Topics in this EM Quick Hits podcast

Yaron Finkelstein on pediatric cannabis poisoning pitfalls

Brit Long on recognition and management of esophageal perforation

Jesse McLaren on 3 questions to diagnose Brugada Syndrome

Tahara Bhate on QI Corner – we don’t want to give anything away for this one!

Constance Leblanc on maintaining wellness in career transitions

Podcast production, editing and sound design by Anton Helman

Podcast content, written summary & blog post by Hanna Jalali and Brit Long, edited by Anton Helman

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A. Leblanc, C. Bhate, T. McLaren, J. Ling B. Finkelstein, Y. EM Quick Hits 43 – Pediatric Cannabis Poisoning, Esophageal Perforation, Brugada, Career Transitions in EM. Emergency Medicine Cases. October, 2022. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-january-2019/. Accessed April 23, 2024.

Pediatric cannabis poisoning – The Best of U of T EM Series

Since cannabis legalization in Canada there has been a 9-fold increase in pediatric ED presentations due to accidental cannabis ingestion, corresponding with a marked increase in hospitalization.

There are currently two peaks at age of ingestion seen:

- Toddlers (largely due to visually attractive edible cannabis that is now widely available)

- Teenagers (largely due to increased acceptability and availability)

The diagnosis of cannabis poisoning can be challenging in some pediatric patients and without a clear history patients undergo many invasive tests and procedures (i.e., CT, LP) in order to assess for the cause of their symptoms.

Factors contributing to diagnostic challenge in pediatric cannabis poisoning:

- Delay to onset of symptoms: In young children, the effect of THC is not seen for 30-60 minutes until it is absorbed through the blood-brain barrier. Children will continue to consume cannabis if it is accessible during this delay.

- Parents withholding information: Parents may fear the legal implications of admitting the ingestion to healthcare providers.

- There is no toxidrome: The clinical picture of cannabis poisoning is quite broad, and can mimic many other conditions including meningitis, encephalitis, non-accidental injury, or brain malignancy.

The clinical spectrum of pediatric cannabis poisoning:

Currently, there is a mixed picture of how our pediatric patients present. Many have a benign course, and after a short observation period can be discharged home. However, for those patients that have a larger ingestion, or more severe response possible presentations include:

- Altered LOA: e.g.”sleepier”, more difficult to rouse, coma with a GCS of 3

- Gait disturbance

- Seizures

- Hypothermia

- Apnea

Treatment of pediatric cannabis poisoning

- Many patients will only need a period of observation and discharge after they have returned to baseline.

- Others will require supportive care until cannabis is cleared from their system including:

- IV insertion and fluid management if they are too obtunded to maintain their intake

- Monitoring for glucose, electrolytes, and hypothermia

- Intubation required by GCS or if apneic

- Benzodiazepines for those presenting with seizures

- There is little role for GI decontamination as the clinical manifestations of pediatric cannabis poisoning are delayed beyond the time that GI contamination may be effective

Decreasing cannabis poisoning rates—a public health perspective

- Provinces that legalized edibles prior to others saw a dramatically increased rate of children with cannabis poisoning requiring hospitalization. There is a role for legislation to play in monitoring and control of edible cannabis (e.g. decreasing the maximum amount per package).

- We, as educators, need to ensure that parents are aware that cannabis ingestion can be dangerous and to safely store cannabis as one would any other medication.

- Myran, D. T., Tanuseputro, P., Auger, N., Konikoff, L., Talarico, R., & Finkelstein, Y. (2022). Edible Cannabis Legalization and Unintentional Poisonings in Children. The New England journal of medicine, 387(8), 757–759.

- Richards JR, Smith NE, Moulin AK. Unintentional Cannabis Ingestion in Children: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr. 2017 Nov;190:142-152.

- Myran DT, Cantor N, Finkelstein Y, Pugliese M, Guttmann A, Jesseman R, Tanuseputro P. Unintentional Pediatric Cannabis Exposures After Legalization of Recreational Cannabis in Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Jan 4;5(1):e2142521.

