In WTBS 25 COVID-19 Pandemic Exposes the Importance of Resilience in Health System Redesign, Dr. David Petrie explored the evolving concept of a resilient health care system and how the pandemic exposed the urgent need to apply these concepts to our health care systems broadly. Now, in early March 2021, while we struggle to contain second waves and avoid third waves, we are also at a point where vaccine development and production allow us the luxury of dreaming and planning for a post-pandemic world, even if its arrival will be variable and many challenges remain.

The pandemic has exposed a number of problems in the health care system where I practise (Ontario, Canada), most of which are present to some degree broadly in high-income countries. These included a long-term care/elder care sector that was vulnerable to a pandemic, silos between sectors (especially between community and acute care and post-acute/long-term care), dependence on 20th century modes of care (including over-reliance on in-person appointments and fax machines), and decision-making structures at all levels that were the opposite of nimble.

To a variable extent, but remarkably so in many places, the need to respond to the pandemic’s challenges has driven innovation. This has included systems creating new structures to bridge gaps between silos (hospitals supporting long-term care homes, for instance), providers and patients adopting virtual care in a stunningly rapid fashion, and online communities of practice filling a void in the rapid dissemination of new knowledge.

In Ontario we are already discussing the best ways to hold on to and expand on the best pandemic-driven innovations as we emerge from the crisis. In part 2 of his post on system resilience, Dr. Petrie explores how the concepts apply to emergency departments and emergency care systems. Because these issues are so important, to do them justice we are posting these ideas in two parts: 2a (WTBS 26) looks at what it can mean for an emergency department (ED) that is situated in a resilient system, while 2b (WTBS 27) explores how we can address specific chronic challenges we face in emergency medicine in the context of resilience, including health human resources shortages and silos between smaller and larger centres in a region.

Thomas Friedman’s book The World Is Flat is an exploration of how globalization and modern communications technology have changed the world. Our emergency care systems entered the pandemic on decidedly bumpy terrain; can we use technology and innovation to flatten and protect them—to make them more resilient?

—Dr. Howard Ovens, March 2021

Emergency medicine function and flow in a resilient health care system

“What if there was a different starting point—the intended function of the health system—and planners worked backward to determine the form most suitable to that function?” [1]

—Dr. Kevin Grumbach, Chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco

The preface to the highly respected history of emergency medicine entitled Anyone, Anything, Anytime [2] asks many pointed questions: “… why were the sickest patients, who presented to the hospital’s community portal—the ‘ER’—attended to by the least-qualified physicians? Why did the field of emergency medicine develop outside the traditional house of medicine? Why did the most powerful medical fields, medicine and surgery, strongly oppose the development of emergency medicine as an academic discipline, even when it was obvious to everyone that emergency care … was substandard?” The answers to these and other questions lie in the social and political context of the times.

“Before COVID-19 Emergency” time could also be defined by some equally unsettling health system questions:

- Why, despite consistent and recurrent evidence of worsening patient outcomes, did hospitals accept that using the ED as a smoothing ward for admitted patients, while they wait for their in-patient beds, was a reasonable strategy? Or was it just the default settings of a system without accountabilities? [3]

- Why did the ED become the path of least resistance for patients trying to access primary care, continuing care from subspecialists, or postoperative/post-outpatient procedural care?

- Why, in a country with unemployed or underemployed medical and surgical subspecialists, is there evidence that we are 1,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs) shy of a full complement of emergency physicians to meet our current societal needs (which is set to rise to a 1,500 FTE gap by 2025 if there is no change to our HHR strategies)? [4]

- How do we optimize the number and distribution of EDs in a geographic region to improve access to and the quality of emergency care for our rural populations?

