In this EM Cases CritCases blog – a collaboration between STARS Air Ambulance Service, Mike Betzner and EM Cases, a middle aged woman presents to a rural ED with headache and vomiting, normal vital signs with subsequent status epilepticus and serum sodium of 110 mmol/L. What management recommendations would you make to the rural ED physician, the transport team and in your ED with regards to treatment of seizures, safe correction of hyponatremia, airway management, search for underlying cause and prevention of Osmotic Demyelenation Syndrome?

Written by Jim Brokenshire; Edited by Michael Misch & Anton Helman June 2018

Clinical Case

A 52 year old female is brought by car to a rural ED, presenting with gradual onset worsening generalized headache, nausea and vomiting over the past 4 days. According to her husband, she became increasingly confused over the past 4 hours. Her only sick contact is her daughter with sore throat, and she has not recently travelled.

Past medical history is notable for febrile seizure as an infant. She is on no medications.

Triage Vitals are stable: Temp 35.6, HR 85, BP 127/79, RR 17, SpO2 100% on 2L NP, BG = 9.7, weight = 60kg.

While finishing the triage registration process she has a focal right sided tonic/clonic seizure lasting 1 minute. She is subsequently post-ictal with a GCS of 6 and is brought into the resuscitation bay. Shortly thereafter, she begins to seize again…

What is the differential diagnosis and initial management?

The differential at this point is quite broad. The presentation of progressive headache, vomiting, and altered mental state (and now status epilepticus) should prompt consideration of

- intracranial hemorrhage or mass

- meningitis or encephalitis

- toxicological or metabolic cause

The presence of a sick contact suggests a potential infectious etiology.

Initial management should consist of basic airway maneuvers and establishment of intravenous lines. A capillary glucose is a must – in this case it was initially 9.7 mmol/L. Benzodiazepines are first-line for treatment of status epilepticus..

She is given lorazepam 4 mg IV and the seizure terminates. She remains altered and postictal. A transfer via ground EMS to a tertiary care centre is requested.

As the consulting transfer physician, what are your next steps to facilitate safe transport of this patient?

Given the patient’s neurological status and the need to transport and further work-up, the patient should be intubated. If a paralytic agent is to be used, consider succinylcholine to avoid masking ongoing seizure activity with longer acting agents such as rocuronium. A noncontrast CT head should be arranged to assess for an intracranial mass or hemorrhage. Routine labs and extended lytes, blood gas, toxicologic panel (ASA, Acetaminophen, EtOH, and ECG), and blood cultures should be ordered. A lumbar puncture may be necessary but should not delay transfer. Empiric coverage of meningitis/encephalitis could be considered in the meantime. Loading the patient with an IV anti-epileptic drug (ie. fosphenytoin 15-20 mg/kg IV over 30 mins) should be a priority given that the patient is in status epilepticus.

The following lab values return:

CBC — WBC = 17.3, differential pending

Lytes – Na+ = 110 K+ = 2.6 Cl- = 73 HCO3 = 13

Creatinine = 52 Lactate = 10.7

ASA, Acetaminophen, EtOH all negative.

VBG pH = 7.04 pCO2 = 47 BE = -18 HCO3 = 13

The CT head shows nil acute.

The serum sodium is most strikingly abnormal. What is your differential for this patient’s hyponatremia?

You have identified severe hyponatremia in this patient, which is a likely contributor to her seizure activity. Seizures are relatively uncommon in patients with chronic hyponatremia, but occur in approximately 30% of patients with acute severe hyponatremia. In this case the sodium is extremely low and both acute and chronic causes must be considered. Hyponatremia is not a diagnosis — the differential diagnosis is traditionally categorized based on the patient’s volume status, which may be challenging to assess. Clues to volume status may include history, vital signs (HR, BP, postural drop), POCUS findings, and presence of absence of edema.

| Hypovolemia | Euvolemia | Hypervolemia |

Renal Loss

Extra-Renal Losses

|

SIADH

Hypothyroidism Addisonian Crisis Psychogenic Polydipsia |

CHF

Cirrhosis AKI/Nephrotic Syndrome |

In this patient with preceding vomiting, extrarenal solute loss, SIADH, polydipsia and Addison’s are at the top of the differential.

What symptoms are attributable to this patient’s hyponatremia?

Symptoms of hyponatremia are generally nonspecific. Nausea, irritability and malaise can be seen with acute hyponatremia of 125-130 mmol/L, while acute hyponatremia below 120 mmol/L can result in headache, confusion, lethargy and coma. Symptom severity from hyponatremia depends on two factors: The severity of hyponatremia and the acuity of its onset. As such, someone with chronic hyponatremia can have minimal symptoms with a sodium of 118 mmol/L while someone with an acute drop in sodium over a few hours can be impressively symptomatic at a sodium of 130 mmol/L. That being said, seizures attributed to hyponatremia are unusual in patients with a serum sodium >115 mmol/L.