Esophageal perforation – one of the “big 5” life-threatening causes of chest pain that is sometimes neglected

In our patients presenting with chest pain, we often consider ACS, aortic dissection, and PE. However, it is important to include the rarer esophageal perforation in your differential diagnosis for any patient presenting with chest pain.

Esophageal perforation is a full thickness tear through the esophageal mucosa and muscle due to a sudden increase in intraesophageal pressure. When this occurs there is extravasation of gastric contents into the mediastinum which causes mediastinitis and systemic infection with a mortality rate approaching 90%.

Classically, we think of the Boerhaave’s Syndrome triad: vomiting, followed by chest pain, and lastly subcutaneous emphysema. However:

- Only 15% of esophageal perforation is due to Boerhaave’s syndrome

- Of those Boerhaave’s cases, only 50% of them present with the triad

- Vomiting is present in less than 50% of esophageal perforation

Consider risk factors for esophageal perforation

- Prior esophageal disease

- Recent endoscopic procedure

- Causes for increased intraesophageal pressure including, but not limited to, vomiting (extreme exertion, seizures, childbirth, and prolonged coughing)

History and exam findings of esophageal perforation

- Pain – may not be limited to chest pain (i.e., peritonitis in distal perforation with leakage into the abdominal cavity)

- Fever – 40-50% of cases

- Subcutaneous emphysema – present in 60% of patients and often delayed.

- Hamman’s crunch – crunching sound synchronous with each heart that may occur with mediastinal emphysema

- Systemic symptoms – often delayed and may not be present on initial presenation

- Abnormal breath sounds on the left due to effusion or pneumothorax

Diagnosis of esophageal perforation

CT chest with IV contrast or CT esography are both highly sensitive. CT chest is usually more readily available and may provide you with an alternative diagnosis. The chest x-ray is also abnormal in about 90% of cases possibly showing pneumomediastinum or subcutaneous emphysema. PoCUS may show effusion, pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, or difficulty visualizing the heart if there is air in the mediastinum.

ED Treatment of esophageal perforation

- Resuscitate the patient as per usual CABs

- Broad spectrum antibiotics: piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin or meropenem and vancomycin

- Anti-emetics and analgesia

- PPI infusion

- Involve your consultants early including thoracic surgery, gastroenterology, IR, and ICU as these patients can have varying levels of perforation and there are different treatment options that may require collaborative care. Ask your specialists to insert an NG tube.

- Consider a chest tube if there is a large amount of gastric content in the chest especially if there is a delay with getting the patient to the operating room.

Airway consideration in patients with esophageal perforation

- If the patient is hemodynamically unstable or in respiratory distress, they likely need a definitive airway so consider this early.

- Be careful with administration of non-invasive ventilation as this can increase subcutaneous air and make it challenging to obtain a definitive airway later.

Summary: Esophageal perforation is a potentially deadly diagnosis that we cannot miss. Do not rely on the classic triad of vomiting, chest pain and subcutaneous emphysema to consider the diagnosis. Look for risk factors in any patient presenting with neck, chest or abdominal pain and get a CT chest with contrast if you suspect it. Treat with supportive care, broad spectrum antibiotics and get your specialists on board early.

- DeVivo, A., Sheng, A. Y., Koyfman, A., & Long, B. (2022). High risk and low prevalence diseases: Esophageal perforation. The American journal of emergency medicine, 53, 29–36.

- Long, B. (2022, September 20). EmDOCs podcast – episode 62: Esophageal perforation/rupture. emDOCs.net – Emergency Medicine Education. Retrieved October 9, 2022, from http://www.emdocs.net/emdocs-podcast-episode-62-esophageal-perforation-rupture/

The 3 questions to diagnose Brugada Syndrome

Brugada syndrome is a sodium channelopathy that is temperature sensitive and causes an ECG pattern in the right ventricular leads (V1-V2) that is made worse with fever or sodium channel blockade. Brugada syndrome can lead to syncope or sudden cardiac death that can be prevented with an ICD. Making this diagnosis can save a life. To make the diagnosis, there are 3 questions that you must ask yourself.