The answers to these questions partly lie in the implications of part 1 of this blog. If our systems are designed with an over-emphasis on efficiency, and if resilience is seen as an expensive luxury (rather than a necessary sustainability strategy over the long run), then our systems will evolve exactly as they have; as the saying goes, all systems are perfectly designed to achieve the results that they consistently achieve. Unfortunately, neglect, assumptions, and cognitive biases have contributed to dysfunctional system design in the past. [5,6,7]

In the future, resilient health systems would clarify and strengthen the intended roles and relationships of all sub-systems (including emergency medicine). In fact, that may be one of the surprising second-order impacts of working toward the Quadruple Aim and creating a resilient health system: Emergency medicine will fulfill the mandate it is meant to fulfill in the system, as will other components of the system.

The ethos of anyone, anything, anytime will remain the same; anyone, without regard to age, race, religion, gender, or socio-economic status, etc. (the caveat being that emergency care systems are designed for anyone with unexpected illness and injury, and the rest of the system would have the resilience to meet their own mandates); anything, from illness (physical and/or mental health) to injury; and anytime (24-7, 365 days a year).

Figure 1 describes the W5 of emergency medicine: the who, what, where, when and why . Hold this framing and language lightly; the intention is not that you agree with every word but more that there is a general, overarching consensus regarding the purpose and role of emergency medicine in health system redesign (at least for this thought experiment). If you currently work in an ED where the W5 of emergency medicine are being compromised by other roles and tasks, then you may be working in a fragile health system.

Figure 1. The W5 of Emergency Medicine

Flow follows form: access block through a readiness/resilience lens

“Emergency departments must not return to pre-covid days of overcrowding and lack of safety.” [9]

While form should follow function in resilient systems [1], access block follows from our current forms (i.e., the faulty structures and default processes) that have become concretized in a rigid health care system. There are many excellent resources describing what works and what doesn’t in hospital access and flow [10,11] but there isn’t one “must-do” list of fixes that work in all settings.[12] So, rather than describe what systems should do, the emphasis should be on how we do it and how we think about the problem in the first place.[12]

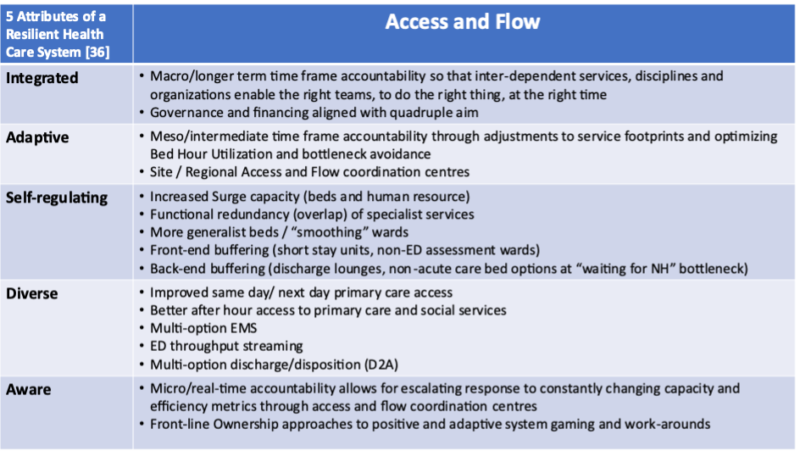

In that context, as described in part 1 of this blog, there are five attributes to a resilient health system: It is functionally integrated, adaptive, and self-regulating; it is aware of its current and future assets and risks; and it has diverse perspectives and options to meet population needs. [13]

First, a self-regulating system has surge capacity that allows it to be ready for increased demand in a crisis (dividend 1) while minimizing the disruption of essential services during inevitable cycles and normal surges (dividend 2). Among high-income countries, Canada has consistently had one of the lowest numbers of acute care hospital beds per 1,000 population, whereas South Korea, widely lauded for its pandemic readiness, has among the highest. [14] Along the same lines, limiting ED physician coverage hours [15] and/or RN/patient ratios and planning for the average (rather than the 75th percentile) day [16] also limits the surge capacity of systems (and adds to provider burnout and moral hazard, further making a health system less resilient).

