Dr. Sanjay Mehta & Dr. Jonathan Pirie, two experienced Pediatric EM docs from The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto discuss their approach to a variety of common, occult, challenging and easy to miss pediatric orthopedics diagnoses including: differentiating Septic Arthritis from Transient Synovitis of the hip, Toddler’s Fracture, Tillaux Fracture, Suprachondylar Fracture, ACL tear, tibial spine & Segond fractures. They also debate the value of the Ottawa Knee Rules in kids, non-accidental trauma, pediatric orthopedic pain management, the evidence for the best management of Buckle, Greenstick, Salter 1 and 2 distal radius fractures and lateral malleolus fractures.

Written Summary and blog post by Claire Heslop, edited by Anton Helman August 2013

Cite this podcast as: Mehta, S, Pirie, J, Helman, A. Pediatric Orthopedics Pearls and Pitfalls. Emergency Medicine Cases. August, 2013. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/episdode-35-pediatric-orthopedics/. Accessed [date].

Go to Episode 31 to hear Dr. Jordan Chenkin talk about ultrasound guided fracture reduction – his rant convinced me to start using POCUS to reduce fractures in the ED!

Check out fracture section on the trekk website – translating emergency knowledge for kids – for clinical practice guidelines on numerous pediatric fractures.

PEDIATRIC ORTHOPEDICS KNEE INJURIES

In general, children’s ligaments are stronger than their bones, thus fractures are more likely than sprains.

- Have a low threshold for imaging if suspicious.

- The same ACL-injury mechanism (sudden deceleration of distal leg with forward and rotatory movement) will cause a tibial spine fracture in a younger child, and an ACL tear in a teenager or adult.

Lachman test (check out this video demonstrating this test) for ACL tear involves pulling the proximal tibia anteriorly while holding the knee in flexion. It has good sensitivity(>80% and specificity of 95%) [Scholten RJ et al. J Fam Pract 2003;52:689]. The pivot shift test (valgus force and internal rotation to extended leg, which is then flexed to feel subluxation) is also sensitive for ACL tear. Always do a straight leg raise to rule out extensor mechanism rupture.

Check the X-ray for a Segond fracture, a vertically oriented avulsion fracture off the lateral proximal tibia. This is highly associated with ACL and meniscal tears.

Check out this video demonstrating the Lachman Test, Pivot Shift, and Drawer Test

Management of ACL Tears

- Short term immobilization (splint as needed, +/-crutches), but atrophy of quadriceps occurs quickly, so start range of motion in 2–3 days. Some experts recommend weight bearing as tolerated immediately.

- Surgical repair is delayed until range of motion has recovered. Refer to outpatient orthopedics.

Additional X-Ray Views

- Patellar fractures may only be seen on a “skyline view” (views patella with knee in flexion)

- Tibial spine and tibial plateau fractures are best seen on a “tunnel view”

Patella Subluxation & Fracture

- The child may feel a “pop”, from the kneecap subluxing, and feel unstable on the leg.

- First time patella dislocations and non-displaced fractures do need knee immobilization, with weight bearing as tolerated.

- Displaced fractures or fractures with an impaired extensor mechanism (unable to perform straight leg raise) need urgent orthopedic consultation.

- Remember kids with knee pain can be having pain from a source in the hip, so always examine the hip as well.

Do the Ottawa Knee Rules Apply to pediatric orthopedics patients?

Ottawa Knee Rules state that a standard knee series is indicated if:

- Age >55 years (this won’t apply to kids…) or

- Isolated tenderness of patella or

- Tenderness at head of fibula or

- Inability to flex knee to 90° or

- Inability to bear weight immediately after injury AND in the ED for 4 steps (limping is accepted)

Multicenter studies show these rules are 100% sensitive in children for clinically significant fractures and capable of reducing radiographs by 31% [Bulloch B et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:48].

Non-accidental Trauma

Some fractures always raise suspicion of non-accidental trauma (i.e. posterior rib fractures).

However non-accidental trauma can result in any type of fracture pattern. Always remember to be systematic when taking histories, and document carefully!

Clues for non-accidental trauma [Horsley L. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:1461]:

- Delay in presentation,

- Vague or inconsistent explanation of mechanism,

- Mechanism described that is inconsistent with injury,

- Injury inconsistent with developmental stage of child.

APPROACH TO THE CHILD WITH A LIMP

- Rule out septic arthritis

- Look for fractures, which can be very subtle, and ask about trauma

- Look for clues of systemic illnesses such as a rash, fever, bruising

- Consider age-specific diagnoses as appropriate

Assess the persistence of the limp from the history and observations of the child. Give analgesia, which can help improve the physical exam.