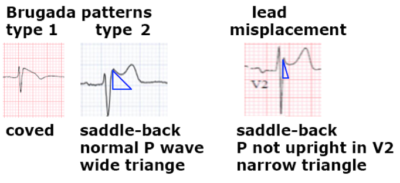

Question #1: Does the ECG have a Brugada pattern?

Type I: RS complex followed by a coved ST elevation that descends and ends into inverted and symmetric T wave. This is specific for Brugada pattern.

Type II: is RSR’ with saddleback ST elevation and positive T wave. This type can be seen with lead misplacement or normal variants.

- P waves are normally biphasic in V1 and fully upright in V2. If p wave is negative in V1 or not fully upright in V2 then the leads are too high which can produce an RSR’ pattern with ST elevation, this resolves with appropriate lead placement.

- If the P waves are as they should be, then draw a triangle with the peak at the R’ and base 5mm below. If the base is wide (> 4mm) this identifies Type II Brugada pattern. If the base is narrow, then this is a normal variant.

Question #2: If there is a Brugada pattern, is this a Brugada phenocopy/mimic?

Brugada phenocopies are reversible clinical conditions unrelated to fever or sodium channel blockade that can mimic Brugada pattern. This includes metabolic conditions that alter conduction (hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia, hypothyroidism, hypothermia), mechanical compression of the right ventricle (i.e., due to tension pneumothorax), V1-V3 ischemia (anterior infarct, PE), or myo/pericarditis. Once these conditions are treated the Brugada pattern should resolve.

Question #3: Does the patient have Brugada Syndrome?

If there is a confirmed Brugada pattern, and no evidence of a phenocopy the diagnosis of the syndrome requires that Type 2 converts to Type 1 with use of sodium channel blockers, or for the initial presence of type 1. Management of the syndrome depends on symptoms including syncope, nocturnal agonal breathing, or resuscitative arrest. Patients that have any of these require referral for ICD, whereas those incidentally found can be referred to electrophysiology. All patients should be instructed to treat fevers aggressively and avoid sodium channel blockers.

In summary, ask yourself these 3 questions:

- Is there a Brugada pattern or is this lead misplacement/normal variant?

- Are there any reversible causes that could lead to Brugada phenocopy?

- Does the patient have symptoms that fit diagnosis of the syndrome and need ICD, or do they just need a referral to electrophysiology?

- McLaren, J. (2022, July 19). Sudden cardiac death – brugada syndrome: ECG cases: EM cases. Emergency Medicine Cases. Retrieved October 9, 2022, from https://emergencymedicinecases.com/brugada-syndrome-3-step-approach/

- Brugada P and Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J of Am Coll Cardiol 1992 Nov 15;20(6):1391-6

- Bayes de Luna A, Brugada J, Baranchuk A, et al. Current electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of brugada pattern: a consensus report. J Electrocrdiol 2012;45:433-442

- Baranchuk A, Enriquez A, Garcia-Niebla J, et al. Differential diagnosis of rS’ pattern in leads V1-V2: comprehensive review and proposed algorithm. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2015;20(1):7-17

- Anselm D, Gottschalk B, Baranchuk A. Brugada phenocopies: consideration of morphologic criteria and early findings from an international registry. Can J of Cardiol 2014;20:1511-1515

- Brugada J, Campuzano O, Arbelo E, et al. Present status of Brugada syndrome: JACC state-of-the-art review. J of Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72(9):10461059.

QI Corner

Identify near-miss events in your ED and analyze them for areas of improvement. A near-miss event is a threat to patient safety that through timely intervention or sheer luck did not result in harm to the patient. Many incidents of harm are preceded by this and are opportunities to improve.

- Respect the altered older patient and cast your diagnostic net wide. Hemodynamics may not reflect the severity of illness.

