Topics in this EM Quick Hits podcast

Anand Swaminathan on occult causes of non-response to vasopressors (0:54)

Brit Long & Michael Gottlieb on overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) (7:45)

Sarah Reid on a bronchiolitis update and evolving patterns in the COVID era (12:30)

Hans Rosenberg & Lindsay Cheskes on the management of electrical storm and recurrent ICD shocks in the ED (20:43)

Justin Morgenstern on the top 10 evidence-based countermeasures for night shift workers (27:45)

Podcast production, editing and sound design by Anton Helman; voice editing by Danielle Lewis

Podcast content, written summary & blog post by Brit Long, Raymond Cho and Anton Helman

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A. Swaminathan, A. Long, B. Gottlieb, M. Reid, S. Rosenberg, H. Cheskes, L. Morgenstern, J. EM Quick Hits 29 – Vasopressor Failure, Asplenic Considerations, Bronchiolitis Update, ICD Electrical Storm, Night Shift Tips. Emergency Medicine Cases. June, 2021. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-june-2021/. Accessed [date].

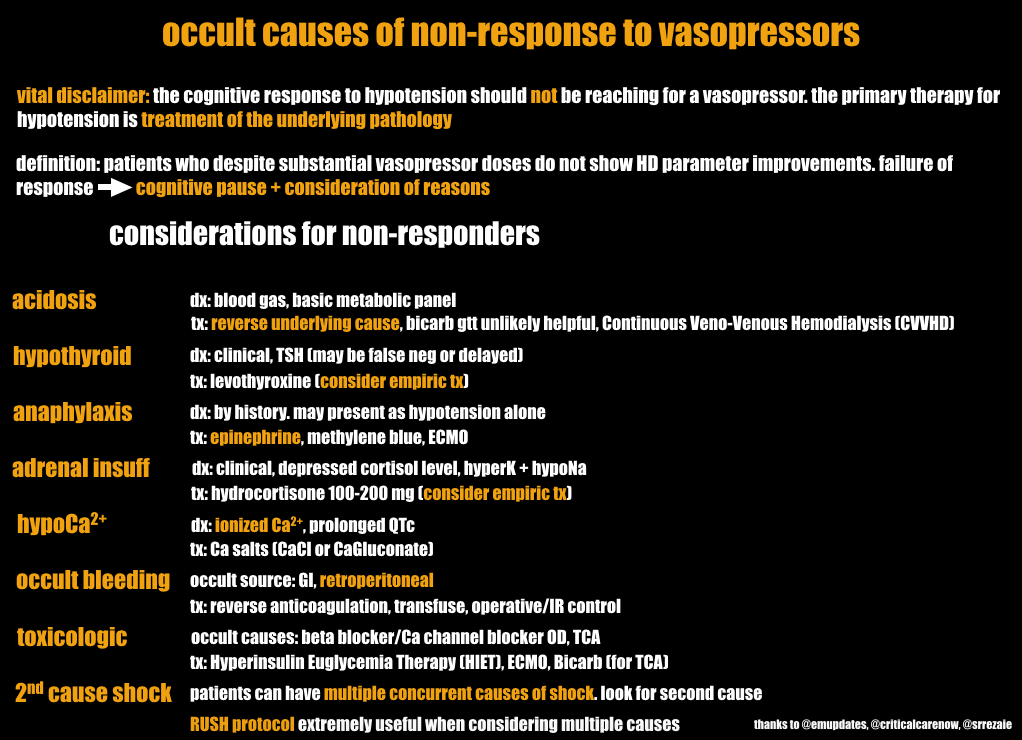

Occult causes of non-response to vasopressors

- Primary therapy for hypotension is to treat the underlying cause, while initiation of vasopressors is a temporary adjunctive therapy

- Despite substantial vasopressor doses, some patients may not respond appropriately with improvements in hemodynamic parameters; failure to respond should lead to a cognitive pause and consideration of the occult causes of non-response to vasopressors.

Occult causes of non-response to vasopressors (source: REBEL EM)

- Anand Swaminathan, “Occult Causes of Non-Response to Vasopressors”, REBEL EM blog, July 13, 2017. Available at: https://rebelem.com/occult-causes-of-non-response-to-vasopressors/.