Self-regulation also implies monitoring and maintaining efficient and effective bed-hour utilization—that is, what proportion of the 24-7 individual/ward/service bed hours are being used for what purposes. The dynamic relationship between wait times and utilization is mathematical , whether you are looking at hospital beds, ambulances, clinic appointment slots, or fast-food drive-throughs. With a bed-hour utilization approach, a resilient health care system can address bottlenecks in flow in real-time through the strategic use of buffers such as short-stay units and assessment bays; smoothing, non-ED “flex-zones” in inflow pathways; and discharge lounges and non-acute care bed locations in outflow. This is partly how the United Kingdom works toward meeting ED length-of-stay targets in the service of broader system goals. [17] It also plays a significant role in how Ireland improved ED wait times and quality of care despite higher volumes and severe financial constraints in a redesign of its general medical systems country-wide. [18]

An integrated system would learn from the common mistake of suboptimization in a system, where optimizing performance in a silo actually worsens overall system performance. [19] An example of this in the ED overcrowding context is the establishment of ambulance offload teams/zones in isolation. While patients may be offloaded more efficiently upon arrival at the ED, other key challenges such as bed wait times have not been addressed, leading to even more patients waiting in the ED . Suboptimization in parts of a system can lead to hitting one target but missing the bigger point.

In fact, narrowly focusing on any one target without systems-aware, self-correcting adaptations in service of the common good or the broader system’s goals (i.e., the Quadruple Aim) can lead to dysfunctional systems. As Goodhart’s law states, when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure [20]; or, targets for parts of systems are leaky in relation to whole-system goals; or, humans game systems to serve selfish or siloed goals, and therefore continuous monitoring and course correcting in service of broader system goals and integration are essential.

A system redesigned with the attributes of diversity and awareness also has a better knowledge of patient and community needs, more robust decision-making structures, and more optionality built into the patient care journey. Streaming, as an example of operational optionality, is another strategy for resilient health systems to avoid bottlenecks. For example, multi-option emergency medical services [21] would change the paradigm to one in which mobile health units can give advice, connect patients with primary care practitioners, or book visits with other care locations besides just EDs. Canada has one of the lowest rates of same-day or next-day access to primary care [22]—again, adding to the vulnerability of the system by limiting functional redundancies in the system.

Streaming by acuity and complexity in the throughput portion of a patient’s ED journey also increases flow (and resilience). [23] For ED patients who can’t safely be discharged, ‘most appropriate service’ algorithms are necessary for specialists to define their roles clearly to avoid unnecessary redundancy, while ensuring there are no responsibility gaps that could leave patients in limbo – and waiting in the ED. [5] Of course, not everybody needs to be admitted. Multi-option disposition pathways from the ED (discharge to assess, [24] , better access to outpatient clinics, and telemedicine follow-ups) can also be developed in a system that values integration and enables adaptation as a strategy to avoid ED bottlenecks in the first place.

Necessity in systems creates innovation; accountability adapts and applies it in service of the system’s goals

If you want to understand the deepest malfunctions of systems, pay attention to the rules, and to who has power over them. [25]

Accountability (to the common good) is the operational manifestation of a resilient system that is aware, adaptive, and self-regulating. Thus, a system can be more resilient through accountability at scale and over time. [26] In relation to ED crowding, this can be considered at three levels or time frames: macro/long term, meso/medium term, and micro/real time. Prospective and whole-of-system (macro/long-term) accountability must be present at the executive and system funding/policy levels to enable the right teams to do the right things at the right times. That is:

- Are admitted patients boarded in the ED for more than 12 hours (90 percent of the time) [27]?

- Is there same-day, next-day, and after-hours access to primary care?

- Are non-emergent postoperative/procedural concerns, and specialist continuing care directed to same-day/next-day clinics rather than to the ED?

- Are there non-ED options for adult protection patients who require complex social and cognitive capacity assessments?