The patient is no longer seizing but remains obtunded with a GCS of 6. How will you manage this patient prior to transfer?

This patient has severe symptoms of hyponatremia as defined by coma and seizures. They require rapid sodium correction with hypertonic saline. Typical dosing is 3% saline 100 ml IV bolus over 10 min. This may be repeated twice every 10 minutes if symptoms do not improve. If hypertonic saline is not readily available, 2 amps crash cart 8.4% sodium bicarbonate can be substituted. It is advisable to recheck serum sodium within 20 minutes.

What are your treatment goals when giving hypertonic saline?

Hypertonic saline is indicated for neurologic emergencies in the context of hyponatremia (ie. coma or seizures). Some guidelines advocate for its use for moderately severe symptoms such as confusion or headaches but this is controversial. Your goal should be to improve the patient’s symptoms of severe hyponatremia (improved LOC or terminating seizures) or increase serum sodium by 5 mmo/L, whichever comes first. In the severely hyponatremic patient, only small increases in sodium are necessary to achieve clinical improvement. If the serum sodium has increased by 10 mEq/L (or increased to 30 mmol/L) and there is no improvement in clinical status, you should consider other explanations for the patient’s altered mental status.

Clinical Pearl: If the serum sodium has increased by 10 mEq/L (or increased to 30 mmol/L) and there is no improvement in clinical status, you should consider other explanations for the patient’s altered mental status.

Rapid correction of hyponatremia increases the risk of Osmotic Demyelination Syndrome (ODS), previously termed Central Pontine Myelinolysis. Correction of acute hyponatremia should be less than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours but ideally less than 6 mmol/L in this time period. However, ODS is rare, and fear of it should not preclude administering hypertonic saline to symptomatic patients.

“I’d suggest 2-3 amps of Bicarbonate if they don’t have 3% saline available.”

-Ryan Deedo MD DipAeroRT MAvMed FRCPC Flight Physician STARS

The patient is given 2 doses of 100 cc 3% hypertonic saline. They are no longer seizing and are bucking the ventilator. You provide fentanyl for analgesia while en route. Repeat electrolytes are pending. The patient is awaiting plane arrival for the 30-minute transfer.

What are your other management priorities prior to transfer?

The patient needs a foley catheter to monitor urine output as increased urine output greater than 100 ml/hour could herald free water diuresis, which can rapidly overcorrect hyponatremia and puts the patient at risk of ODS.

Adrenal crisis is on the differential for this patient. While adrenal insufficiency typically presents with hyperkalemia, primary adrenal insufficiency can present with isolated hyponatremia and shock. Treatment should be given on speculation with Hydrocortisone 100mg IV or Dexamethasone 4mg IV. The latter would potentially allow for ACTH stimulation testing later in the patient’s care.

Meningitis is on the differential for this patient’s presentation and hyponatremia may just be a manifestation of this via an SIADH mechanism. Thus, empiric antibiotic coverage would be prudent.

This patient has concomitant hypokalemia. Correcting this will facilitate raising the serum sodium. KCl elixir 10 meEq PO/NG x1 would be reasonable.

How will you manage the IV fluids during the 30-minute air transfer?

Following administration of hypertonic saline for coma or seizure, very judicious use of intravenous isotonic fluid is prudent. Further IV fluids should be administered only if the patient is clinically hypovolemic with the goal of restoring intravascular volume. Otherwise, fluid restriction is warranted. Intravenous Ringer’s Lactate may be preferable to Normal Saline, as Ringer’s is more isotonic for the hyponatremic patient. Fluid restriction after initial resuscitation is advisable. If the patient is deemed euvolemic, saline lock the IV.

“My personal practice is much like Rob, to terminate the seizure with HTS in a dose of 50 to 100 cc at a time over 10 min (or to substitute 2 amps of NaHCO3 if that is what is available). I’ve never had to give more than 2 doses of 50 mL of HTS personally.”

-Michael J. Betzner MD FRCPC, Medical Director STARS Calgary

This patient was intubated, transferred, and admitted to ICU at a tertiary care centre. She was treated with Ceftriaxone/Vancomycin/Ampicillin/Acyclovir. Her brain MRI and LP were normal. She diuresed approximately 3 L in ICU within the first 3 hours. Her repeat sodium is 128 mmol/L.

What is your primary concern at this point in this hyponatremia case?

