COVID-19 pandemic lessons offer pointers for redesigning a better health care system

As 2021 begins and vaccine approvals and rollouts gain speed, we are still in the midst of a challenging wave of illness and death in this pandemic. Yet it is not too early to talk about lessons learned; in fact, it is crucial we do so while we are all focused on this one subject.

In this guest post—part 1 of 2—Dr. David Petrie will talk about the need for our health care systems to be ready for challenges such as pandemics and how resilience in our systems will support our response. Dr. Petrie is the Senior Medical Director of the Provincial Emergency Program of Care in the Nova Scotia Health Authority in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In many ways this column builds on some of the concepts Dr. Petrie explained in WTBS 4 – Physician Speed: How Fast is Fast Enough and WTBS 5 – Emergency Physician Speed: Productivity Solutions and their impact on emergency department (ED) crowding. In part 1 he focuses on health systems while in part 2 he will more specifically address EDs and how their roles and relationships can be strengthened in the new normal.

Emergency service leaders have important voices for speaking on disaster preparation and response in our hospitals, health care systems, and communities. They also have a responsibility to bring their experience and perspectives to the recovery phase and to the redesign of health systems. Having a framework to inform our thinking will ensure our voices are aligned and have the greatest positive impact possible.

—Dr. Howard Ovens, January 2021

The case for readiness/resilience in post-COVID-19 health care systems

“A lasting implication of the pandemic is that resilient and efficient health-care systems will become part of the competitive advantage of nations.”[1]

— Kevin Lynch, vice-chair, BMO Financial Group, and former Clerk of the Privy Council; and Paul Deegan, CEO, Deegan Public Strategies and former deputy executive director, National Economic Council, the White House

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the fragility of human-made systems.[2] Overwhelmed and collapsing health care systems are scary. Necessary but reactive COVID-19 spending by health authorities has been costly. Fiscal stimulus packages in Canada have been more expensive still. The toll on human lives, relationships, mental health, and socio-economic stability has been huge and tragic. Recommendations from before the pandemic, and analysis since, suggest it did not have to be this way.

As we reflect on our COVID-19 response so far and how we gird our operations for the next (and future) waves of the pandemic, we must also catch up with the backlog of health care that was deferred or cancelled and the resulting human suffering. Have we learned any lessons? Can we create the conditions for our systems to evolve into safer, more resilient, and more sustainable systems in the long run?

Yes, the vaccines are arriving, but so, too, are the viral variants, and who knows when the next large-scale health system stressor will arrive. We do not have a choice. We must address health care system fragility in the new normal. Enhancing systemic resilience may require some investment, but ignoring it will cost even more over time.

What is readiness? What is resilience?

The definitions and proposed models of resilient health care are still crystalizing and evolving, but there is an emerging consensus on the overarching concept.[3]

Health care resilience has been defined as “the capacity of health actors, institutions, and populations to prepare for and effectively respond to crises; maintain core functions when a crisis hits; and, informed by lessons learned during the crisis, reorganise if conditions require it.”[4]

Figure 1 describes the five attributes of a resilient health system that rest on the important foundation of national leadership and policy, public health and health system infrastructure, a committed and adequately sized workforce, and global coordination and support.[5]