Overwhelming Post-Splenectomy Infection (OPSI)

Background

- The spleen is integral to normal immune function and overwhelming post splenectomy infection (OPSI) is a potentially deadly infection, which can appear like severe sepsis in a patient with asplenia

- The annual rate of OPSI among asplenic patients is ~0.5%

- Risk factors include young, old and splenectomies performed for hematologic disease

- The most common infections are pneumonia, urinary tract infection, bacteremia, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and meningitis

- S. pneumoniae is the most common microbe causing OPSI, accounting for 40-80% of infections

Clinical assessment

- Fever should be considered a medical emergency in asplenic patients

- Most patients initially present with non-specific symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgias, vomiting, and diarrhea for the first 1-2 days

- They can rapidly decompensate after this with hypotension, septic shock, and multiorgan failure

- Assess for vaccination status, reason for asplenia and source of infection

- Look for a surgical scar and Howell Jolly bodies on peripheral blood smear if their splenic status has not been confirmed

Initial Management

- While evaluating the patient, initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics

- If in shock, administer fluids and vasopressors

- Stress dose steroids may be needed if no response to vasopressors

- Long B, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M. Complications in the adult asplenic patient: A review for the emergency clinician [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 26]. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;S0735-6757(20)30191-1.

RSV Bronchiolitis update and evolving patterns in the COVID era

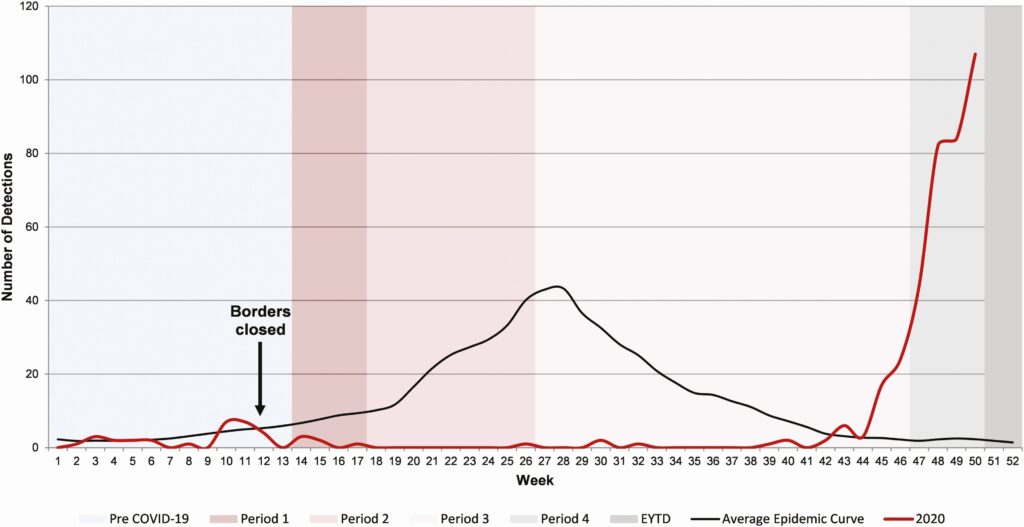

Bronchiolitis evolving patterns

- RSV bronchiolitis is the most common reason for a child under 1 year to be admitted to hospital in Canada but was virtually non-existent during the peak of the COVID pandemic

- There was a recent warning from Australia about off-season bronchiolitis with very significant resurgence during their summer in 2020

- Foley and colleagues published data from Western Australia showing the RSV epidemic curve in 2020 – very low through the weeks where public health measures were in place and then rising rapidly during the summer, which is much higher than usual and with an older mean age of 18 months; the authors suggest that an expanded cohort of RSV naïve patients may be driving this resurgence

- Another study published by Baker et. al. in December 2020 models the impact of the COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on the future dynamics of endemic viruses like influenza and RSV; their results also suggest that a buildup of susceptibility due to public health measures may result in large outbreaks and that RSV may reach its peak in North America in winter 2021-2022

RSV detection in children from metropolitan Western Australian up to week 50 of 2020 (source: Clinical Infectious Diseases)

Bronchiolitis management refresher

- Clinical assessment and diagnosis

- Bronchiolitis is a clinical diagnosis based on patient age, time of year (may be off-season) and clinical presentation

