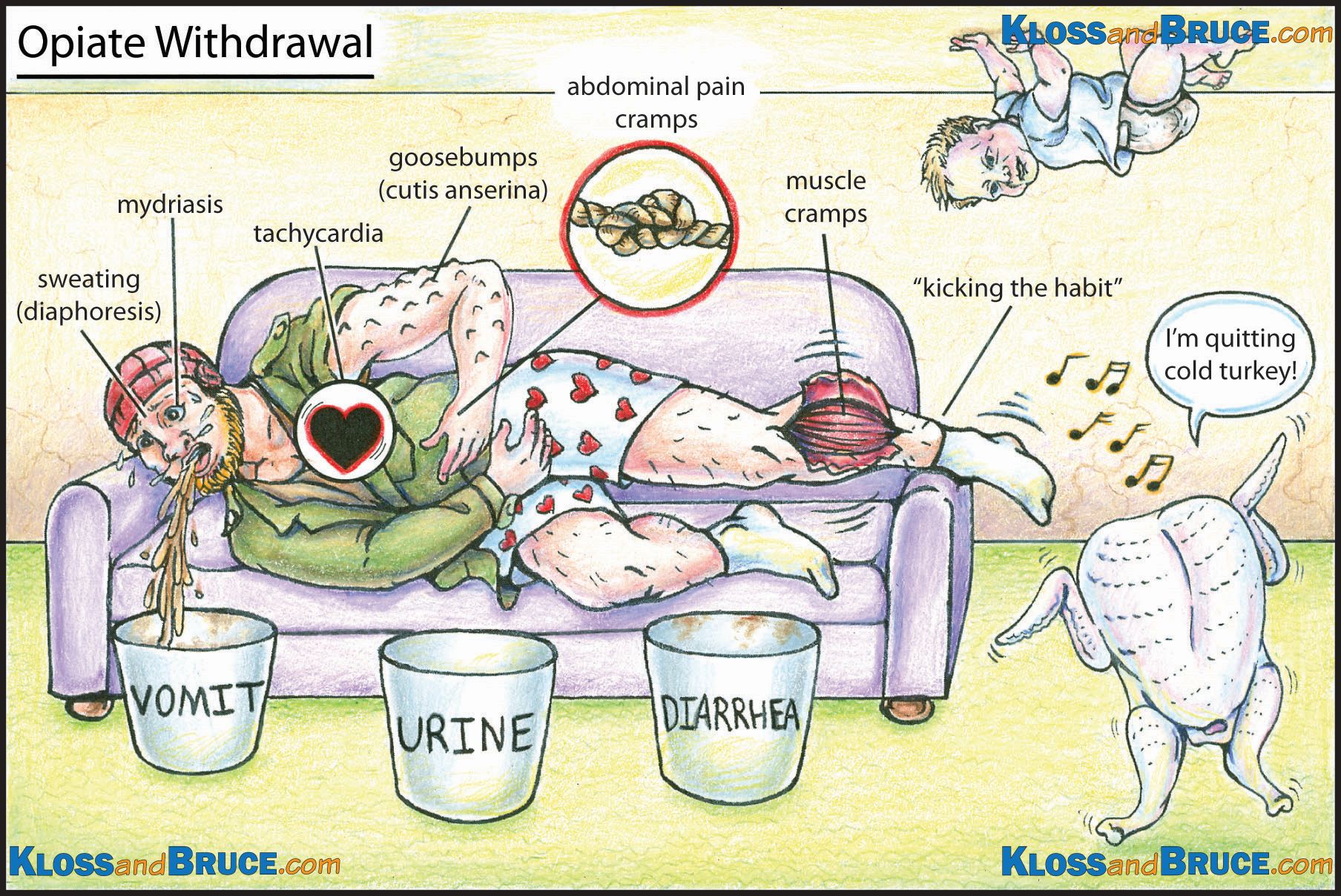

The clinical features of opioid withdrawal overlap with severe gastroenteritis.