Use distraction and observation of the child at play to complete a full physical examination.

Differentiating Septic Arthritis from Transient Sinovitis

Transient synovitis of the hip is a self limited inflammation of the synovial lining. It is often preceded by a viral infection, and should resolve in 3–10 days. However, concurrent illness can make diagnosis challenging.

Pay attention to vital signs, general appearance (well or unwell appearing) and symptom progression.

The Kocher criteria for predicting septic arthritis gives increasing probability for each of the following criteria met [Kocher et al. J Bone Joint Surg-Am] 2004:86;1629.

- Non-weight-bearing on affect side

- ESR > 40 mm/hr

- Fever

- WBC >12,000

The Kocher rule is helpful to rule-in higher pre-test probability patients. Fever is probably the best criteria.

What about CRP? Lack of fever and a normal CRP make septic arthritis extremely unlikely

Ultrasound? Presence of an effusion can support a diagnosis, but cannot rule out septic arthritis.

Treatment: in patients you suspect septic arthritis, usually you can wait to start empiric IV antibiotics until after the joint can be aspirated. However, if there will be a significant delay, start antibiotics first.

Legg-Calve-Perthes

- LCP is avascular necrosis of femoral head, typically in a child aged 4–10.

- It can present insidiously, or may follow a hip injury.

- The initial x-ray can be normal, or show a very subtle change in appearance of the femoral head.

- Speak to radiology to carefully review the images, as findings may be subtle, and follow with a bone scan or MRI if high suspicion remains

Toddler’s Fracture is often occult

A commonly missed occult fracture is the Toddler’s fracture (spiral fracture in children 9 months to 3 years, usually of distal tibia – see page 4 for an example). It can present with subtle findings. Pain with ankle dorsiflxion or calf rotation should raise suspicion. Oblique views can help reveal the fracture.

Update 2018: A controlled ankle motion boot or a short leg back slab are preferred because they are associated with fewer complications and can be removed by the family or the family physician. For most children, no orthopedic follow-up is needed.

Avulsion fractures and bowing aka greenstick fractures, are also frequently missed on plain X-ray.

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphyses (SCFE)

SCFE is easy to miss! This can present subtly, with pain that radiates into the thigh or knee. Typical patients are older children, overweight, but also skeletally immature.

On exam, pain is usually greatest with internal rotation of the hip, and they can present with the hip held in external rotation.

Get x-rays of both hips, including frog’s-leg view in addition to standard views. Look for Kline’s line, the line from the external part of femoral neck, which should intersect part of the femoral head.

As it slips, the femoral head becomes medial to that line. Compare both sides, but remember SCFE can be bilateral.

If suspicious, call orthopedics—these cases need surgical management and SCFE will worsen if patients continue to weight bear.

Tips for fracture pain management

- Use age-appropriate pain scores.

- Start with ibuprofen/acetominophen (there is some evidence that ibuprohen lowers pain scores significantly better than acetominophen)

- Add oral narcotics, or IV if planning a reduction. Consider intranasal fentanyl, or intranasal ketamine.

- Morphine (0.2 mg/kg up to 5mg per dose, with instructions about side effects) may be used in addition to ibuprofen/acetominophen for severe pain after discharge.

Codeine is not recommended, due to variations in its metabolism, and adverse side effects.

PEDIATRIC ANKLE FRACTURES

Salter Harris (SH) fractures around the growth plate (mnemonic SALTR):

I – S = Slip. Fracture of the cartilage of the physis (growth plate)

II – A = Above. Fracture above physis.

III – L = Lower. Fracture below the physis in the epiphysis.

IV – T = Through. Fracture is through the metaphysis, physis, and epiphysis.

V – R = Rammed. The physis has been crushed/heavily damaged.

Ottawa Ankle Rules is highly sensitivity for ankle fractures [Boutis K et al. Lancet.2001;358:2118], except SH-1. MRI evidence suggests SH-1 fractures are similar to a sprain, and do well when treated as such [Boutis K et al. Injury. 2010;41:852].

Non-displaced SH-II lateral malleolar fractures heal as well in an ankle stirrup brace as in a cast or boot, but patients prefer an ankle brace, and mobilize earlier. [Boutis K et al. CMAJ 2010;182:1507].

