The Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians’ Future of Emergency Medicine in Canada committee has established three goals to pursue as part of its overarching purpose to enhance timely access to high-quality emergency care: 1. to define and describe categories of emergency departments (EDs) in Canada; 2. to define the full-time equivalents (FTEs) required by category of ED in Canada; and 3. To recommend the ideal combination of training and certification for emergency physicians in Canada. [1]

Part 2a of this blog post (WTBS 26) explored what improved resilience would mean to the function of emergency medicine in the broader health care system and its implications for ED crowding and access block. Part 2b (WTBS 27) considers how a readiness/resilience approach might improve access to high-quality emergency care in a broad geographic region by reducing the shortage of emergency physicians in Canada and addressing the thorny question of how to optimize the number and distribution of EDs in a geographic region.

CoPs are typically understood as groups of people who interact regularly because they care about the same real-life problems or hot topics and on this basis negotiate a shared practice [2]

When you view the health care system through a resilience lens, the conversations and potential tensions in the domain of emergency medicine training and certification may change, or at least get reframed. For example, what has been considered by many a weakness in our system may actually make our system more resilient. [3] That is, having various pathways to certification—including the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada’s five-year program, the College of Family Physicians of Canada’s , practice-eligible routes, and pediatric emergency medicine fellowships—provides some optionality, diversity, and redundancy in the system.

In the cross-fertilization and epigenetics of this certification ecosystem, a strong (and resilient) network of emergency physicians and educators has emerged across Canada who support each other and to a large degree have adapted to fill local and regional niches and needs. Furthermore, when emergency medicine is seen as a pluralistic community of practice working toward a common good (the Quadruple Aim), then there is room for a both/and rather than an either/or approach to certification. [4]

That is, a resilient health care system supports the need for more emergency physicians with certification in emergency medicine (through several pathways) and supports ongoing maintenance of competence opportunities for comprehensively trained and experienced family doctors who are the foundation of rural emergency medicine care.

As we evolve to meet the emergency care needs of our population across a vast and variable geography, form should again follow function. [5] In some provinces of Canada, about 50 per cent of EDs are considered small, rural EDs, and though they may see just slightly more than 10 per cent of all ED visits in a province in a year, it is essential that health system redesign meets the needs of the entire population. We must integrate all perspectives, including the rural populations we serve. Without that, resilience in the broader system suffers. From an educational and maintenance of competence support perspective, that is where a resilient health system might also invest in a program such as the three-month Supplemental Emergency Medicine Experience in Ontario for the niche it fills. [6]

Another strategy in a resilient health care system would be to create and support hub-and-spoke regionally integrated networks of care. In this context, collegial, pluralistic communities of practice could emerge where there is some element of shared rostering, integrated scheduling (and mitigation strategies in the setting of ED closures caused by illness and/or quarantine), and educational opportunities such as shared virtual rounds/teaching and simulation sessions. An added layer of resilience to this would be a provincial-level locum program (such as Health Force Ontario) that can act as a smoothing pool of emergency physician assets in situations with imminent and unexpected ED closures.

Impact of network design on health human resource needs

Spatial health is the application of geographical thinking to epidemiology, population health, and health services design and delivery.

Before we can determine how many certified emergency physicians and comprehensive-practice rural family physicians we need in Canada, or in any given province, we first must clearly answer these questions:

- What is the purpose of an ED (see WTBS 26)?

- How do we optimize the number and distribution of EDs in a geographic region?

- How do we categorize EDs (i.e., what are the equipment, staffing certification, diagnostic imaging/lab/referral access, etc. standards at what level of ED—1, 2, 3, 4, say), and at what point on that standard spectrum should we no longer define a facility-based outpatient department or urgent care centre an ED?

- Where and how will virtual care supplement our systems? [9]

Currently, the standards, number, and distribution of EDs vary significantly between provinces and these have become politically controversial issues. [10,11] But avoiding these issues altogether contributes to the fragility of many systems.

In a resilient health care system paradigm, service delivery models could be balanced and supported in a way that improves access to high-quality emergency medicine in urban and rural areas through integrated networks of emergency care (see Figure 1). [43] We can’t determine how many emergency physician FTE positions we need without understanding how many ED hours must be covered (i.e., how many EDs do we need in a region, and how many hours of coverage per day should each have). [12]

Figure 1: Polarity management [4] schematic describing the tension between maximizing the consolidation of EDs versus maximally distributing EDs in a geographic region. In a resilient health care system there will be a tendency toward the both/and approach of balancing the upper two quadrants. In a fragile system the pendulum will swing between either/or conflicts in the two lower quadrants.