Yes, an ED often can do all those things, but this would not be considered ideal bed-hour utilization in the ED (especially when many other subtly but seriously ill and injured patients are waiting to be seen in the wait rooms and hallways).

There is a difference between using the ED as a safety net (the necessary role of catching the rare but important events for which the rest of the system just can’t be 100 per cent ready for 100 per cent of the time) and knowingly designing the system with the ED as a common (daily) pressure-release valve for inadequacies in the rest of the system. In a resilient health care system redesign, failures in the system (i.e., the near-constant use of a pressure release valve) would lead to the enabling of improvements in capacity and/or efficiency to avoid similar events in the future.

Failure can be used as information in a learning organization or health ecosystem, but failure eventually becomes the normalization of deviance in a fragile health care system. In fact, formulating the problem as an ecosystem resilience issue (requiring adaptation, functional redundancy, and safe surge capacity through buffers, etc.) rather than an engineering resilience issue (requiring compliance, pressure release valves, and fraying safety nets) improves our approach. [28]

Accountability at the hospital and regional levels (meso/medium term) requires reviewing performance against goals and metrics (understanding their utility and their limitations), publicly reporting them [29] and analyzing the Boundary, Authority, Role, and Tasks (BART) of each service or subsystem (why do they exist, what is their purpose in the broader system, and are they fulfilling their mandate). [30] At the meso level we must also analyze, learn, and correct in an iterative fashion. From this perspective on the system, connections can be made, and coordination improved, between and among organizations and sub-services. Advocacy can be directed for macro/longer term–level accountability and enabling can be directed downward to support front-line, real-time decision-makers while constantly adjusting and adapting as a learning organization. A system that allows a component of a broader system to shift the burden of responsibility to parts of the system that have responsibility without authority will be a fragile system. [31] Whether this is done intentionally or through long-accepted defaults in the system, that is for this level of accountability to discover and address.

Awareness and self-regulation through day-to-day, hour-by-hour system adjustment/correction (micro/real-time) accountability are also necessary. This can be operationalized through a patient-flow coordination centre interacting with other levels of accountability. [32] While it is true that accountability at the whole-of-system level to meet capacity needs leads to less stress at the meso level to meet efficiency needs, it is also likely that inadequate capacity and/or efficiency at either of those levels will lead to the need for tough real-time decision-making at the front-line level, where trade-offs and, frankly, rationing will have to occur. Some of this function can be handled through automatic most-appropriate-service rules or prehospital smoothing–type algorithms, [33] but often policies, bylaws, and procedures are no match for human behaviour, gaming, and stress-related work-arounds (especially in hospitals with siloed decision-making and challenged organizational cultures).

Real-time monitoring and iterative correcting are also necessary to minimize the emergence of the Jevons paradox [34] (where increased efficiency may lead to increased utilization; e.g., improved pathways for the care of the elderly in the ED lead to more GPs and/or social services sending frail and failing, but not acutely ill, elderly patients to the ED) and/or the Sam Campbell paradox [35] (where increased capacity leads to decreased efficiencies; e.g., more general medicine beds can lead to less compliance around early discharge planning and unjustifiably longer hospital lengths of stay).

In Figure 2 we can see how the five attributes of a resilient system are loosely aligned (but only loosely, as all of these strategies are interdependent) with strategies in a health care system that could improve access and flow in the ED.

Figure 2. How the five attributes of a resilient health care system are reflected in patient access and flow

Conclusion

The impact of these resilient health system strategies on ED crowding are not just theoretical. A recent study determined there are four common features of high-performing hospitals/systems in the realm of improved access and flow for patients: 1. senior executive involvement; 2. hospital-wide strategies; 3. data-driven management; and 4. performance accountability. [12] These are all manifestations of a health care system that adds readiness/resilience to its overarching Triple Aim.

