This is Pediatric Trauma on EM Cases.

Management of the pediatric trauma patient is challenging regardless of where you work. In this EM Cases episode, with the help of two leading pediatric trauma experts, Dr. Sue Beno from Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto and Dr. Fuad Alnaji from Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa we answer such questions as: what are the most important physiologic and anatomic differences between children and adults that are key to managing the trauma patient? How much fluid should be given prior to blood products? What is the role of POCUS in abdominal trauma? Which patients require abdominal CT? How do you clear the pediatric c-spine? Are atropine and fentanyl recommended as pre-induction agents in the pediatric trauma patient? How can the BIG score help us prognosticate? Is tranexamic acid recommended in early pediatric trauma like it is in adults? Is the Pediatric Trauma Score helpful in deciding which patients should be transferred to a trauma center? and many more…

Podcast production & sound design by Anton Helman. Voice editing by Richard Huang. Written Summary and blog post by Shaun Mehta & Alex Hart, edited by Anton Helman May, 2017.

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A, Beno, S, Alnaji, F. Pediatric Trauma. Emergency Medicine Cases. May, 2017. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/episode-99-highlights-emu-2017/. Accessed [date].

Common pitfalls leading to bad pediatric trauma outcomes

Failure to:

Manage the airway – indicated for almost all severe TBI, any hypoxia

Appreciate and treat shock – do not wait for hypotension which is a sign of pre-arrest

Prioritize management of injuries – see “CABC” below

Check bedside sugar if altered LOC – ABCDEFG “Don’t Ever Forget the Glucose”

Keep the child warm

Preparation before the pediatric trauma patient arrives

Use a Broselow tape to draw up all anticipated medications in advance of patient arrival: ketamine 2mg/kg or etomidate 0.3mg/kg, rocuronium 1mg/kg or succinylcholine 1-2mg/kg, fentanyl 2-5mcg/kg, atropine 0.02 mg/kg etc., and to size airway equipment (have one size larger and one size smaller ready as well).

Venous access: Prime lines, have IOs ready, central line kit.

Warm the room, turn on the overhead warmer (for infants) or Bair hugger (for older children), warm crystalloids, set the rapid infuser.

Have pelvic binder or sheet laid out on stretcher with clamps ready.

Team huddle: see Andrew Petrosoniak’s approach to team-based preparation for a critical event

PRIMARY SURVEY PEARLS

C-A-B-C: A new paradigm in pediatric trauma

ATLS has revently moved from the ABC approach to the CAB for trauma resuscitation. Our experts suggest the “CABC” approach: First, identify any catastrophic bleeding, then move on to airway and breathing with a plan to return to circulation assessment.

In general, respect the range of vital signs in the pediatric population. 90th percentile normal pediatric vital signs HERE

Disability: AVPU (Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive) is adequate. Pediatric GCS is also acceptable but not always practical as it is difficult to remember.

Exposure: Important in any trauma patient, but keep in mind increased heat loss in children

Family Presence: Evidence suggests that family presence reduces stress on families and the patient without compromising team dynamics or medical care.

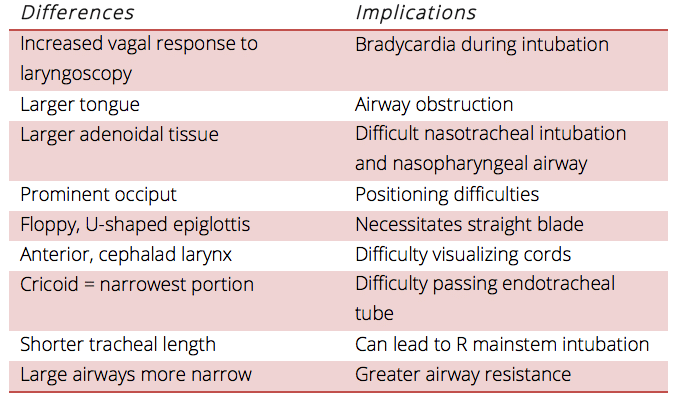

Considerations in pediatric trauma airway

Adapted from Rosen’s Emergency Medicine 8th edition

Pediatric Trauma Airway: 3 P’s

Patency – use an oral airway to prevent obstruction by the tongue, suction any blood, secretions, foreign bodies