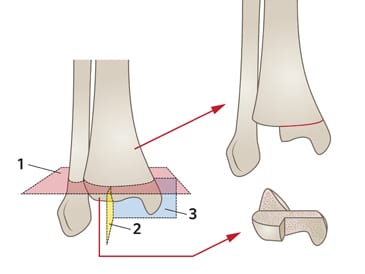

Tillaux & Triplanar Fractures

Tillaux fracture is an intra-articular SH-3 with avulsion of the anterolateral tibial epiphysis.

- Often from a low energy mechanism, in children with partial growth plate fusion (age 11–15).

Look carefully for a triplanar fracture in these children (an unstable combo of SH-1, SH-2 and SH-3), which requires operative management.

PEDIATRIC WRIST FRACTURES

Buckle fractures of the distal radius heal well in a splint, with greater patient preference over a cast [West S et al. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:325].

Studies indicate home splint removal, once symptoms resolve, may be safe and preferred to a clinic visit [Plint et al. Pediatrics. 2006;117:691].

Greenstick fractures (one cortex broken, the other intact) that are minimally angulated also do well with minimal splinting. Minimally angulated transverse fractures can also be treated similarly [Al Ansari K et al. CJEM 2007;9:9].

SUPRACONDYLAR FRACTURE

Examine the entire limb, up to the clavicle, and examine the joint above and below the painful site for a second fracture.

Supracondylar fractures are the most common elbow fractures.

Suprachondylar fractures have a high risk of neurologic and vascular injuries.

Brachial Artery injury is reported in up to 20% of displaced fractures with 80% of these regaining pulses after closed reduction.

Clinical Pearl: If pulseless, the child will usually be holding their arm in extension. Try flexing at the elbow 15-20 degrees and splint while waiting for emergency reduction.

The anterior interosseous nerve injury is the most common nerve injury in extension-type injuries, while ulnar neuropathy is the most common in flexion-type injuries.

To test motor function of the anterior interosseus nerve, look for weakness in flexors of IP joint of thumb and DIP joints of index and middle fingers by observing how the patient pinches using their thumb and index finger. Normally when an individual pinches something between their index finger & thumb, the MP & IP joints of thumb and index finger are flexed; with nerve damage, the distal phalanges of thumb and index finger are extended or hyperextended.

Upper extremity peripheral nerve testing

Ask the child to do hand signals to test motor function of each nerve.

- Radial nerve – make a “thumbs up”

- Median nerve – make a fist, and pinch a piece of paper with a pincer grip

- Ulna nerve – make scissors with the index and middle finger, or a ‘peace’ sign

For the sensory examination, test the first dorsal webspace (radial), dorsum of 2nd or 3rd fingertip (median) and fifth fingertip (ulna).

Pitfall: Avoid multiple attempts at closed reduction given the vulnerable position of the neurovascular structures

Pitfall: Flexing the elbow to 90 degrees when immobilizing a patient with a suprachondylar fracture who has significant swelling may increase the risk of compartment syndrome, as this will decrease blood flow.

Approach to the pediatric elbow X-ray

For images of each of these steps visit Don’t Forget the Bubbles blog

- ‘Figure of Eight sign’ – confirms a true lateral

- Anterior fat pad – ‘Sail sign’ – an enlarged sail shaped hypodensity should raise suspicion for a fracture

- Posterior fat pad – any hypodensity posterior to the humerus should raise suspicion for a fracture

- Radio-capitellar line – a line through the middle of the radius normally bisects the capitellum; any disruption of this line should raise suspicion for a fracture

- Anterior humeral line – a line along the anterior border of the humerus should bisect the middle 1/3rd of the capitellum; any disruption should raise suspicion for a fracture

- ‘CRITOE’ – Capitellum, Radial Head, Internal epicondyle, Trochlea, Olecranon, External epicondyle

Review each ossification center, which appear approx. every 2 years from age 2–3, to rule out an avulsion fracture masquerading as an ossification center.

CRITOE mnemonic for elbow growth plates

C- capitellum

R- radial head

I – inner (medial) epicondyle

O – olecranon

E – external (lateral) epicondyle

Pearl: consider x-ray of opposite elbow for comparison

For a video tutorial on suprachondylar fractures visit Radiopedia.

Pitfall: Do NOT apply a circumferential cast for suprachondylar fractures as it increases the risk for neurovascular damage and compartment syndrome

Pitfall: Flexing the elbow to 90 degrees when immobilizing a patient with a suprachondylar fracture who has significant swelling may increase the risk of compartment syndrome, as this will decrease blood flow.

Neurologic Exam for Supracondylar Fractures

These fractures have a high risk of neurologic and vascular injuries.

Ask child to do hand signals to test motor function of each nerve.