Care of Life in the Fast Lane

Opioid withdrawal is rarely life threatening, however it may precipitate preterm labor in pregnant patients, ACS in patients with coronary artery disease and there are published case reports of temporally related Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

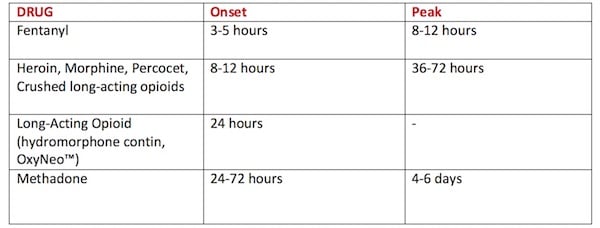

Expected onset and peak of opioid withdrawal by drug

Even after just 5 days of taking an opioid, physical and psychological withdrawal symptoms may develop upon cessation. Consider this when prescribing opioids on discharge from the ED and counsel patients appropriately.

5 Steps to ED Opioid Withdrawal Management

- Does the patient meet criteria for opioid use disorder?

- Assess readiness to quit opioids.

- Assess severity of withdrawal using COWS.

- Administer Buprenorphine-Naloxone (Suboxone™) for patients who fulfill criteria OR treat symptoms of withdrawal for those who do not fulfill criteria for Buprenorphine-Naloxone initiation.

- Counsel and arrange appropriate follow-up

Step 1 of ED opioid withdrawal management: Does the patient meet criteria for opioid use disorder?

Step 2: Assess readiness to quit opioids

What are the goals of the patient? Are they ready and willing to start treatment in hopes of stopping their opioid use?

Use the “Readiness Ruler” to assess stage of change: On a scale of 1-10, how ready are you to make a change today? Ask “Where do you want to go from here?” and “What would make tomorrow better than today?”. Build on their past successes; any positive changes. Describe the discrepancy between current behaviors and their goals.

Obtain informed consent for starting Suboxone™ (buprenorphine/naloxone) in the ED for their opioid use disorder. If they are not interested in starting Suboxone™, using a patient-centered approach, gently share your concerns about their ongoing opioid use, the risk of overdose and medical complications, and harm reduction techniques (naloxone kit, clean needles and supplies).

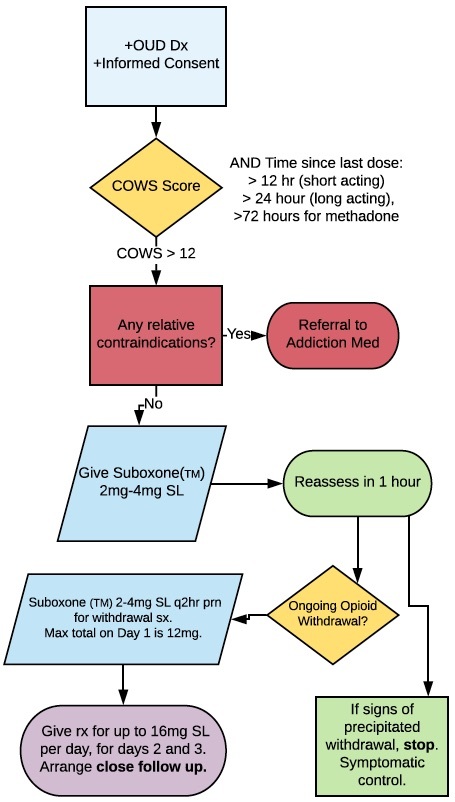

Step 3: Assess the severity of opioid withdrawal using COWS

Use the validated assessment tool, the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS) to determine the severity of withdrawal. This scale is similar to the CIWA scale used for alcohol withdrawal and is easily administered by ED staff. Points are assigned for the various symptoms and signs of withdrawal (tachycardia, sweating, restlessness, enlarged pupils size, bone/joint aches, runny nose/tearing, GI upset, tremor, yawning, anxiety/irritability, and “gooseflesh” skin).

A score of 5-12 = mild; 13-24 = moderate; 25-36 = moderately severe; greater than 36 = severe.

Patients must score at least in the moderate range (>12) to be eligible for Buprenorphine-Naloxone therapy.

Step 4: Buprenorphine-Naloxone and treatment of withdrawal symptoms

Prerequisites for starting Suboxone in the ED:

- Patient has an opioid use disorder (OUD)

- Patient gives informed consent

- COWS is >12, AND

- Time since last opioid >12hr (short acting), >24hr (long acting), >72hr (methadone)

OUD = Opioid Use Disorder, COWS = Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Score, Suboxone is brand name for Buprenorphine-Naloxone

Dosing Buprenorphine-Naloxone (Suboxone™)

Buprenorphine-Naloxone 2mg/0.5mg x 1-2 tabs SL repeated in 1-2hrs for ongoing withdrawal symptoms; max 12mg.