- Typically, a child under 1 year of age who has a URTI prodrome then develops LRTI symptoms with increased work of breathing, crackles and wheezes

- Acute symptoms generally last 10 days but cough/congestion can continue for 3-4 weeks

- Routine CXR for bronchiolitis is not recommended as this often leads to unnecessary antibiotics

- Viral testing is indicated for patients who are being admitted only

- COVID does not appears to be a significant cause of bronchiolitis-like symptoms in children

- Management – mainstay is supportive care

- Supplemental O2 if sats < 90%

- Gentle nasal suction if less than 4 months old (obligate nose breather)

- PO/NG/IV rehydration as needed

- No routine nebulized treatments recommended but consider trial of epinephrine nebulizer if moderate/severe distress

- No role for steroids at present

- Approach to wheezing child over 12 mos

- Trial of asthma therapy (salbutamol) and post assessment

- If it helps then treat them as a young asthmatic per asthma guidelines (i.e. salbutamol, ipratropium, steroids)

- If no improvement with salbutamol, presume bronchiolitis and manage supportively

Bottom Line: Yearly patterns of wheezing illness in children will likely change over the next year; RSV bronchiolitis may present out-of-season, longer and more difficult to manage.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2014, November 1). Clinical practice guideline: The diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/134/5/e1474

- Baker, R. E., Park, S. W., Yang, W., Vecchi, G. A., Metcalf, C. J., & Grenfell, B. T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on the future dynamics of endemic infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(48), 30547-30553.

- Canadian Paediatric Society. (2018, January 31). Bronchiolitis: Recommendations for diagnosis, monitoring and management of children one to 24 months of age. https://www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/bronchiolitis

- Foley, D. A., Yeoh, D. K., Minney-Smith, C. A., Martin, A. C., Mace, A. O., Sikazwe, C. T., Le, H., Levy, A., Moore, H. C., & Blyth, C. C. (2021). The Interseasonal resurgence of respiratory syncytial virus in Australian children following the reduction of coronavirus disease 2019–Related public health measures. Clinical Infectious Diseases.

- Plint, A., & Freire, G. (2020, October). TREKK Bronchiolitis Bottom Line Recommendation (2020). TREKK. Retrieved June 9, 2021, from https://trekk.ca/system/assets/assets/attachments/502/original/2021-01-08-Bronchiolitis_v_3.0.pdf?1610662513