Position – towel under torso, occiput on bed

Protection – cuffed ETT (age/4 + 3.5) in all trauma patients

Airway management positioning with either an occipital well or elevating the torso to prevent flexion of the neck caused by the large pediatric occiput.

RSI pearls and pitfalls in Pediatric Trauma

PEARLS

Use a straight blade laryngoscope: Children have a floppy, U-shaped epiglottis which is easier to pick up to allow a view of the vocal cords with a straight blade, especially during c-spine immobilization.

Have your weight based drugs drawn up in advance

Pre-induction: Consider atropine 0.02 mg/kg (minimum 0.1 mg, maximum 0.5 mg) in patients <1 year of age and have it drawn up in case of bradycardic response to intubation in older patients. Consider fentanyl 2-5 mcg/kg 3-5 minutes prior in the head-injured patient to blunt the rise in ICP secondary to intubation.

Update 2022: An observational study using data from 2 national airway consortiums including 1,412 emergency pediatric intubations found that video-assisted laryngoscopy was associated with higher odds of first-attempt success (OR 2.01) and 30% reduced odds of experiencing severe adverse airway outcomes. Abstract

PITFALLS

Inadequate pre-oxygenation time: Children have lower functional residual capacity and shorter apnea times, so consideration should be given to a modified RSI with apneic oxygenation/NIPPV.

Consider early NG tube placement for stomach decompression to allow for full diaphragmatic excursion.

Right mainstem endobronchial intubation: Children have a relatively shorter trachea compared to adults and advancing the ETT too far is not uncommon. A rule of thumb to estimate accurate depth of ETT placement: 3 x tube size

Cricoid pressure: 2 lbs of force can occlude the pediatric airway, so cricoid pressure is not recommended. Instead, to help improve your view consider external laryngeal manipulation (ELM).

Overbagging: To prevent barotrauma all pediatric BVM units should be equipped with a safety pop-off valve along with a manometer, which limits peak inspiratory pressures between 35 and 40 cm H20 per breath. Each breath should be just enough to make chest rise and no more. Counting out loud or using a metronome for accurate rate of bagging can prevent our natural tendency to overbag in stressful situations.

A large randomized prehospital trial out of JAMA in 2000 suggests that the addition of endotracheal intubation to non-invasive ventilation does not improve mortality or neurologic outcome unless prolonged transport times are anticipated.

Shock in Pediatric Trauma

Early recognition of shock is essential in the pediatric polytrauma patient. Look for secondary signs which are often present while the patient is still normotensive (compensated shock). Hypovolemia is the most common cause of shock, with tachycardia being the first manifestation. Other manifestations include narrow pulse pressure, skin mottling, delayed capillary refill, cool extremities and altered mental status. Blood pressure is maintained until 30-40% blood loss due to great cardiac reserve, and so hypotension is an ominous sign (decompensated shock).

Volume Resuscitation

PALS recommends early IO placement (after 90 seconds or 2 attempts at IV placement). The maximum flow rate is usually around 25 mL/min. The IO is temporary; get a large peripheral IV or central access once adequately resuscitated.

How much crystalloid before blood?

While this a controversial topic, our experts suggest that 10-40 ml/kg of warmed crystalloid prior to blood is reasonable in pediatric polytrauma patients in compensated shock, but that early administration of blood components is vital in patients who present in decompensated shock. The principle of permissive hypotension in adult trauma can only be applied to adolescent pediatric patient and is not recommended in younger pediatric patients.