Suboxone™ is buprenorphine and naloxone in a sublingual tablet. Naloxone is not active unless injected; it is a taper-resistance medication. The Buprenorphine component of Suboxone™ is a partial agonist that acts on the opioid mu receptor, it has a high binding affinity but only partial intrinsic activity on the receptor (enough for pain and withdrawal but with less risk of respiratory depression and side effects). Compared to heroin, it binds stronger, but it is not as activating.

There is moderate evidence to suggest that Buprenorphine-Naloxone decreases mortality, improves withdrawal symptoms, decreases drug use, improves follow-up rates and decreases crime rates.

Example of ED Buprenorphine-Naloxone order set

Relative Contraindications to ED Buprenorphine-Naloxone Initiation

- Allergy to either buprenorphine or naloxone

- Hepatic dysfunction

- Respiratory distress currently

- Decreased LOC currently

- Concurrent active alcohol use disorder

- Concurrent benzodiazepine use

Learn more about Buprenorphine in the ED in EMU 365: Expanding Our Scope- ED Initiated Buprenorphine

Treatment of opioid withdrawal symptoms for those who do not fulfill criteria for Buprenorphine-Naloxone

If the patient either does not meet criteria for opioid use disorder, or does not want to start Buprenorphine-Naloxone, counsel them regarding their risks and provide symptomatic relief for withdrawal symptoms. Even brief counselling and referral to follow-up services (i.e. drop in clinics, addiction medicine teams, harm reduction centers in the community) has been shown to lead to 37-45% patient engagement in treatment at 30 days.

For bone/joint pain: NSAIDs, IV or Oral +/- Acetaminophen; given the high toxicity of illicit opioids, consider a small, controlled prescription for short-acting opioid. Fax the prescription to the pharmacy and consider daily dispensed or observed dosing in the pharmacy until they can see appropriate follow up.

For tachycardia, hypertension, sweating, anxiety and restlessness: Clonidine (beware hypotension- learn more about clonidine toxicity in EM Quick Hits 8 (skip to 06:20))

For nausea/vomiting: Ondansetron (beware prolonged QT in patients taking methadone)

Pitfall: A common pitfall is giving benzodiazepines for symptoms associated with opioid withdrawal. Benzodiazepines in this setting portend a very high risk for respiratory depression in overdose if the patient relapses, as well as a high likelihood when the patient is in uncomfortable withdrawal. Use caution when treating alcohol withdrawal and opioid withdrawal in tandem and consider consultation with an addiction specialist.

Take Home Buprenorphine-Naloxone Initiation from the ED

If the patient has good insight into the level of their withdrawal symptoms (i.e. the reported severity correlates with the COWS score) and they aren’t meeting criteria to start in the ED, consider having them go home with Buprenorphine-Naloxone doses to start at home once they are in significant, moderate-severe, withdrawal.

Set up a tight referral pathway for rapid follow-up of suboxone starts. A patient should be seen in a rapid access addiction medicine clinic or similar community clinic the next 1-2 days as possible. Provide a prescription for daily observed dosing in pharmacy, at the appropriate dose up to 16mg SL per day until follow up.

Pain Control for Patients on Buprenorphine-Naloxone

- Maximize non-opioid therapies, NSAIDs, Acetaminophen

- Do not stop buprenorphine or lower buprenorphine dose (this is high risk for relapse!)

- Buprenorphine-Naloxone dosing may be split BID or TID for pain control

Step 5: Counsel and arrange appropriate follow-up

Counselling the opioid use disorder patient

You can save a life by choosing to intervene on patients that present for other issues related to substance use – post-trauma, psychiatric, found down “intoxicated.”

Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is an excellent way to make a difference for this large subset of patients we see in the emergency department. Even without starting medication, 37-45% of patients in one study that underwent SBIRT in the ED, engaged with treatment at 30 days.

Ask for permission to discuss substance use and overdose, to discuss goals, and to express your concerns with their current use.