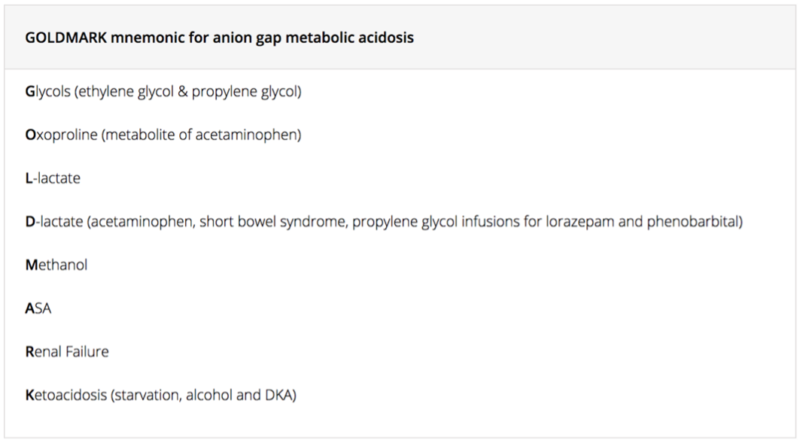

- Update your approach to metabolic acidosis (Consider the GOLDMARK mnemonic for non-anion gap metabolic acidosis – see below).

- Euglycemic DKA is easy to miss and should be included in your differential diagnosis of anion gap metabolic acidosis; check the medication list for SGLT2 inhibitors.

- Communicate your sense of urgency or priority to your team of investigations and treatments needed for your patient.

- When possible, use translation resources. This may take extra time but can turn the management of the case and help you understand the baseline of your patient.

Systems factors that may contribute to near misses and poor outcomes with potential solutions

Currently, our emergency departments are experiencing challenges with hallway medicine, staff shortages, and access block that may be out of our immediate control. However, identify actionable items within your ED that can be changed to improve care after discussion with staff:

- If time to physician assessment is long, consider a physician at triage or EP Lead

- If time to start investigations on hallway patients is too long, consider a laboratory technician at triage that can start orders

- Consider rounding on hallway patients 1-2 times per shift, especially overnight so that you can pick up on any patients that have deteriorated from triage.

- Mehta AN, Emmett JB, Emmett M. GOLD MARK: an anion gap mnemonic for the 21st century. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):892.

Maintaining wellness in career transitions – highlight from CAEP 2022

There are multiple transitions in your career and personal life that may include transition to practice, transition to parenthood, transition from illness, to transitioning to retirement.

Some suggestions to help manage these transitions:

- Be open to being mentored and providing mentorship yourself

- Recalibrate expectations about being perfect. Some responsibilities need to be delegated, delayed or even neglected while you prioritize others

- Be okay with being buddied up and asking for double coverage; always ask for help when you need it

- Incorporate time for transition when you will have new responsibilities; expect that you will need extra time and help during those times

- Be open to new opportunities and say yes when you can; however, especially later into your career remember to also be selective and reflect on what you and the people depending on you need as well

- Involve collaborators and/or mentees on projects with you for your own learning, as a helping hand, and to help your future colleagues.

In general, plan for transitions in your career and connect yourself with people that will ease these transitions for you. Find a passion and maintain your curiosity, but do not set unrealistic expectations. Remember that sometimes we might need extra training or work slowly towards something. Be patient with yourself and ask others what they needed for specific transitions within their career. Most importantly, have a welcoming attitude towards any transitions; ultimately, they are opportunities for growth, learning, and change which as emergency physicians we generally thrive on.

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare

Hi, at the beginning of the episode you mentioned quizzes based on the subjects discussed above. However, I don’t see where to take those quizzes? I’ve logged on and went into the quiz list, but don’t see any quizzes related to above. Am I looking in the wrong location for quizzes related to these “quick talks”

Thanks all.

Quizzes are for the main episode podcasts only (not the EM Quick Hits series)