Welcome to the (fairly) new EM Cases CritCases blog, a collaboration between Mike Betzner, the STARS air ambulance service and EM Cases’ Michael Misch and Anton Helman! These are educational cases with multiple decision points where there is no strong evidence to guide us. Various strategies and opinions from providers around the world are coalesced and presented to you in an engaging format. Enjoy!

Written by Michael Misch; Edited by Anton Helman; Expert Peer Review by Dave MacKinnon, Trauma Team Leader, St. Michael’s Hospital. June, 2016.

The Case:

You are the transport physician on call. A 50-year old male with a history of depression allegedly shot himself in the chest with a rifle. A bystander called 911. The local paramedics are en route and the air transport team is activated

What resources would you call upon to prepare for this GSW to the chest patient?

Consider the resources of both your transport team and the rural hospital. The transport team in this case has 2 units of red cells available, however this patient is very likely to require a massive transfusion protocol as well as operative intervention. Ideally you would notify the sending hospital to call for additional red cells from the hospital lab or blood bank as well as a local surgeon or anesthetist at this rural hospital (if available) to help stabilization prior to transfer. Additionally, this patient may require a thoracotomy. A thoracotomy tray is unlikely to be available in this small rural hospital.

I would bring MacGyver Thoracotomy equipment… a suture tray (has big scissors on it and suturing equipment), a big scalpel, and an assistant to hold the chest open.

-Dr. David Lendrum MD M.Ed. FRCPC

Abbreviated thoractomy tray on EM Crit

If you don’t have a rib spreader, go with the manual technique. You only need three things: chlorhexidine, a scalpel and a pair of hands! I have had the good (or bad) luck to do three thoracotomies on my own and have used this approach. Simply douse the patient in chlorhexidine, cut from the sternum to as far down the lateralside as possible – giving the patient a huge chest “gill”. You then just grab the ribs with your hands and pull the chest open. If you don’t get enough exposure you haven’t given the patient a big enough gill. This method is lightning fast and frees your rather tense mind from worrying about how to orient the rib splitter and other stuff in the thoracotomy tray.

-Phil Ukrainetz MD FRCPC

Expert Peer Review

I agree with bringing a thoracotomy tray or suture tray. It’s not ideal to do an ED thoracotomy if there are no Trauma Surgery capabilities on site, but I wouldn’t totally rule it out. Thoracotomy is most likely beneficial with a stab wound, which will have a “clean cut” injury and not the shear injury associated with GSWs.

Now that you have prepared for this GSW to the chest patient, what are your plans in anticipation of the following:

- If he is stable with a GSW to the chest?

- If he has a hemo/pneumothorax?

- If he has a co-ingestion and requires intubation?

- If they are doing CPR when you arrive?

If he has a stable GSW to the chest with no compromising pneumo or hemothorax, I’d keep the [helicopter] blades running and have the patient brought to the helipad to keep the out of hospital time as short as possible….time to surgeon is the number one predictor of survival here in my opinion.

–Mike Betzner MD FRCPC

Case Continued

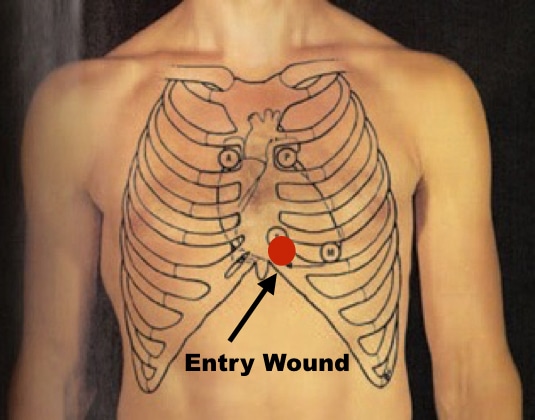

When you arrive, your patient is lying supine on the trauma bed. Vitals are HR 115, BP 100/55, RR 24, and oxygen saturation 94% on non-rebreather. An 18G IV has been placed in the right AC infusing normal saline. The nurses are attempting to obtain a second IV in the other AC. Your patient’s eyes are open and he responds appropriately to voice commands but is slow respond. Air entry is decreased but present bilaterally, heart sounds are normal, abdomen is soft and non-tender. There are no signs of extremity injury, no neck tenderness or jugular venous distension. There is a 4 mm entrance wound just left of the midline of the chest in the lower sternum.