- Screen for other substance use (see below)

- Screen for safety (the opioid overdose could be a suicide attempt!)

- Assess the goals of the patient, and stage of change

- Offer referral to resources in community or hospital appropriately around goals (i.e. housing, detox, addiction medicine clinic, family doctor services, safe injection facilities)

- Discuss and offer naloxone kits, clean injection supplies

- Counsel around high risk of accidental overdose given withdrawal and/or decrease in tolerance

Pitfall: Sending an opioid patient directly to a detoxification center who is not psychologically ready to quit opioids can have devastating consequences. If the patient is not ready, do not push or force the patient to attend detox. Going to detox can put them at increased risk for overdose if they leave prematurely and relapse, given the decrease in their tolerance. Be sure to counsel your patient around this overdose risk.

Screening for alcohol and opioid use disorder

Use validated tools tools such as the CAGE questionnaire. An even briefer screening tool has only 2 questions:

“In the past year, how often have you drank 5 or more drinks per day?”

“Have you used prescription drugs for non-medical purposes or illegal drugs within the last year?”

Brief Intervention: Brief negotiated interview

- Build rapport, ask permission to discuss substance use and goals

- Open ended questions, non-judgmental

- Give feedback and share concern if patient gives permission

- Identify the problem and your concern, and tie it to ED presentation

- Use the “Readiness Ruler” to assess stage of change

- On a scale of 1-10, how ready are you to make a change today?

- “Where do you want to go from here?”

- “What would make tomorrow better than today?”

- Build on their past successes, any positive changes

- Develop discrepancy between current behaviors and their goals

- Avoid arguing, telling them what to do. Instead roll with resistance.

- Avoid stigmatizing language: getting “clean”, addict, junkie

Learn more about opioid misuse in Episode 74: Opioid Misuse in Emergency Medicine

Why not use methadone for opioid withdrawal in the ED?

Despite Health Canada lifting the exemption needed to prescribe methadone, provincial requirements will vary and EM physicians should proceed carefully with any prescribing. There is no role for ED methadone initiation. The only role for giving methadone in the ED is for a patient who has been clinically stable on methadone, with a good reason to be missing one or two doses (i.e. clearly in custody of police, or in hospital) with a well documented dose history and stable dose amount. If 3 or more days consecutively of methadone have been missed, a dose adjustment is necessary and they are not considered stable on their dose. Proceed with caution.

Precipitated opioid withdrawal

What is precipitated withdrawal?

Precipitated withdrawal is a relative decrease in the activity at the opioid receptor due to Buprenorphine-Naloxone kicking off any opioid currently bound, but not activating the receptor as well. The patient will feel sudden worsening of their withdrawal symptoms within 30 minutes of their first Buprenorphine-Naloxone dose. Timing is key. Buprenorphine-Naloxone must be at least 12 hours since any short acting opioid, 24 hours for any long acting opioid, and at least 72 hours from any methadone.

How do I treat precipitated withdrawal?

This is very difficult to treat and can often dissuade the patient from continuing with opioid agonist therapy. Do not treat with escalating doses of opioids to overcome the buprenorphine (dangerous for overdose). It is also not always effective to keep escalating the Buprenorphine-Naloxone dosing. In most cases, treat symptomatically and wait until 24 hours to restart. Consider specialty consultation and follow up if available.

All patients are more than their addiction.

We have a significant opportunity to improve the lives patients with opioid use disorders in the long run within the walls of the emergency department.

Key Take home points for Opioid Misuse, Overdose and Withdrawal

- Total naloxone dose of more than 12mg is sometimes required for opioid overdose treatment, especially for fentanyl analogues.

- The absence of pinpoint pupils does not rule out opioid overdose.

- Observe patients for at least 2 hours after the last dose of naloxone and use the clinical prediction tool for disposition decisions; avoid “discharge when awake and ambulating safely”.

- The clinical features of opioid withdrawal overlap with severe gastroenteritis.

- Withdrawal symptoms can develop after only 5 days of taking an opioid.

- Avoid benzodiazepines in the treatment of opioid withdrawal.

- Be sure that your patient fulfills the criteria for opioid use disorder before starting Suboxone in the ED.