Figure 1 with permission BMJ license number 4985890371537, Jan, 2021

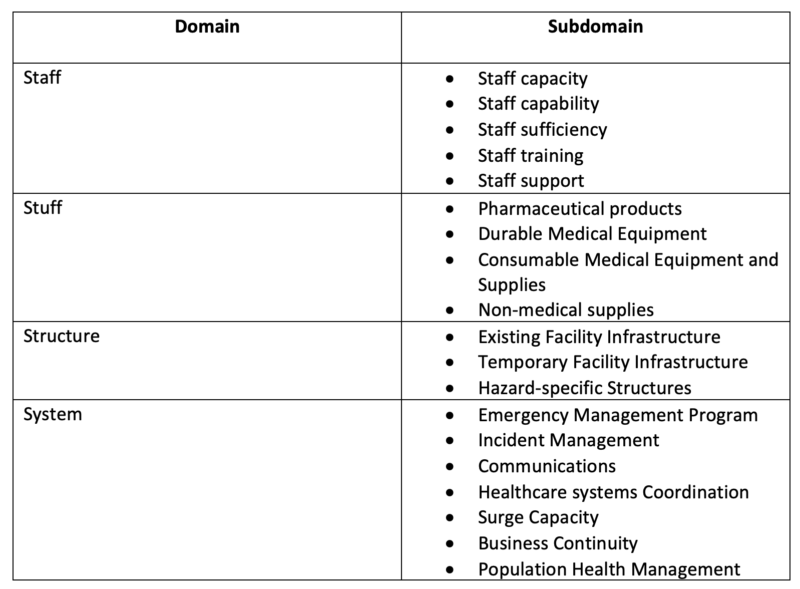

The National Quality Forum in the United States more narrowly describes health care system readiness as an essential element of quality in health systems such that they are prepared for natural disasters and large-scale emergencies[6]. For the purposes of this (non-academic) argument, readiness and resilience can be thought of as two different ways to think about the same general overarching concept. Readiness goes beyond emergency preparedness and is the system’s ability to respond to daily and future stressors and demands on the system. In contrast, resilience can be determined in retrospect: Did the system survive the stressor or demand that was just placed on it? If a system is ready, it will be resilient. The National Quality Forum’s description of health system readiness has four domains: staff, stuff, structure, and systems, as described in Table 1.

Table 1: Four domains of health care system readiness [6]

Have we been “overtaught to be overtaut”?

Back in May, an article about the pandemic in the New Yorker quoted an expert in supply-chain economics as saying that in response to disasters, enterprises have been overtaught to be overtaut.[7] Perhaps one of the greatest lessons to be identified from the pandemic—it remains to be seen whether we have learned it—is that there were/are many vulnerabilities in our acute care system (no surge capacity, single just-in-time supply chains, large human resource gaps, etc.) and our broader health system (under-resourced public health, governance/regulatory/funding shortfalls in long-term care, a lack of integration/coordination between silos, persistent inequities affecting the determinants of health, etc.). Also, these vulnerabilities were usually well known and often perpetuated in the system by choice, policy, or neglect.

Granted, tough trade-offs in systems have to be accepted by the public, policy-makers, and politicians, especially under the constraints present when we entered the pandemic. Addressing all these vulnerabilities in a an increasingly complex system is difficult. But the cost of not doing so is large (and growing). Our over-reliance on reductionistic mental models, siloed decision-making, and command and control management, along with our slavish devotion to so-called efficiency and fiscal sustainability, has contributed to higher rates of COVID-19 infection and deaths compared with countries that were better prepared. [8,9]

The pseudo-efficiency of sailing our health care ship too close to the wind must be balanced with the concepts (and costs) of readiness/resilience. Safe redundancy and surge capacity in complex systems should not be mistaken for inefficiency or dumb duplication. [10] Paradoxically, siloed, sub-system, short-term cost control has cost the whole system dearly over the longer term.10 In the aforementioned New Yorker article the author says, “Efficiency at the cost of resilience is like a silent aneurysm waiting to rupture.”[7]

The triple resilience dividend

Increasingly, there is a human and economic case being made for businesses and governments to invest in system readiness/resilience for the triple dividend that is the return. A report from the World Bank Group describes the first dividend as benefits that are realized when disaster strikes, whereas the second and third dividends occur regardless of disasters or crises (see Figure 1). [12]

Figure 1. The three socio-economic dividends of investing in system resilience through disaster risk management strategies.[12]

Reproduced with the permission of the Overseas Development Institute and the World Bank Group. The original document is available at: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/10103.pdf.