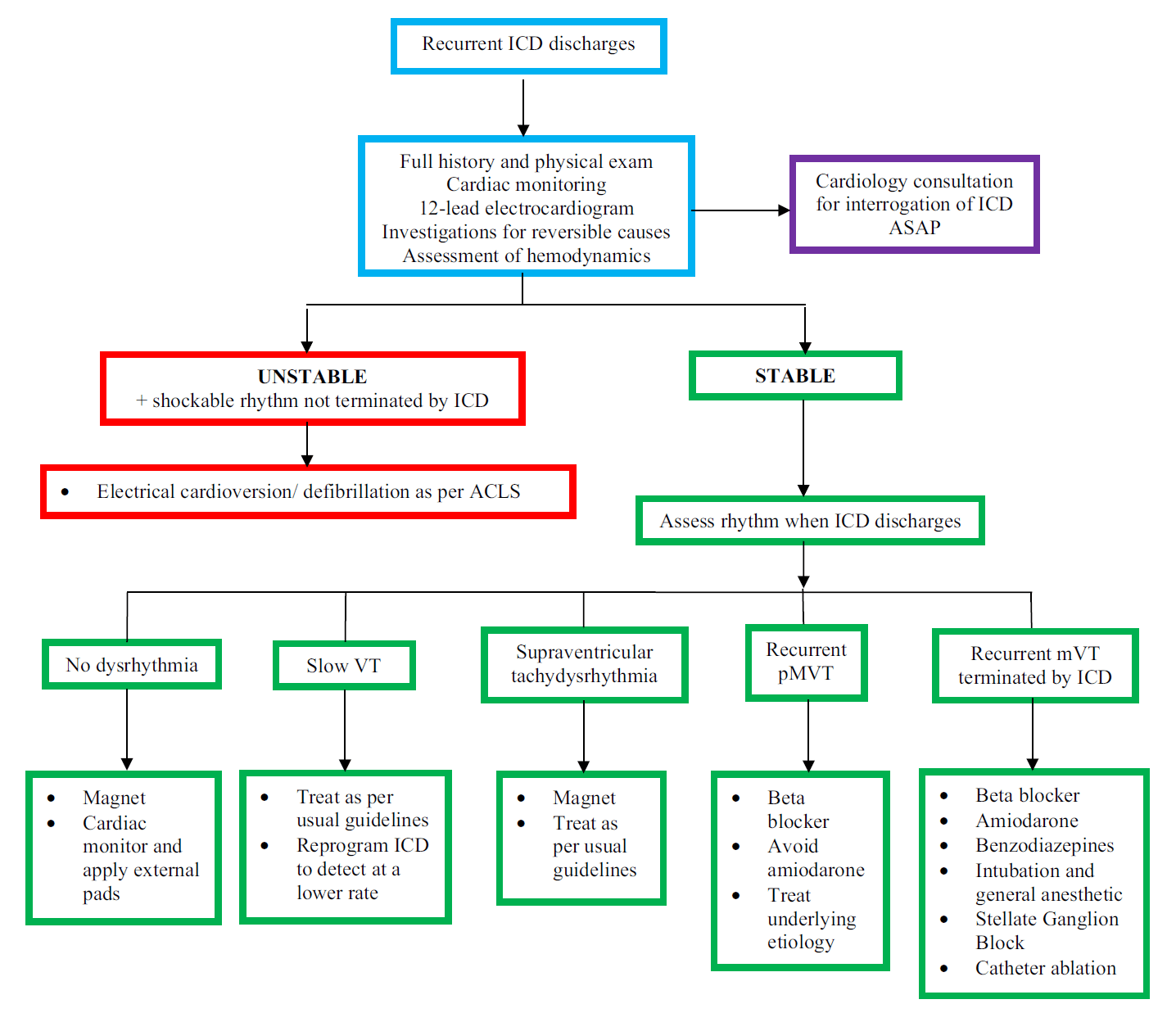

Management of electrical storm and recurrent ICD shocks in the ED

Background

- Definition: 3 or more episodes of sustained VT over 24-hour period or in patients with an ICD, 3 or more appropriate detections of ventricular dysrhythmia that lead to ICD therapy

- Electrical storm is caused by scar-mediated re-entry circuits due to prior myocardial injury

Clinical presentation of electrical storm in patient with ICD

- Pain from ICD discharges, palpitations, syncope or cardiac arrest

- Patients may present with recurrent ventricular tachycardia that is below the ICD therapy threshold (typically < 170-200 beats/min for primary prevention)

- Determine whether ICD therapy is appropriate: appropriate ICD therapy refers to ICD therapy delivered for malignant ventricular dysrhythmia (i.e. VT or VF) while inappropriate ICD therapy is one delivered for non-malignant causes, which accounts for 30% of all ICD therapies

Approach to management of electrical storm in patient with ICD

Approach to assessment and management of recurrent ICD discharges in the ED (source: CJEM)

- Cheskes L, Krywenky A, Sadek MM. Just the facts: management of electrical storm and recurrent ICD shocks in the emergency department. CJEM 2021;23: 147-149.

Top 10 evidence-based countermeasures for night shift workers

- Schedule for circadian rhythm – sequential shifts should move later in the day, minimize transitions between shifts (i.e. all mornings one week, all afternoons the next), work maximum 2-3 night shifts in a row and cap night shifts at 8 hours

- Short (15 minute) nap prior to night shifts (longer naps may lead to increased grogginess)

- Take a short nap if you can on shift

- Maximize bright light on shift: to keep awake and alert while on shift

- Drink caffeinated beverages early in the shift (avoid in the last 4 hours of shift)

- Avoid large carbohydrate-heavy meals before and during shift as they may increase fatigue

- Minimize light (especially blue light from screens) on commute home and before sleeping

- Consider melatonin (studies suggest improvement of daytime sleep by an average of 24 minutes)

- Sleep in a dark, cool and quiet room (consider blackout blinds on windows, eye mask, soundproofing walls, white noise machine, silicone ear plugs)

- Wallace PJ, Haber JJ. Top 10 evidence-based countermeasures for night shift workers. Emerg Med J 2020;37: 563-564.

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare

Leave A Comment