- A COWS score >12 is an important prerequisite for prescribing Buprenorphine-Naloxone to avoid precipitated withdrawal.

- The ED dose of Buprenorphine-Naloxone (Suboxone) is 2mg/0.5mg x 1-2 tabs SL repeated in 1-2hrs for ongoing withdrawal symptoms; max 12mg.

- SBIRT – Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment has been shown to increase the rates of engagement in treatment at 30 days.

- Avoid discharge to a detoxification center for opioid use disorder patients who are not ready to stop opioids.

- There is no role for ED methadone initiation.

For more on opioids on EM cases:

Episode 27: Drugs of Abuse – Stimulants and Opiates

Episode 74 Opioid Misuse in Emergency Medicine

Best Case Ever 41 Opiate Misuse and Physician Compassion

Best Case Ever 12: Drugs of Abuse

BCE 76 Opioid Withdrawal

References

- Wermeling DP. Review of naloxone safety for opioid overdose: practical considerations for new technology and expanded public access. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2015;6(1):20-31.

- Christenson J, Etherington J, Grafstein E, et al. Early discharge of patients with presumed opioid overdose: development of a clinical prediction rule. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(10):1110-8.

- https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/apparent-opioid-related-deaths-report-2016.htmlhttps://www.theopioidchapters.com/

- Agerwala, S. M., & McCance-Katz, E. F. (2012). Integrating Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) into Clinical Practice Settings: A Brief Review. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 44(4), 307–317.

- Albertson, Timothy E., et al. “TOX-ACLS: Toxicologic-Oriented Advanced Cardiac Life Support.” Annals of Emergency Medicine, vol. 37, no. 4, 2001, doi:10.1067/mem.2001.114174.

- Buprenorphine/Naloxone for Opioid Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline, CAMH, Handford et al., 2011.

- Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550.

- Molero Y, Zetterqvist J, Binswanger IA, Hellner C, Larsson H, Fazel S. Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders and Risk of Suicidal Behavior, Accidental Overdoses, and Crime. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;:appiajp201817101112.

- Champassak, S. L., Miller, M., & Goggin, K. (2015). Motivational interviewing for adolescents in the emergency department. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 16(2), 102-112. doi:10.1016/j.cpem.2015.04.004

- Chang AK et al. Effect of Single Dose of Oral Opioid and Nonopioid analgesics on Acute Extremity Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017.

- D’Onofrio, G., Chawarski, M.C., O’Connor, P.G. et al. J GEN INTERN MED (2017) 32: 660. https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1007/s11606-017-3993-2

- D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency Department–Initiated Buprenorphine/Naloxone Treatment for Opioid DependenceA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636–1644. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3474

- D’Onofrio, G., Pantalon, M. V., Degutis, L. C., Fiellin, D. A., & O’Connor, P. G. (2005). Development and implementation of an emergency Practitioner–Performed brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine, 12(3), 249-256. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2004.10.021

- Farnia MR et al. Comparison of Intranasal Ketamine Versus IV Morphine in Reducing Pain in Patients with Renal Colic. Am J Emerg Med 2017. PMID: 27931762

- Goldfrank L, Weisman RS, Errick JK, Lo MW. A dosing nomogram for continuous infusion intravenous naloxone. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(5):566–70.

- Gowing L, Ali R, White JM, Mbewe D. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD002025. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002025.pub5.

- Jutras‐Aswad, D., Widlitz, M., & Scimeca, M. M. (2012). Treatment of buprenorphine precipitated withdrawal: A case report. The American Journal on Addictions, 21(5), 492-493. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00262.

- Kerensky, Todd, and Alexander Y. Walley. “Opioid Overdose Prevention and Naloxone Rescue Kits: What We Know and What We Don’t Know.” Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, vol. 12, no. 1, July 2017, doi:10.1186/s13722-016-0068-3.

- Madras, B. K., Compton, W. M., Avula, D., Stegbauer, T., Stein, J. B., & Clark, H. W. (2009). Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: Comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 99(1-3), 280-295. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003

- McGinnes, R. A., Hutton, J. E., Weiland, T. J., Fatovich, D. M., and Egerton‐Warburton, D. (2016) Review article: Effectiveness of ultra‐brief interventions in the emergency department to reduce alcohol consumption: A systematic review. Emergency Medicine Australasia, doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12624.