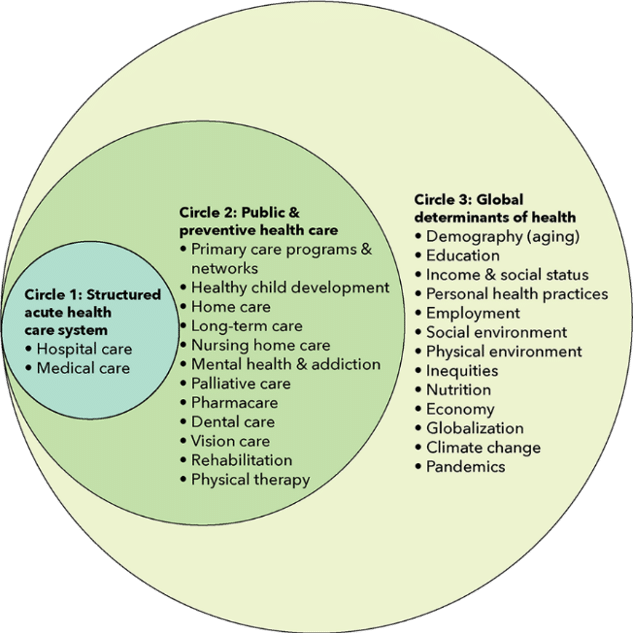

The Canadian Health system has been described as three nested and interdependent sub-systems: 1. The acute care hospital/medical system, 2. The public health, primary care and preventive health system, and the broader global determinants of health and societies boundary conditions contributing to the health of a community. If we aim to improve readiness/resilience in all three areas, it is likely that the system would also see three dividends coming in each area. The first and most obvious benefits would be saving lives and reducing the number of people harmed in the acute care system, as well as avoiding crisis-related staff burnout and infrastructure being overwhelmed during a pandemic or other large-scale health crisis. First-dividend impacts would also be seen in the broader health system as described in a recent annual report from the Public Health Agency of Canada entitled “From Risk to Resilience”. [13]

Figure 2. Elements of health and the Canadian health care system [13]

The benefits of health care system readiness would be seen during good times and bad. The second dividend in this context would be improved system performance during business-as-usual periods. Surge capacity, modularity, and optionality in patient-flow pathways would lead to a significant reduction in hospital access block, ED crowding,[14] and hallway medicine and improve our ability to meet surgical wait-time targets. At the same time, adaptive, self-regulating, and diverse management approaches would lead to an improved environment for innovation and care delivery system integration. [15,16] Furthermore, investing in people also opens the door to opportunities to address many human health resource challenges in our system. [17]

The third dividend of investing in resilience would be the benefits seen beyond the health system itself. Having resilient health systems becomes “part of the competitive advantage of nations” or, at least, of provinces/regions. [1] I wonder whether the Atlantic bubble could lead Canada in this strategy. Arguably, a resilient health care system becomes a catalyst for business development, social innovation, population growth, and economic stability—especially in an era of work-from-anywhere connectivity for some sectors of the economy.

Importantly, however, investing in readiness/resilience does not eliminate the simultaneous need for managing the system with efficiency and for effectiveness. [18] It cannot be either efficiency or readiness; it must be both/and. [19] Therein lies the challenge, and the potential brilliance, but it is clear from our challenges during the ongoing pandemic that just-in-time, single-source supply chains are fragile, and just-enough capacities for hospital beds and health human resources are not enough (and never really were). Our systems have tipped too far to the side of efficiency, leading to the hard realization that this makes complex systems such as health care more costly and unsustainable in the long run. “Never again” has been a common refrain, but what will that mean? The devil is in the details. The divine is in the design.

The Quadruple Aim for redesigning a better health care system

How does a health care system invest in readiness/resilience? Practically, what does it look like at the various levels and scales of health and health care systems? Where do we start?