Mind the gap

“The mismatch between the number of graduates and available jobs is due in part to a lack of data on future population health needs, so planners don’t always know where the areas of greatest demand will be.” [13]

As we look to define the FTE gap in emergency physician supply in Canada, we also need to value system resilience. While this a complex issue itself, [14] there is evidence that the country needs more certified emergency physicians. [1]

Interestingly, during COVID-19, with the relative decrease in ED visits in the hardest-hit areas of Canada, coupled with the emergency physician ethos of being willing to step up to the plate and the reduction in vacation options, some urban teaching centres reported emergency medicine graduates having trouble finding full-time job offers (even as regional and community EDs across the country continued to struggle with full roster readiness). Whether this is just a short-term epiphenomenon or a maldistribution problem (e.g., interprovincial bureaucratic and cost obstacles preventing the easy flow of emergency physicians from one region to another makes our system less resilient) . This illustrates the need to corroborate billing/past utilization methodology and survey data with real-time, needs-based, behaviourally informed methodology and modelling. [12,13,14] Regardless, under the current provincial postgraduate medical education funding constraints and flawed provincial physician resource plans, a resilient health system might look for more innovative ideas.

One possibility would be for the federal government to consider directly funding more emergency medicine residency positions in all emergency medicine streams to fill the current (and projected) FTE gaps in this domain. This is justified because of its first resilience dividend—creating a cohort of certified emergency physicians who could act as “reserves” to be redeployed in the context of a major regional emergencies—and it would create a safety buffer in the setting of a national surge in emergency medicine care needs. At the same time, it has the second resilience dividend of leading to fully staffed EDs across the country during normal times, which minimizes ED closures, supports physician wellness, and reduces the costs of regions and provinces poaching emergency physicians from one another; in short, this would create a more ready and resilient system. Obviously, similar models could be used for registered nurse and/or paramedic training, especially where there are FTE gaps there.

As described in this archived document [15], the National Office of Health Emergency Response Teams (NOHERT) was created under the jurisdiction of the Public Health Agency of Canada. The goal of NOHERT was to “train and certify Health Emergency Response Teams across the country, and to ensure they are ready to be deployed on a 24-hour basis to assist provincial, territorial or other local authorities in providing emergency medical care during a major disaster.” As an example, NOHERT was integrated into the medical preparation for and response to the Olympic Games held in Vancouver, British Columbia. Ultimately, NOHERT was a casualty of early restructuring changes at the Public Health Agency of Canada, [16] which led to the calculated risk of not having that health human resource surge capacity for a pandemic; but this has made our systems less resilient. We could learn from what did (and didn’t) work with previous incarnations of NOHERT and create a new and improved version.

When you think of emergency physicians as the stem cells of the acute care health system, [17] if some emergency physicians were not needed specifically in an ED setting during a crisis (such as a pandemic or other large-scale disaster), they could, depending on their training, support ICU surges, primary care and assessment centre needs, and/or pediatric-related services.

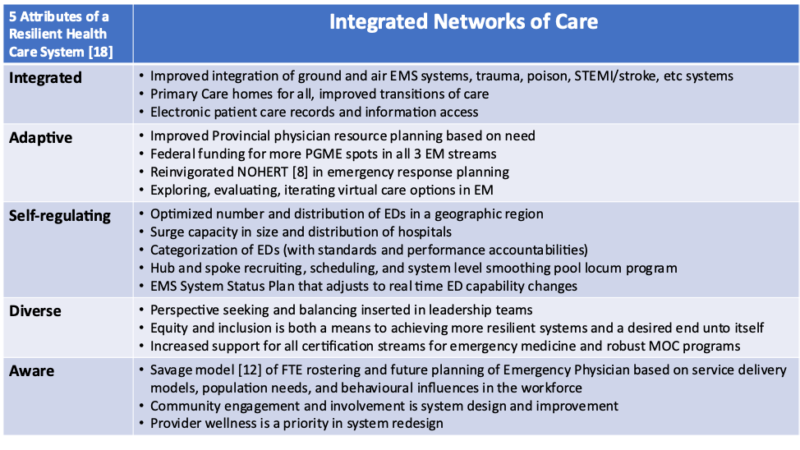

As shown in Figure 2, the five attributes of a resilient system

Figure 2. How the five attributes of a resilient health care system are reflected in integrated networks of care

Conclusion

“The COVID-19 pandemic has applied unprecedented pressure to health care systems around the globe and demanded dynamic adaptation of delivery and structure. In so doing, the pandemic has unmasked remarkable rigidity and, therefore, vulnerability in our systems.” [19]

—Dr Michael Gardam

Common patterns underlie the specific problems and the unique performance characteristics of each health care system [20]. As health care systems struggle with their responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, they must simultaneously resist the pull of returning to the old normal. An approach to health care system redesign should integrate readiness/resilience into the Quadruple Aim of health care and create the conditions for the emergence of better systems through simple rules or minimum specifications.