Update 2022: A retrospective cohort study of 287 pediatric trauma patients (aged 0-17) at a level 1 urban trauma center identified a critical administration threshold of >20mL/kg for activating massive transfusion protocols. Beyond this threshold, children were at significantly higher risk for mortality, functional disability at discharge, and required more transfusions. Abstract

From Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2015

Update 2017: A recent retrospective analysis found that in combat-injured children undergoing a massive transfusion, a high ratio of PLAS/PRBC was not associated with improved survival. Abstract

PEDIATRIC TRAUMA SECONDARY SURVEY

Pediatric Severe Head Injury

Brain injury is the leading cause of death in pediatric polytrauma. Severe head trauma is defined as a GCS < 8 or if the patient is only responsive to pain or worse on AVPU. The goal in pediatric severe head injury is to prevent secondary brain injury, minimize raised ICP, and maintain cerebral perfusion pressure.

There are 5 parameters that must be aggressively avoided in the pediatric patient with severe head injury:

- Hypotension – maintain normal SBP and euvolemia

- Hypoxia – maintain SaO2 > 90% and PaCO2 35-40mmHg

- Hypothermia – warmed crystalloid and blood, warmed room, overhead warmer or Bair hugger

- Hypoglycemia – the DEFG in ABCDEFG stands for “Don’t Ever Forget the Glucose”

- Raised ICP – keep head of bed at 30 degrees, remove collar, pain and anxiety control, treat seizures aggressively, normocapnea

For the patient with signs of brain herniation, our experts recommend hyperventilating to a target of pupillary response of constriction and administering 3% hypertonic saline 3-4mL/kg boluses followed by an infusion in addition to the above, until the patient arrives in the O.R.

For minor and moderate head injury use the PECARN head injury decision instrument (PECARN on MD calc)

Dr. Beno’s Best Case Ever on Traumatic Pediatric Cerebral Herniation

Clearing the Pediatric C-spine

The incidence of pediatric c-spine injury in polytrauma patients is <2% with the vast majority of injuries at C1-C3. Clearing the pediatric c-spine is complicated by the higher likelihood of having an unreliable exam and radiation concerns.

Clearing the C spine is age dependent

Reliable exam in >3 years old: Combination of NEXUS and Canadian C-spine Rules

Awake and alert with GCS = 15

Meets NEXUS criteria:

- no midline cervical spine tenderness

- no focal neurologic deficit

- normal alertness

- no intoxication

- no painful, distracting injury

AND moves head in flexion/extension

AND rotate 45 degrees to both sides with no pain

Reliable exam <3 years old: Clinical exam

Unreliable exam < 3 years old: Clinical decision instrument from multicenter study of 12,537 patients in 2009

Four independent predictors of c-spine injury were identified:

- GCS <14 (3 points)

- GCSEYE= 1 (2 points)

- MVC (2 points)

- Age 2 years or older (1 point)

A score of <2 had a negative predictive value of 99.93% in ruling out c-spine injury and were eligable for c-spine clearance without imaging.

For an algorithm on clearing the pediatric c-spine go to TRAUMA ASSOCIATION OF CANADA (TAC) NATIONAL PEDIATRIC C-SPINE EVALUATION PATHWAY: RELIABLE CLINICAL EXAM

Since the vast majority of pediatric c-spine injuries occur at C1-C3, if a child is getting a CT head to rule out TBI they will usually include slices down to C3 and pick up the vast majority of c-spine injuries.

Pediatric Chest Trauma

Children have compliant chests and thus sustain musculoskeletal thoracic injuries far less frequently (5% of traumas). However, due to this elasticity, the most common injury is a pulmonary contusion. Obvious chest injuries are a red flag for more serious trauma as they are indicate a huge force.

PEARLS

Deflating the stomach can help patient breathing and with chest tube insertion.

POCUS is highly sensitive for pneumothorax

Pigtail Catheters have been shown to be as effective as large bore chest tubes in children with traumatic pneumothorax .