A portable supine chest X-ray shows a bullet fragment somewhere in the cardiac box. Point of care ultrasound shows absent lung sliding on the left side of the chest. A small pericardial effusion is seen without any signs of tamponade. A FAST exam of the abdomen is negative.

What are your immediate next steps in this patient with a GSW to the chest?

You insert a chest tube on the left, which returns a moderate amount of blood.

Your patient is tachycardic and hypotensive. Their shock index is less than 0.9.

Shock index has been shown to be a marker of critical bleeding following trauma. Your patient requires early blood products and expedited transport to a trauma centre. After 1L of NS has infused, you begin infusing blood products. The transport team has 2 units of red cells, but your patient is likely to require a massive transfusion protocol.

Expert Peer Review

Regarding fluid resuscitation, I would definitely use systolic BP or shock index as a guide to fluid/blood administration. There could be harm in “overfilling” the tank and increasing the amount of bleeding.

A discussion on damage control resuscitation and permissive hypotension on Episode 39: Update in Trauma Literature

The ABC Score to predict the need for Massive Transfusion in Trauma Patients

Multiple scores have been evaluated and validated to predict which trauma patients will require a massive transfusion. The simplest and most widely accepted score is the Assessment of Blood Consumption (ABC) score. It has 4 components:

- Penetrating mechanism

- Positive FAST

- HR > 125

- Systolic BP < 90

A score of 2 or greater is strongly suggestive of the need for a massive transfusion.

Many experts suggest that traditional definitions of massive transfusion protocol based on 10 or more units of PRBCs in a 24 hours period is of limited utility for the practicing clinician assessing an unstable trauma patient. If you have given 3 units of PRBCs in an hour it is likely time to activate your massive transfusion protocol. This threshold has been termed the Critical Administration Threshold (CAT) and has been shown to be highly predictive of mortality, need for massive transfusion and need for surgical intervention.

Would you intubate this GSW to the chest patient prior to transfer?

This question was tweeted garnering 3,456 impressions and 460 engagements. With regard to the timing of intubation, many providers including David Hindle (@BritFltdoc), Ola Orekunrin (@NaijaFlyingDr), Dr. Helgi (@traumagasdoc) and Chris Hicks (@HumanFactOrz) emphasized delaying intubation until absolutely necessary. Dr. Andrew Petrosoniak (@petrosoniak) stated that he definitely would want to assess if tamponade was present and with POCUS beforehand, if an effusion was present, as immediate intubation without resuscitation could kill the patient.

If he looked a little worse, uncooperative / altered with soft BP (which seems likely) then I would opt to intubate after establishing that there is no hemopericardium or pneumo with small doses of ketamine +/- fentanyl. I would push phenyl when passing the tube. Would start blood running prior to intubation if possible.

-Ian Walker MD CCFP-EM

Expert Peer Review

I would be very careful about intubating this patient —- with positive pressure ventilation in the presence of hemopericardium. I’m worried the patient will deteriorate. I’d only intubate if he becomes obtunded and absolutely necessary.

I agree with inserting a chest tube at the rural ED — should be able to put one in and secure it within 3-5 minutes. If the patient becomes more unstable it is very nice to know how much blood is coming out of the chest tube and how fast. Also, it takes tensison pneumothorax right out of the equation. You can insert a chest tube on the side of the bullet wound even without a CXR — I would definitely do it in the penetrating trauma patient who is unstable on arrival before the CXR.

You decide to perform RSI prior to transfer as the patient is becoming agitated and his hemodynamics have not improved. What induction agent will you use?

Ketamine and etomidate are generally favoured drugs for RSI in the hemodynamically unstable trauma patient. Both have been shown to be safe in acutely ill patients and have favourable hemodynamic properties compared to propofol. However, even ketamine can precipitate hypotension in the hemodynamically unstable patient who has depleted their catecholamines. Significant dose reductions of 50% or more of ketamine or any other sedatives are recommended by most experts in the acutely unstable trauma patient, despite a paucity of evidence in the literature supporting this practice.

Expert Peer Review

Agree if you were forced to intubate this patient with hemopericardium (not ideal for the reasons stated above), then ketamine is a good choice. I don’t agree with pushing phenyl during intubation – pressors have never been shown to have benefit in trauma — would just improve the BP reading to make you feel better. If you do care about the BP number, ketamine will usually increase it on its own.

Case Continued

You perform RSI using 0.5 mg/kg ketamine and 1.5 mg/kg of succinylcholine. Two units of red cells are infusing and a left chest tube is in place.