- Radial nerve – make a “thumbs up”

- Median nerve – make a fist, and pinch a piece of paper with a pincer grip

- Ulna nerve – make scissors with the index and middle finger, or a peace sign

For the sensory examination, test the first dorsal webspace (radial), dorsum of 2nd or 3rd fingertip (median) and fifth fingertip (ulna).

Consider Compartment Syndrome in kids displaying severe pain with suprachondylar fractures.

Immobilizing supracondylar fractures

Immobilize in a noncircumferential sugar-tong and gutter splint, to ensure stabilization of the distal humerus, with space to swell (to minimize compartment syndrome risk).

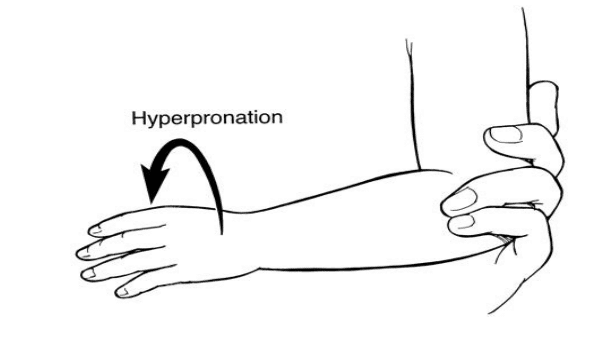

Pulled Elbow – ‘Nursemaid’ Elbow

If mechanism or history is unclear, then consider an X-ray. For a clear “pulled” elbow, the hyperpronation method is very (~95% effective) and may be more comfortable than the flexion/supination method [Bek D et al. Eur J Emerg Med].

Dr. Helman, Dr. Pirie and Dr. Mehta have no conflicts of interest to declare.

For more on Paediatric Emergencies download our free interactice eBook EM Cases Digest Vol. 2 Pediatric Emergencies

References

Boutis K, Constantine E, Schuh S, et al. Pediatric emergency physician opinions on ankle radiograph clinical decision rules. Acad Emerg Med 2010; 17:709. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20653584

Boutis, Kathy, et al. “Cast versus splint in children with minimally angulated fractures of the distal radius: a randomized controlled trial.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 182.14 (2010): 1507-1512. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2950182/

Boutis, Kathy, et al. “Sensitivity of a clinical examination to predict need for radiography in children with ankle injuries: a prospective study.” The Lancet 358.9299 (2001): 2118-2121. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11784626

Luhmann, Scott J., et al. “Differentiation between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children with clinical prediction algorithms.” The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 86.5 (2004): 956-962. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15118038

B. Bulloch, G. Neto, A. Plint, et al.: Validation of the Ottawa knee rule in children: a multicenter study. Ann. Emerg. Med.. 42:48-52 2003. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12827123

Scholten et al., 2003. Scholten R.J., Opstelten W., van der Plas C.G., et al: Accuracy of physical diagnostic tests for assessing ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament: A meta-analysis. J. Fam. Pract 2003; 52:689-694. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12967539

Horsley L. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:1461.

D. Bek, C. Yildiz, O. Kase, et al.: Pronation versus supination maneuvers for the reduction of ‘pulled elbow’: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Emerg Med. 16(3):135-138 2009 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19262394

Kocher, Mininder S., et al. “Validation of a clinical prediction rule for the differentiation between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children.” The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 86.8 (2004): 1629-1635. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15292409

D. Bek, C. Yildiz, O. Kase, et al.: Pronation versus supination maneuvers for the reduction of ‘pulled elbow’: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Emerg Med. 16(3):135-138 2009 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19262394

Al-Ansari, Khalid, et al. “Minimally angulated pediatric wrist fractures: Is immobilization without manipulation enough?.” CJEM 9.1 (2007): 9-15. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17391594

Plint AC, et al: A randomized, controlled trial of removable splinting versus casting for wrist buckle fractures in children. Pediatrics 2006; 117:691. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16510648

West, Simon, et al. “Buckle fractures of the distal radius are safely treated in a soft bandage: a randomized prospective trial of bandage versus plaster cast.” Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 25.3 (2005): 322-325. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15832147

For more EM Cases content on Pediatric Emergencies check out our free interactive eBook,

EM Cases Digest Vol. 2 Pediatric Emergencies here.

For more Pediatric EM learning visit trekk.ca – Translating Emergency Knowledge for Kids (TREKK) is a growing network of researchers, clinicians, health consumers and national organizations who want to accelerate the speed at which the latest knowledge in children’s emergency care is put into practice in general EDs – rural, remote or urban.

Now test your knowledge with a quiz.

Great summary, learnt lots, thanks