PITFALLS

Don’t expect traditional adult injury findings: Absence of chest tenderness, crepitus and flail chests does not preclude injury.

CXR may miss early findings: Pulmonary contusions may only appear days later

Abdominal Pediatric Trauma

The vast majority of pediatric patients with abdominal trauma are treated conservatively with only 5% requiring surgery as most present with solid organ injuries. Any polytrauma patient with hemodynamic instability should be considered to have a serious abdominal injury until proven otherwise. The abdominal physical exam can be misleaded as 20-30% of pediatric trauma patients with a “normal” exam will have significant abdominal injuries on imaging.

Beware the mechanism: Seatbelt or handle bar signs as well as signs of abuse suggest serious injury.

Beware: 20-30% of pediatric trauma patients with a “normal” abdominal exam will have significant abdominal injuries on imaging.

Abdominal imaging in Pediatric Trauma

FAST is very specific but poor sensitivity for abdominal injuries in children

- FAST (+), pt stable -> CT

- FAST (+), pt unstable ->

- Decompensated shock -> direct to surgery

- Active bleeding necessitating ongoing blood transfusion -> surgery

- Resuscitation leading to stable hemodynamics – > CT

- FAST (-), high clinical suspicion of injury or elevated liver enzymes -> CT

- FAST (-), low clinical suspicion – > serial physical exams and FASTs

Indications for CT abdomen depend on whether the patient is considered high risk or low risk for significant injury

HIGH RISK – Indications for CT

- History that suggests severe intraabdominal injury

- Concerning physical – tenderness, peritoneal signs, seatbelt sign or other bruising

- AST >200 or ALT >125

- Decreasing Hb or Hct

- Gross hematuria

- Positive FAST

LOW RISK – Clearing the abdomen without CT (PECARN RULE – 99.9% NPV)

- No evidence of abdominal wall or thoracic wall trauma

- GCS>13

- No abdo pain or tenderness

- Normal breath sounds

- No history of vomiting

The value of the PECARN rule is for the patient that has a worrisome mechanism of injury yet fulfills the criteria of the rule, CT imaging is not required. Note that while the sensitivity of this rule is very high, the specificity is poor. Beware not to assume that a patient requires a CT if they have one or more of the criteria present.

Which pediatric trauma patients do not require a pelvic x-ray?

Based on a study out of The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto in 2015 a pelvic x-ray can be forgone if the following criteria are fulfilled:

- Hemodynamically stable

- Normal GCS

- No evidence of abdominal injury

- Normal pelvic exam

- No femur fractures

- No hematuria

Update 2018: A retrospective review of over 42,000 pediatric patients with blunt trauma showed no associated mortality benefit of whole body CT imaging compared to selective body CT imaging. Further, additional injuries identified on whole body CT were not life-threatening or did not change management. Abstract

Update 2021: Retrospective trauma registry review of 385 bicycle injuries in children, divided into handlebar (27.8%) and nonhandlebar injuries (72.2%). Handlebar injuries were more likely to cause abdominal solid organ injuries which required intervention, as well as cause soft tissue injuries (ex. thigh, abdominal wall, or genital lacerations). Abstract

Lab Monitoring and Prognosis in Pediatric Trauma

The B.I.G. Score: Prognosticating the pediatric trauma patient

Predicts mortality at scores below 16

BASE DEFICIT + (2.5 x INR) + (15 – GCS)

Serial Hb and Hct can be used along with serial physical exams and FASTs to assess for ongoing bleeding.

Tranexamic Acid (TXA)

While TXA use is not standard of care in pediatric polytrauma, our experts suggest it’s use in adolescent patients based on the CRASH-2 trial, and to consider its use within 3 hours of injury in younger patients who you anticipate will require blood transfusion. An observational military study in 2014 called PED-TRAX of 766 injured pediatric patients suggested that TXA was safe and was independently associated with decreased mortality. It also suggested improved discharged neurologic status and decreased ventilator dependence in the TXA group.