You are now preparing the patient for transport when his repeat blood pressure is 80 mmHg systolic with a pulse of 130 bpm. You attempt to repeat POCUS to re-evaluate the pericardial effusion when the patient loses his pulse.

How do you approach a GSW to the chest patient who has had a cardiac arrest?

Traumatic cardiac arrest should prompt a specific algorithm as in non-traumatic cardiac arrest.

Consider 4 reversible causes of traumatic cardiac arrest

Hypoxia

Hypovolemia

Tamponade

Tension Pneumothorax

⬇️

Bilateral Finger thoracostomies

⬇️

Consider Resuscitative Thoracotomy

Expert Peer Review

You could almost put here intubating a tamponade as a separate category — patients with penetrating traumas and hemopericardium are ideally intubated in the OR — so if the patient is suddenly compromised after intubation, thoracotomy can be done in a more controlled setting with a team better prepared and skilled to do so.

Case Continued

You perform a finger thoracostomy of the right chest to address a possible tension pneumothorax on the right. He remains pulseless.

Should you proceed to a resuscitative thoracotomy?

While the indications for ED thoracotomy are often debated, this patient has become pulseless following penetrating thoracic trauma. Survival in this group is highest compared to non-thoracic or blunt trauma and most would recommend consideration of performing ED thoracotomy in this scenario. Neurologically intact survival may be as high as 10-20%. However, this is based on studies largely from academic trauma centres. Additional consideration should be given to the clinician’s comfort in performing the procedure as well as the risk of exposure to yourself and your staff to blood borne pathogens during the procedure.

It is not unreasonable to fly an open chest in the aircraft – I have done this fixed wing for a 45 minute transport. Prophylactic antibiotics anyone?

-Peter Gant MD FRCPC

Expert Peer Review

I think many factors to be considered when deciding whether to do resuscitative thoracotomy in a rural ED: comfort of the Emergency Physician with the procedure, GSW vs. stabbing (much higher survival for stabs), distance to trauma centre with definitive surgical capacity. Agree that you can transport with an open chest if there is return of spontaneous circulation. The local surgeon can be called but my experience is that it’s often been a long time since they’ve done a trauma OR (depending on the site), that they’re not necessarily comfortable doing the procedure, and feel it’s best to transport as quickly as possible to the nearest trauma centre.

You decide to proceed with a resuscitative thoracotomy. How will you proceed?

Most Canadian emergency physicians not working at a trauma centre will go an entire career without performing this procedure. Several simplified techniques have been proposed. Wise et al (2005) recommends a procedure whereby bilateral finger thoracostomies are extended to allow for a clamshell incision. Following a traumatic arrest, immediate bilateral finger thoracostomies in the 5th intercostal space are performed. If return of spontaneous circulation is not achieved, extend both incisions to the midline for a clamshell incision. The use of a clamshell thoracotomy has been advocated because it better exposes critical intrathoracic structures compared to the left anterolateral incision alone.

ED Thoracotomy Procedure on EMCrit

Clamshell procedure on Trauam.org

Case Continued

A left sided thoracotomy is performed revealing profuse intrathoracic bleeding. The pericardium is difficult to grasp due to the overwhelming volume of blood. You make a vertical incision is made in the pericardium revealing a clot with a clear entry wound in the apex of the heart. You insert a foley and inflated it with 10 cc of saline. You use sutures are to close the hole around the foley with some difficulty, but hemostasis is nonetheless achieved.

You then note blood pooling posteriorly in the pericardium. Further exploration reveals a hole in the posterior ventricle, which is closed in a similar fashion. The bleeding is slowed. Internal cardiac massage is initiated, as there is no longer organized cardiac activity.

The thorax continues to pool with blood. The thoracotomy is converted to a clamshell by extending the incision to the right chest. There is no obvious injury in the right chest. While the aorta is cross-clamped, an entry wound is noted in the aorta proximal to the site of clamping. The surgeon from the community hospital, who is now present, is able to assist with closure of the aorta but profuse bleeding continues.

You discuss with your colleagues in the room regarding further options at this point. The patient has been without vitals for approximately 20 minutes.

You agree to cease further resuscitation and pronounce the patient dead.