Senior executive involvement can become the archetypal nurturing force that enables and catalyzes diverse, adaptive, and innovative service delivery models. Awareness and integration come through hospital-/system-wide strategies. Data-driven management also contributes to system awareness and real-time, as well as long-term/big-picture, self-regulation. A commitment to performance accountability is the archetypal, focusing force that adapts and applies system improvements in service of the common good (i.e., the Quadruple Aim).

Obliquely, but just as importantly, what may emerge from this approach is an emergency medicine system that is less encumbered and more empowered to fulfill its tripartite mission: 1. resuscitating and stabilizing the acutely ill and injured; 2. diagnosing and treating unscheduled health events; and 3. leading and coordinating emergency care across space and time. Part 2b of this blog (WTBS 27) will explore what a readiness/resilience aim would do to improve the third part of this mandate.

—Dr. David Petrie

Dr. David Petrie is an emergency physician and trauma team leader at the QEII Health Sciences Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He is also a professor in Dalhousie University’s Department of Emergency Medicine. Dr. Petrie’s primary academic interests include the teaching and assessment of critical thinking in medical education and the application of complexity science to health system design.

References

- Grumbach K. “Redesign of the Health Care Delivery System: A Bauhaus “Form Follows Function” Approach.” JAMA 2009; 302 (21): 2363-4 doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1772

- Zinck B. “Anyone, Anything, Anytime – History of Emergency Medicine” ACEP’s 50th Anniversary (2nd Edition) 2021 https://www.acep.org/

- Innes G. “Sorry we’re Full! Access block and accountability failure in the health care system.” CJEM. 2014; 16(0): 30-47

- Sinclair D, Toth P, Chochinov A, Foote J, Johnson K, McEwen J, Messenger D, Morris J, Pageau P, Petrie D A, Snider C. “Health human resources for emergency medicine: a framework for the future” CJEM 2019; 22(1), 40-44 doi:10.1017/cem.2019.446

- Srivastava R. “The patient who is no one’s problem is society’s nightmare.” The Guardian View 2019

- Campbell S G. “It is the system that is “failing to cope,” not the emergency department” CMAJ. April 08, 2019 191 (14)

- Campbell S G, Croskerry P, Petrie D A, “Cognitive bias in health leaders” 2017 PubMed https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470417716949 SAGE Journals

- Systems Innovation Course. 2020, April 12. www.systemsinnovation.io/post/systems-innovation-course.

- O’Dowd A. “Emergency departments must not return to pre-covid days of overcrowding and lack of safety, says college.” BMJ 2020; 369:m1848

- Rutherford PA, Anderson A, Kotagal UR, Luther K, Provost LP, Ryckman FC, Taylor J. “Achieving Hospital-wide Patient Flow.” IHI White Paper Institute for Healthcare Improvement 2020. www.ihi.org

- Javidan AP, Hansen K, Higginson I, Jones P, Petrie D, Bonning J, Judkins S, Revue E, Lewis D, Holroyd BR, Mazurik L, Graham C, Carter A, Lee S, Cohen-Olivella E, Ho P, Maharjan R, Bertuzzi B, Akoglu H, Ducharme J, Castren M, Boyle A, Ovens H, Fang C, Kalanzi J, Schuur J, Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Hassan T, Bodiwala G, Convocar P, Henderson K, Lang E. “Report from the Emergency Department Crowding and Access Block Task Force” IFEM 2020; https://www.ifem.cc/resource-library/

- Chang, A M, Cohen D J, Lin A, Augustine J, Handel D A, Howell E, Kim H, Pines J M, Schuur JD, McConnell K J, Sun B C. “Hospital Strategies for Reducing Emergency Department Crowding: A Mixed-Methods Study.” Annals of emergency medicine 2018; 71(4), 497-505.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.07.022

- Ovens H. “COVID-19 Pandemic Exposes the Importance of Resilience in Health System Redesign” EM Cases Waiting to Be Seen blog (emergencymedicinecases.com)

- Hospital beds per 1,000 people, 2018. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/hospital-beds-per-1000-people.