- Molero Y et al. Medications for Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders and Risk of Suicidal Behavior, Accidental Overdoses, and Crime. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;:appiajp201817101112.

- Steele, A., & Cunningham, P. (2012). A comparison of suboxone and clonidine treatment outcomes in opiate detoxification. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 26(4), 316-323. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2011.10.006

- Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs 2003; 35:253.

Drs. Helman, Dong, Klaiman and Orkin have no conflicts of interest to declare

Other FOAMed Resources on opioid misuse, overdose and withdrawal

EM Cases Episode 74 Opioid Misuse in EM with David Juurlink and Reuben Strayer

Reuben Strayer on ED Initiation of Buprenorphine Pathway

Reuben Strayer on Emergency Care in an Epidemic Treatment Map

R.E.B.E.L. EM on Do patients with opioid dependence benefit from buprenorphine-naloxone treatment initiation in the ED

The SGEM on Discharge after Heroine Overdose

Opioid Prescribing Guidelines for the ED on StopOpioid

Now test your knowledge with a quiz.

I don’t have experience with prescribing Suboxone and really appreciated all the resources and background.

I suggest a different approach to opioid toxicity, however. If the cardiac arrest was caused by opioid toxicity, then apnea lead to hypoxia and secondary cardiac arrest; opioids would not have a direct cardiotoxic effect. Naloxone can reverse apnea before cardiac arrest occurs, but wouldn’t reverse cardiac arrest. Thus, focusing on quality CPR is paramount to survival and naloxone administration may only distract from the cardiac arrest management.

ILCOR, AHA, and HSFC concluded that naloxone has not shown benefit in reversing cardiac arrest. However, they do recommended that lay rescuers can start CPR and then administer naloxone as lay rescuers may not be able to tell the difference between cardiac arrest and respiratory arrest with unconsciousness.

The 2015 AHA/HSFC guidelines indicated: “While it is not expected that naloxone is beneficial in cardiac arrest, whether or not the cause is opioid overdose, it is recognized that it may be difficult to distinguish cardiac arrest from severe respiratory depression in victims of opioid overdose. While there is no evidence that administration of naloxone will help a patient in cardiac arrest, the provision of naloxone may help an unresponsive patient with severe respiratory depression who only appears to be in cardiac arrest (ie, it is difficult to determine if a pulse is present).”

Additionally, it is unlikely that fentanyl or carfentanyl toxicity requires more that the usual doses of naloxone. The reports of using large doses primarily come from lay rescuers, patients with suspected mixed toxicity, and patients who have already sustained brain anoxia. Remember that naloxone can lead to a brief increase in consciousness in conditions other than opioid toxicity (eg: CNS disasters). Naloxone dosing (up to 1 mg) is sufficient to displace opioids enough to allow some respiratory function in all but the most massive overdoses. Failure to respond to the initial dosing, should lead to supporting ventilation and looking for other causes. Since the half-life of naloxone is short (20-60 minutes), it may require an infusion if the initial response was positive in a large overdose.

The length of observation after opioid toxicity should be directly linked to the presumed cause and possible dose taken (larger doses or naloxone required may indicate a larger dose of opioid taken). While the studies of short-observations being safe are consistent, they are largely from the heroin era (short-acting), and don’t reflect the much-longer observation time needed for large fentanyl toxicity (often require reducing of naloxone at 1-2 hours), and/or methadone (half-life of > 20 hours in toxic dosing).

This article is a great resource on the pharmacology of naloxone and carfentanil (potent opioid): Cole JB, Nelson LS. Controversies and carfentanil: We have much to learn about the present state of opioid poisoning. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 Nov;35(11):1743–5.

Thanks Michelle for your insights. In the podcast we agree with almost everything you’ve pointed out except the dosing of naloxone. Our recommendations for high dose naloxone come from Ontario Poison Control, and mixed and massive overdoses are not infrequent occurrences that may require large doses. With little downside to naloxone, it’s better to err on the side large doses. With regard to observation times we are also in agreement and pointed out in the podcast that observation times will also depend on the opioid taken in addition to the “minimum 2hr rule” and the Christensen decision tool. BTW the 2015 AHA paragraph that you’re quoting was written by Dr. Orkin who was the guest expert on the podcast and he explained the lack of evidence for benefit of naloxone in cardiac arrest. I think the key point is that it is sometimes difficult to know for certainty if a patient is in true cardiac arrest or not. No pulse palpated does not necessarily mean cardiac arrest. Many patients presumed to be in cardiac arrest with opioid overdose may not be and in those cases, naloxone is very likely to be beneficial.