Transport of the pediatric trauma patient

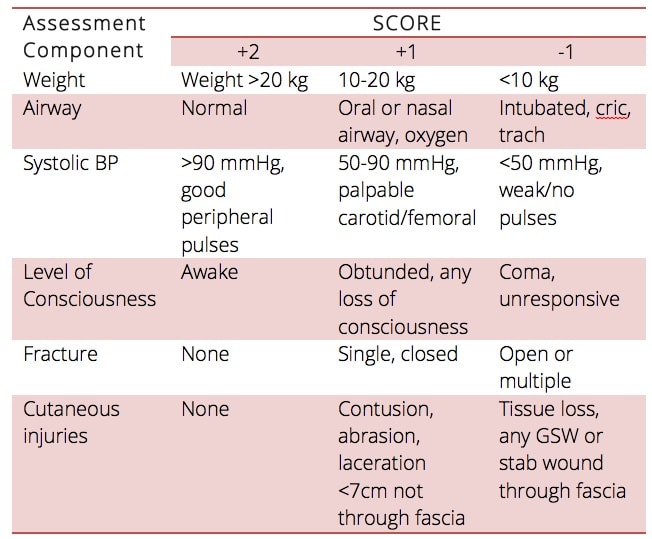

Pediatric Trauma Score: Indications for transport to a pediatric trauma center

The pediatric trauma score predicts mortality and need for transport. A score >8 imparts 0% mortality. Those with a score <8 should be transported to a trauma center. CT imaging should never delay transport to a trauma center.

Transport Checklist

- Identify, address and communicate life threatening injuries to trauma center

- Control airway, secure ETT, ensure sedation

- EtCO2 monitor to monitor ventilation strategy

- Secure tubes (OG, NG, Foley, chest tubes)

- Analgesia – fentanyl infusion

- Vascular access (IV or IO)

- Bind pelvis as indicated

- Splint fractures

- Antibiotics for open fractures

- TXA for hemorrhagic shock

- Blood products should be given as indicated, but massive transfusion protocols should be done at the receiving trauma center

- Paperwork (labs, imaging, notes)

For more on paediatric trauma on EM Cases:

Rapid Reviews Video on Pediatric Trauma

For more EM Cases content on Pediatric Emergencies check out our free interactive eBook,

EM Cases Digest Vol. 2 Pediatric Emergencies here.

Drs. Alnaji, Beno and Helman have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Jakob H, Lustenberger T, Schneidmüller D, Sander AL, Walcher F, Marzi I. Pediatric Polytrauma Management. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2010;36(4):325-38.

- Acker SN, Ross JT, Partrick DA, DeWitt P, Bensard DD. Injured children are resistant to the adverse effects of early high volume crystalloid resuscitation. J Pediatr Surg. 2014 Dec;49(12):1852-5.

- Advanced trauma life support (ATLS®): the ninth edition. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(5):1363-6.

- Jakob H, Lustenberger T, Schneidmüller D, Sander AL, Walcher F, Marzi I. Pediatric Polytrauma Management. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2010;36(4):325-38.

- Kenefake ME, Swarm M, Walthall J. Nuances in pediatric trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2013;31(3):627-52.

- Loiselle JM, Cone DC. Effect of out-of-hospital pediatric endotracheal intubation on survival and neurological outcome: a controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38(3):352-3.

- Kochanek, PM et al. Guidelines for the acute medical management of severe traumatic brain injury in infants, children and adolescents – 2nd edition. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 13(1), (2012).

- Mahajan P, Kuppermann N, Tunik M, et al. Comparison of Clinician Suspicion Versus a Clinical Prediction Rule in Identifying Children at Risk for Intra-abdominal Injuries After Blunt Torso Trauma. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(9):1034-41.

- Haasz M, Simone LA, Wales PW, et al. Which pediatric blunt trauma patients do not require pelvic imaging?. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(5):828-32.