Immediately following the onset of hyponatremia, sodium and water flow into the CSF, compensating for the acute change in tonicity. Within hours, potassium and organic solutes are also excreted to make the brain isotonic to plasma. This process is complete within two days. A subsequent rapid correction following at least two-three days of hyponatremia (often under 120 mmol/L) is thought to subsequently case brain cells to shrink and demyelinate, causing significant morbidity. For this reason, the maximum sodium correction of 10 mmol/L within the first 24 hours is recommended. This patient’s sodium corrected by 18 mmol/L in under 24 hours placing them at risk for ODS. Symptoms of ODS will not develop until 2-5 days later and include dysarthria, paraplegia, movement disorders and coma. A common reason for this rapid overcorrection is in a hypovolemic hyponatremic patient who is resuscitated with IV fluids. Restoration of intravascular volume blocks the release of AHD, which decreases water reabsorption in the kidneys, precipitating free water diuresis and an acute rise in serum sodium.

This is why hyponatremic patient require monitoring of urine output. When urine output exceeds 100 ml/hour, urine osmolality should be obtained. A urine osmolality less than 100 mosm confirms free water diuresis, putting the patient at risk of rapid overcorrection.

What are your immediate next steps?

Consult a nephrologist. While the patient may require an infusion of D5W to replace free water, they will likely need desmopressin (exogenous ADH) to stop further free water diuresis and reverse the overly rapid correction hyponatremia. The typical dose of desmopressin is 1-2 mcg, which can be repeated every 8 hours. Electrolytes should be monitored every 2 hours. This should be done in consultation with a nephrologist or internal medicine specialist.

Case Resolution

The patient is given desmopressin and has regular monitoring of electrolytes and urine output. Following correction of her serum sodium less than 6 mmol/L/day, she improves and when extubated gives a clear history of inappropriately high water intake, attempting to compensate for a viral illness. She was subsequently discharged with a diagnosis of polydypsia without complication.

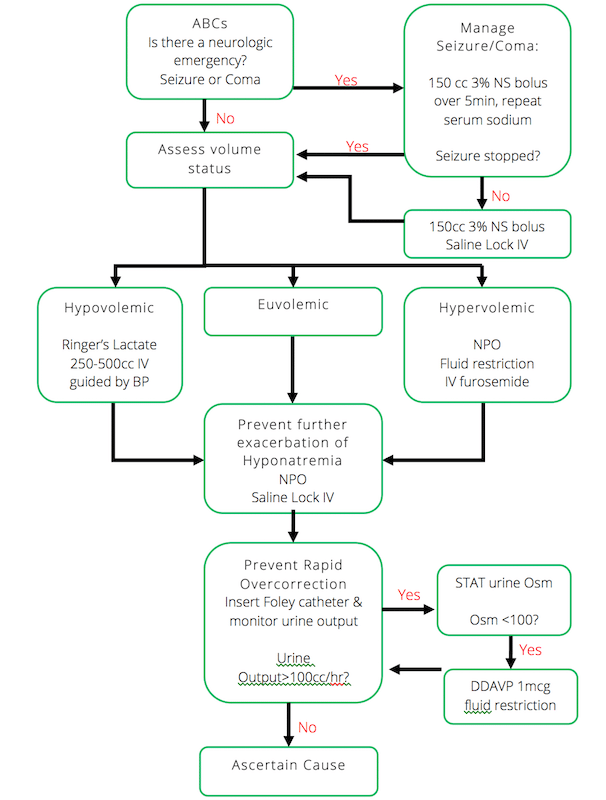

EM Cases hyponatremia management algorithm

Hyponatremia management algorithm by Dr. Ed Etchells, EM Cases Episode 60

Drs. Helman, Brokenshire and Misch have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, et al. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29 Suppl 2:i1-i39. Full PDF

Sterns RH, Hix JK, Silver S. Treating profound hyponatremia: a strategy for controlled correction. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:(4)774-9. Full PDF

Alleman AM. Osmotic demyelination syndrome: central pontine myelinolysis and extrapontine myelinolysis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2014;35:(2)153-9. Abstract

Other FOAMed Resources on Hyponatremia

https://emergencymedicinecases.com/episode-60-emergency-management-hyponatremia/

Hi Anton, I wonder why you used hypertonic saline instead of hypertonic bicarb. despite the presence of PH of 7.04, is it the fear of worsening the hypokalemia or something else?

The patient has a anion gap metabolic acidosis most likely due to an elevated lactate from the seizure. This will rapidly correct itself. There is no non-anion gap acidosis in this case and there is hypokalemia. While 8.4% bicarbonate will likely actually briefly increase the serum K due to solute drag, it will induce a metabolic alkalosis in this patient once the lactic acidosis is cleared. Therefore I think there isn’t much rational to use 3% saline over 8.4% NaHCO3 if it’s a small volume and used to emergently raise the Na level. If for example, the patient’s VBG was pH 7.04, pCO2 47, HCO3 13 and chemistry showed Na 110, Cl 78 (instead of 72), lactate 5.7, and HCO3 13, then there would be a theoretical advantage to using 8.4% NaHCO3 over 3% saline, as the sodium bicarbonate would simultaneously treat the hyponatremia and non-anion gap metabolic acidosis, whereas the 3% saline would worsen the NAGMA.