I wanted to respond to Dr. Welsford’s very insightful comments. Thanks for listening to the podcast and posting these comments.

Quality CPR is indeed the priority in cardiac arrest (especially compressions), and I would not want to suggest otherwise. The relevant passage from the full-text version of the AHA/HSFC guidelines is here:

>>”ACLS Modification: Administration of Naloxone

>>Respiratory Arrest

ACLS providers should support ventilation and administer naloxone to patients with a perfusing cardiac rhythm and opioid-associated respiratory arrest or severe respiratory depression. Bag-mask ventilation should be maintained until spontaneous breathing returns, and standard ACLS measures should continue if return of spontaneous breathing does not occur (Class I, LOE C-LD).

>>Cardiac Arrest

We can make no recommendation regarding the administration of naloxone in confirmed opioid-associated cardiac arrest. Patients with opioid-associated cardiac arrest are managed in accordance with standard ACLS practices.

>>Observation and Post-Resuscitation Care

After ROSC or return of spontaneous breathing, patients should be observed in a healthcare setting until the risk of recurrent opioid toxicity is low and the patient’s level of consciousness and vital signs have normalized (Class I, LOE C-LD). If recurrent opioid toxicity develops, repeated small doses or an infusion of naloxone can be beneficial in healthcare settings (Class IIa, LOE C-LD).

>>Patients who respond to naloxone administration may develop recurrent CNS and/or respiratory depression. Although abbreviated observation periods may be adequate for patients with fentanyl, morphine, or heroin overdose, longer periods of observation may be required to safely discharge a patient with life-threatening overdose of a long-acting or sustained-release opioid.

>>Naloxone administration in post–cardiac arrest care may be considered in order to achieve the specific therapeutic goals of reversing the effects of long-acting opioids (Class IIb, LOE C-EO).”

The key concept here is that there are no modifications to standard ACLS practices in confirmed opioid-related cardiac arrest. However, we should be aware that differentiating severe respiratory arrest (peri-cardiac arrest) from “true” cardiac arrest in these patients can be difficult. Cardiac arrest can be a tough diagnosis in patients who would otherwise have a RR of 6 and a very thready often unpalpable pulse. There isn’t time to make that diagnosis conclusively. (Some of the prehospital cardiac arrest literature in this population makes that clear — cases that are thought to be in cardiac arrest resolve far too quickly and completely to have been true arrest, and likely had very slow pulses that were difficult to detect promptly.) As a result, it is reasonable to initiate care in these cases promptly with suspicion that the victim may not be in true cardiac arrest and administer naloxone empirically. This is a change from the 2010 guidelines, where the discussion basically stated that there was no evidence to support naloxone administration in cardiac arrest. The 2015 guidelines moved forward by emphasizing that although there is no specific evidence in confirmed cardiac arrest, it may be reasonable to administer naloxone empirically because cardiac arrest is tough to diagnose. We discussed this in the podcast, emphasizing that EPs should know that naloxone is being administered not to treat cardiac arrest, but to address the possibility that the patient is not in cardiac arrest.

I also agree that lay rescuers should start CPR and administer naloxone. However, we should be aware that the literature on pulse checks in unresponsive victims (like severe overdose) have been shown to be ineffective for both laypeople and healthcare providers. We didn’t really get into this in the podcast (or the AHA/HSFC guidelines, frankly), but EPs need to be ready to act logically and empirically knowing that their ability to diagnose cardiac arrest with nothing but their physical exam and a cardiac monitor is severely limited in a severe overdose patient.

The AHA/HSFC guidelines passage above also provides some recommendation on time of discharge and observation.

Finally, it is always critical to consider other causes of cardiac arrest. The escalating naloxone dosing comes from Ontario Poison Control. Emerging severe cases requiring massive naloxone doses help to show just how hard it can be to diagnose cardiac arrest, especially in the first few minutes of a resuscitation.