- Marx J, Walls R, Hockberger R. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

- Pieretti-vanmarcke R, Velmahos GC, Nance ML, et al. Clinical clearance of the cervical spine in blunt trauma patients younger than 3 years: a multi-center study of the american association for the surgery of trauma. J Trauma. 2009;67(3):543-9.

- Dervan LA, King MA, Cuschieri J, Rivara FP, Weiss NS. Pediatric solid organ injury operative interventions and outcomes at Harborview Medical Center, before and after introduction of a solid organ injury pathway for pediatrics. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(2):215-20.

- Borgman MA, Maegele M, Wade CE, Blackbourne LH, Spinella PC. Pediatric trauma BIG score: predicting mortality in children after military and civilian trauma. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):e892-7.

- Davis AL, Wales PW, Malik T, Stephens D, Razik F, Schuh S. The BIG Score and Prediction of Mortality in Pediatric Blunt Trauma. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):593-8.e1.

- Zebrack, M, Dandoy, C, Hansen, K, Scaife, E, Mann, NC, Bratton, SL. Early resuscitation of children with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics, July; 124 (1); 56-64 (2009).

- Roberts I, Shakur H, Coats T, et al. The CRASH-2 trial: a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of the effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events and transfusion requirement in bleeding trauma patients. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17(10):1-79.

- Eckert MJ, Wertin TM, Tyner SD, Nelson DW, Izenberg S, Martin MJ. Tranexamic acid administration to pediatric trauma patients in a combat setting: the pediatric trauma and tranexamic acid study (PED-TRAX). J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(6):852-8.

Other FOAMed Resources on Pediatric Trauma

EMDocs peds trauma pearls and pitfalls

CanadiEM reviews TREKK mulitrauma recommendations

TREKK bottom line recommendations on severe head trauma

TREKK bottom line recommendations on multisystem trauma

EMCrit Severe Pediatric Trauma with Michael McGonigal

Pediatric EM Morsels on Low Risk for Intra Abdominal Trauma

PEM Playbook covers Multisystem Trauma in Children Part One: Airway, Chest Tubes, and Resuscitative Thoracotomy

For more learning on pediatric EM download EM Cases’ free eB00k “Pediatric Emergencies“

Now test your knowledge with a quiz.

What a great episode, thanks so much to you all. I had a couple of questions: firstly about the airway management in severe head injury. When you give 2-5mcg/kg fentanyl to blunt the ICP rise in response to intubation, I would expect this dose to render the patient apnoeic, which would in turn require careful bagging for the few minutes between giving the fentanyl and inserting the laryngoscgope. How great is the risk of inflating the stomach significantly enough by bagging (even if you try to bag very carefully) that it causes problems either by causing the patient to vomit or by impairing respiratory excursion? Is this enough of a worry to warrant putting an NGT / OGT down first to deflate the stomach and if so, what is the response in ICP to NGT insertion?

My second question relates to negative FAST in moderate risk blunt abdominal trauma. If you are in a centre that has the capability to observe a patient in whom you do not suspect an abdominal injury requiring operative intervention, but which has surgeons who can take the patient to theatre if there is deterioration, would you be more likely to observe with serial examination and , vital signs than do a CT, even if they have a small amount of tenderness (eg responds to analgesia, normal vital signs over time). Do you ever use a negative FAST (with its low sensitivity) to prioritise actions in the resus room when a patient has multiple injuries requiring fairly urgent fixing but not in theatre, eg limb trauma, eg you might decide to reduce a fracture dislocation prior to CT in a polytrauma once you know that their FAST is -ve (and providing they are stable-ish)?

And lastly, when you do need a CT, are you doing single phase IV contrast only with water for oral or no oral contrast?

Really appreciate your thoughts on these if you can spare the time.

Thanks again, such an interesting podcast.

Super episode..can’t thank enough..