There is a developing consensus that building resilience is one way to address those common patterns in complex systems. As described in WTBS 26, it becomes apparent how this concept can improve our system-as-a-whole approach to patient access and flow. And, in so doing, resilient health systems will clarify and focus the function, roles, and responsibilities of emergency medicine as a keystone node in the broader networks of care (as other subsystems are enabled to focus on their mandates, roles, and responsibilities).

In this follow-up to WTBS 26, this argument has been extended to suggest that when you apply the same principles of a resilient system (integration, adaptation, self-regulation, diversity, and situational awareness) to stabilizing and innovating emergency medicine care networks, this could also have a broad reach and positive effect on improving outcomes for the populations we serve. Reframing service delivery redesign in a resilient systems context opens a wider spectrum of potential solutions and should seed some more creative and yet pragmatic approaches to closing the large FTE gap in emergency medicine.

As COVID-19 has demonstrated, we cannot afford not to.

—Dr. David Petrie

Dr. David Petrie is an emergency physician and trauma team leader at the QEII Health Sciences Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He is also a professor in Dalhousie University’s Department of Emergency Medicine. Dr. Petrie’s primary academic interests include the teaching and assessment of critical thinking in medical education and the application of complexity science to health system design.

References

- Sinclair D, Toth P, Chochinov A, Foote J, Johnson K, McEwen J, Messenger D, Morris J, Pageau P, Petrie D A, Snider C. “Health human resources for emergency medicine: a framework for the future” CJEM 2019; 22(1), 40-44 doi:10.1017/cem.2019.446

- Wenger E, McDermott R, Snyder WM. “Seven Principles for Cultivating Communities of Practice.” Research Gate 2014.

- “Principle one – Maintain diversity and redundancy”. GRAID at Stockholm Resilience Centre. https://applyingresilience.org

- Burns LR. “Polarity management: the key challenge for integrated health systems.” J Healthc Manag 1999; 44(1):14-31; discussion 31-3.

- Grumbach K. “Redesign of the Health Care Delivery System: A Bauhaus “Form Follows Function” Approach.” JAMA 2009; 302 (21): 2363-4 doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1772

- SEME Supplemental Emergency Medicine Experience. https://semedfcm.com.

- Martinez R and Carr B. “Creating Integrated Networks Of Emergency Care: From Vision To Value.” Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 32 (12):2082-90

- Dummer TJ. “Health geography: supporting public health policy and planning.” CMAJ. 2008; 178(9): 1177-1180 doi:10.1503/cmaj.071783

- Ho K. “Virtual care in the ED: a game changer for the future of our specialty?” CJEM 2021; 23, 1–2

- McEwen J, Borreman S, Caudle J, Chan T, Chochinov A, Christenson J, Currie T, Fuller B, Howlett M, Koczerginski J , Kuuskne M,. Lim R K, McLeod B, Pageau P, Paraskevopoulos C, Rosenblum R and Stiell I G. “Position Statement on Emergency Medicine Definitions from the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians”. Published online by Cambridge University Press: 2018

- Vanderhart T. “Rural areas deserve real emergency care, doctors say – and that could mean closing ERs”. CBC News. 2017, April 24.

- Savage D, Petrie DA. “Assessing the long-term emergency physician resource planning for Nova Scotia, Canada.” CJEM2019; 21(S1):S35-36

- Owens, B. “Unemployed physicians a sign of poor workforce planning.” CMAJ 2019; 191 (23)

- Jeon SH, Hurley J. “Physician resource planning in Canada: the need for a stronger behavioural foundation.” Can Public Policy 2010; 36(3):359-75. doi: 10.3138/cpp.36.3.359. PMID: 20939138.

- Audit Report Emergency Preparedness and Response. Audit Services Division Public Health Agency of Canada. June 2010. epr-miu-eng.pdf (canada.ca)

- Robertson G and Curry B. “Internal audit lays bare problems at Public Health Agency of Canada OTTAWA The Globe and Mail” PUBLISHED JANUARY 22, 2021

- Epstein D. “Range: Why Generalists Triumph In A Specialized World.” Book (Hardcover) www.chapters.indigo.ca

- Kruk M E, Ling E J, Bitton A, Cammett M, Cavanaugh K, Chopra M, el-Jardali F, Macauley R J, Muraguri M K, Konuma S, R, Martineau F, Myers M, Rasanathan K, Ruelas E, Soucat A, Sugihantono A and Warnken H. “Building resilient health systems: a proposal for a resilience index.” BMJ 2017; 357

- Kraus R. “Ecological resilience and crisis leadership in the COVID-19 pandemic In conversation with Dr. Michael Gardam”. Can J Physician Leadersh 2020; 7(1):38-42.30

- Braithwaite J. “Changing how we think about healthcare improvement.” BMJ 2018; 361 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2014

Leave A Comment