One thing we know is that there should not be a one-size-fits-all approach. [20] One possible strategy is to add readiness/resilience to the Triple Aim (1. patient experience, 2. population outcomes, and 3. per capita costs), as articulated by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. [21] Readiness has long been the fourth aim of the US Military Health System (for obvious contextual reasons), while others have recommended that health care provider experience/wellness or health equity should become the fourth aim. [22]

In the context of our post–COVID-19 world, adding readiness/resilience to a reframed Quadruple Aim would arguably capture both the wellness aim for health care workers (as it is embedded in the staff domain of the National Quality Forum vision above6) and the health diversity/equity aim; see the five attributes of the resilience in health care framework in Table 1 and the report from the Public Health Agency of Canada. [6,13] Staff experience and wellness contribute to system readiness. Diversity, inclusion, and equity are not only social justice issues; they also make a complex system more resilient. [23]

The meta-point is that without changing the mental models we all share it will be hard to change the structures and processes in our health and health care systems. And if we don’t change our structures and processes, and continually do so in an adaptive paradigm, we are doomed to get stuck in the rigidity trap and repeat past performances as we react to events as things return to normal. [15,8]

Emphasizing readiness/resilience as part of a Quadruple Aim to health care helps us change our shared mental models. This, coupled with a “simple rules” approach, creates the conditions for the emergence of more resilient and efficient health care systems, during both crises and normal times. [24] Value in health care then becomes Readiness + Patients experience + Outcomes/ Cost. [25]

Again, the devil will be in the details, and each system must adapt iteratively in service of the overarching Quadruple Aim, but following these five simple rules can help create value in health care:

- All stakeholders agree on a set of mutual goals of the system. (Quadruple Aim?)

- The extent to which the goals are being achieved are reported to the public.

- Resources are available to achieve the goals. (Investing in the triple dividend of resilience?)

- Stakeholder incentives, imperatives, and sanctions are aligned with the mutually agreed-on goals.

- Leaders of all stakeholders endorse and promote the agreed-on goals and hold themselves and each other to account. [24]

It’s only an idea, and real system change is much messier than that. [25] But it’s a start.

Part 2 of this argument will be a think-out-loud exploration of what the impact of designing post–COVID-19 health care systems with readiness/resilience would mean to emergency medicine. Specifically, it will propose how it could affect what are arguably the four biggest challenges facing the future of emergency medicine:

- Clearly recognizing/supporting the roles and responsibilities of EDs in relation to the broader health care system (enabling the right teams to do the right things in the right locations)

- Addressing the issue of patient access and flow in the system (to eliminate ED crowding)

- Addressing the large (and growing) full-time-equivalency gap in emergency medicine in Canada

- Considering the thorny question of how to optimize the number and distribution of EDs in a given geographical region

This is all possible in a health care system that designs itself with readiness and resilience balanced with efficiency and short-term cost containment.

—Dr. David Petrie

Dr. David Petrie is an emergency physician and trauma team leader at the QEII Health Sciences Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He is also a professor in Dalhousie University’s Department of Emergency Medicine. Dr. Petrie’s primary academic interests include the teaching and assessment of critical thinking in medical education and the application of complexity science to health system design.

References for Covid-19 Pandemic Exposes the Importance of Resilience in Health System Redesign

- Deegan P, Lynch K. Five lasting implications of COVID-19 for Canada and the world. BMO Business Strategy. https://commercial.bmo.com/en/resources/business-strategy/five-lasting-implications-covid-19-canada-and-world/. Published April 03, 2020. Accessed Nov 1/20.

- Helbing D. Globally networked risks and how to respond. 2013;497:51–59. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12047.

- Iflaifel M, Lim R.H, Ryan K, Crowley C.Resilient Health Care: a systematic review of conceptualisations, study methods and factors that develop resilience. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20: Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05208-3.

- Kruk M, Myers M, Varpilah T, Dahn B. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. The Lancet. 2015 May 09;385:1910-1920. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)60755-3/fulltext.

- BMJ 2017; 357 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j2323 (Published 23 May 2017)Cite this as: BMJ 2017;357:j2323.

- National Quality Forum. Healthcare System Readiness Measurement Framework. 2019 June. Available from: https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2019/06/Healthcare_System_Readiness_Final_Report.aspx.