- Petrie D A, Campbell S G, Ross J A. “Predicting community emergency medicine needs and emergency physician compensation modeling; two sides of the same coin?” CJEM. 2012 Nov; 14 (6): 329

- Petrie D A. “WTBS 5 Emergency Physician Speed Part 2 – Solutions to Physician Productivity.” Emergency Medicine Cases Blog; 2016

- The Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Emergency Medicine Briefing: Making the Case for the Four-Hour Standard. https://www.rcem.ac.uk/docs/Policy/Making%20the%20Case%20for%20the%20Four%20Hour%20Standard.pdf. 2018.

- O’Reilly O, Cianci F, Casey A, Croke E, Conroy C, Keown A M, Leane G, Kearns B, O’Neill S, Courtney G. “National Acute Medicine Programme–improving the care of all medical patients in Ireland” Journal of Hospital Medicine 2015: Vol 10; 12

- PRINCIPLE OF SUBOPTIMIZATION PRINCIPIA CYBERNETICA WEBhttp://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/DEFAULT.html

- Koehrsen W. “Unintended Consequences and Goodhart’s Law”. Towards Data Science. 2018, Feb. 24.

- Choi B Y, Blumberg C, Williams K. “Mobile Integrated Health Care and Community Paramedicine: An Emerging Emergency Medical Services Concept.” Ann Emerg Med 2016; 67 (3): 361-6

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. “How Canada Compares: Results From The Commonwealth Fund’s 2016 International Health Policy Survey of Adults in 11 Countries — Accessible Report”. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2017.

- Saghafian S, Hopp W J, Van Oyen M P, Desmond J S, Kronick S L. “Complexity-Augmented Triage: A Tool for Improving Patient Safety and Operational Efficiency.” Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 2014:16(3):329-345

- “Quick Guide: Discharge to Assess”. NHS England. 2016 September 26. www.nhs.uk

- Meadows DH. Leverage Points: Places to intervene in a System”. The Sustainability Institute 1999

- Atkinson P, Innes G. “Patient care accountability frameworks: the key to success for our healthcare system.” Can J Emerg Med 2021

- Affleck A, Parks P, Drummond A, Rowe BH, Ovens H. “Emergency Department overcrowding and access block.” Can J Emerg Med 2013; 15 (6)359-370 https://doi.org/10.1017/S1481803500002451

- Kraus R. “Ecological resilience and crisis leadership in the COVID-19 pandemic In conversation with Dr. Michael Gardam”. Can J Physician Leadersh 2020; 7(1):38-42.30

- Lauren Vogel. “How can Canada improve worsening wait times?” CMAJ 2020; 192 (37) E1079-E1080; https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1095895

- Gabriel Green Z. “Boundary, Authority, Role and Task.” Research Gate 2015

- Kim D. “Shifting the Burden: Moving Beyond a Reactive Orientation”. https://thesystemsthinker.com

- Bournelis L. Taming a Wicked Issue: Building a Generative Team to Improve Access and Flow During a Pandemic.” 2020

- McLeod B, Zaver F, Avery C, Martin DP, Wang D, Jessen K, Lang ES. “Matching Capacity to Demand: A Regional Dashboard Reduces Ambulance Avoidance and Improves Accessibility of Receiving Hospitals.” Acad Emerg Med; 2010 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00928.x

- Jevons paradox. 2020, November 6. In Wikipedia. Retrieved 2021, February 4, from Jevons paradox – Simple English Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- Petrie D A, Comber, S. “Emergency Department access and flow: Complex systems need complex approaches.” Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 2020; 26 (1)

- Kruk M E, Ling E J, Bitton A, Cammett M, Cavanaugh K, Chopra M, el-Jardali F, Macauley R J, Muraguri M K, Konuma S, R, Martineau F, Myers M, Rasanathan K, Ruelas E, Soucat A, Sugihantono A and Warnken H. “Building resilient health systems: a proposal for a resilience index.” BMJ 2017; 357

Leave A Comment