The decision to perform a thoracotomy in a GSW to the chest patient

The decision to perform a thoracotomy in this GSW situation is certainly a difficult one. Data regarding the potential rate of neurological intact survival do not take into consideration the rural hospital environment, lack of appropriate tools, and prolonged transport time. Some would argue that in a rural setting, bilateral thoracomoties are sufficient effort for the traumatic cardiac arrest given the likely dismal prognosis with prolonged transport time and lack of resources. Alternatively, given that the loss of vitals was in hospital and the relative young age of the patient, you may be prompted to perform the procedure even if the chance of a good outcome is low. Finally, some have argued that survival to organ donation is a positive outcome from resuscitative thoracotomy that should be considered when deciding to perform this procedure.

Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) may help to inform the decision to proceed to thoracotomy. In a study of 187 patients who underwent thoracotomy, cardiac motion was 100% sensitive and 74% specific for the identification of survivors and organ donors. The likelihood of survival if pericardial fluid and cardiac motion were both absent was zero.

Take-Home Points for GSW to the chest

- Consider early mobilization of any resources provided by the sending hospital including blood products, a surgeon or anesthestist who may aid in stabilization prior to transport.

- Consider the use of the shock index and ABC score to identify high-risk trauma patients and those who will require activation of your massive transfusion protocol.

- Consider delaying endotracheal intubation in GSW to the chest patients, and if rapid sequence intubation is performed in an unstable trauma patient lower the dose of induction agents and sedatives by at least 50%.

- Traumatic cardiac arrest should prompt an algorithmic approach to management including addressing reversible causes, bilateral thoracostomies and consideration of resuscitative thoracotomy.

- Resuscititiave thoracotomy should be considered in patients with penetrating thoracic trauma, especially if CPR is under 15 minutes in duration at the time of the thoracotomy, and if the the wound was made by a knife (as apposed to a GSW), but will also be influenced by your resources to safely perform the procedure.

Dr. Misch, Dr. MacKinnon and Dr. Helman have no conflicts of interest to declare.

For more on Trauma Pearls & Pitfalls download the free eBook EM Cases Digest Vol.1 MSK & Trauma

References

Inaba K, Chouliaras K, Zakaluzny S, et al. FAST ultrasound examination as a predictor of outcomes after resuscitative thoracotomy: a prospective evaluation. Ann Surg. 2015;262(3):512-8.

Fairfax LM, Hsee L, Civil ID. Resuscitative thoracotomy in penetrating trauma. World J Surg. 2015;39(6):1343-51.

Morris C, Perris A, Klein J, Mahoney P. Anaesthesia in haemodynamically compromised emergency patients: does ketamine represent the best choice of induction agent?. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(5):532-9.

Olaussen A, Blackburn T, Mitra B, Fitzgerald M. Review article: shock index for prediction of critical bleeding post-trauma: a systematic review. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26(3):223-8.

Nunez TC, Voskresensky IV, Dossett LA, Shinall R, Dutton WD, Cotton BA. Early prediction of massive transfusion in trauma: simple as ABC (assessment of blood consumption)?. J Trauma. 2009;66(2):346-52.

Savage SA, Sumislawski JJ, Zarzaur BL, Dutton WP, Croce MA, Fabian TC. The new metric to define large-volume hemorrhage: results of a prospective study of the critical administration threshold. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(2):224-9.

Schnüriger B, Inaba K, Branco BC, et al. Organ donation: an important outcome after resuscitative thoracotomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(4):450-5.

Seamon MJ, Haut ER, Van arendonk K, et al. An evidence-based approach to patient selection for emergency department thoracotomy: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(1):159-73.

Sikorski RA, Koerner AK, Fouche-Weber LY, Galvagno SM. Choice of General Anesthetics for Trauma Patients. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2014;4:225-232.

Simms ER, Flaris AN, Franchino X, Thomas MS, Caillot JL, Voiglio EJ. Bilateral anterior thoracotomy (clamshell incision) is the ideal emergency thoracotomy incision: an anatomic study. World J Surg. 2013;37(6):1277-85.

Other FOAMed Resources on Trauma Resuscitation

Dave MacKinnon’s podcasts covering trauma resuscitation part 1, part 2 , a 2013 update in the trauma literature and his Best Case Ever on CPR in Trauma

EM Cases Digest Vol. 1 MSK & Trauma eBook

Massive Transfusion Protocol on Life in the Fast Lane

Massive Transfusion in trauma resus and critical questions on massive transfusion on EM Crit

Emergency Thoracotomy on Life in the Fast Lane

ED Thoracotomy Procedure on EM Crit

Leave A Comment