- Mukherjee S. What the Coronavirus Crisis Reveals about American Medicine. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/05/04/what-the-coronavirus-crisis-reveals-about-american-medicine. Published April 27, 2020. Accessed May 4/20

- Van Aerde J. The health system is on fire — and it was predictable. Can J Physician Leadership 2020;7(1):43-51.Available from: https://cjpl.ca/jvafire.html.

- Our World in Data. Emerging COVID-19 success story: South Korea learned the lessons of MERS. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-south-korea. Published June 30, 2020. Accessed July 10/20.

- Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder. Random House; November 27, 2012: ISBN 1-400-06782-0

- COVID-19 stimulus package by country. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1107572/covid-19-value-g20-stimulus-packages-share-gdp/. Accessed Dec 3/20

- Tanner T, Surminski S, Wilkinson E, Reid R, Rentschler J, Pajput S. The Triple Dividend of Resilience Realising development goals through the multiple benefits of disaster risk management. Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) at the World Bank and Overseas Development Institute (ODI). 2015. Available from: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/10103.pdf.

- Tam T. From Risk to Resilience: An equity approach to COVID-19. Government of Canada. 2020 Oct. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19/cpho-covid-report-eng.pdf.

- Petrie, DA, Comber, S. Emergency Department access and flow: Complex systems need complex approaches. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26:1552–1558. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13418.

- Uhl-Bein M, Arena M. Complexity leadership: Enabling people and organizations for adaptability. Organizational Dynamics. 2017;46:9-20. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0090261616301590.

- Naylor D, Fraser N, Girard F, Jenkins T, Mintz J, Power C. Unleashing Innovation: Excellent Healthcare for Canada: Report of the Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation. Government of Canada. 2015 July. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/canada/health-canada/migration/healthy-canadians/publications/health-system-systeme-sante/report-healthcare-innovation-rapport-soins/alt/report-healthcare-innovation-rapport-soins-eng.pdf.

- Bourgealut I, Simkin S, Chamberland-Rowe C. Poor health workforce planning is costly, risky and inequitable. CMAJ 2019 October 21;191:E11478. Available from: https://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/191/42/E1147.full.pdf.

- Ridley M. Blending efficiency and resilience. https://mark-ridley.medium.com/blending-efficiency-and-resilience-1ff876e7f0c9. Published February 11, 2019. Accessed Dec 3/20

- Johnson B. Polarity Management: A Summary Introduction. Polarity Management Associates. 1998 June. Available from: https://www.jpr.org.uk/documents/14-06-19.Barry_Johnson.Polarity_Management.pdf.

- Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Ellis LA, Long J, Clay-Williams R, Damen N, Herkes J, Pomare C, Ludlow K. ) Complexity Science in Healthcare – Aspirations, Approaches, Applications and Accomplishments: A White Paper. Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University: Sydney, Australia. 2017. Available from: https://www.mq.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/683895/Braithwaite-2017-Complexity-Science-in-Healthcare-A-White-Paper-1.pdf.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim. 2020. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed Dec 10/20

- Feely D. The Triple Aim or the Quadruple Aim? Four Points to Help Set Your Strategy. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/the-triple-aim-or-the-quadruple-aim-four-points-to-help-set-your-strategy . Published November 28, 2017. Accessed Dec 10/20

- Llopis G. Without Inclusion, Humankind Is Becoming Less Resilient. https://www.forbes.com/sites/glennllopis/2019/06/02/without-inclusion-humankind-is-becoming-less-resilient/?sh=555f11441746. Published June 02, 2019. Accessed Dec 3/20

- Kottke TE, Pronk NP, Isham GJ. The simple health system rules that create value. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E49. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3340212/.

- Porter M. What is the Value in Health Care? N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec; 363:2477-2481. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmp1011024.

- Sustainable Improvement Team and the Horizons Team. Leading Large Scale Change: A practical guide. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/practical-guide-large-scale-change-april-2018-smll.pdf. Published April 11, 2018.

Drs Ovens and Petrie have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Leave A Comment