Topics in this EM Quick Hits podcast

Anand Swaminathan on recognition and ED management of adrenal crisis (00:33)

Maria Ivankovic on indications for antibiotics in strep throat from EM Cases Course 2020 (7:13)

Jesse McLaren on recognition of posterior MI from ECG Cases (10:37)

Justin Yan & Hans Rosenberg on just the facts of approach to DKA (18:24)

Brit Long on ovarian torsion imaging myths (23:24)

Walter Himmel on how to use the HINTS exam properly (29:21)

Ian Stiell on how to use Canadian CT head rules properly (36:08)

Podcast production, editing and sound design by Anton Helman

Podcast content, written summary & blog post by Sucheta Sinha, Brit Long, edited by Anton Helman

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A. Swaminathan, A. Long, B. Rosenberg, H. EM Quick Hits 14 – Adrenal Crisis, Strep Throat, Posterior MI, DKA Just the Facts, Ovarian Torsion Imaging, HINTS Exam, Canadian CT Head Rule. Emergency Medicine Cases. April, 2020. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-march-2020/. Accessed [date].

Adrenal crisis recognition and ED management

- Adrenal crisis results from an acute deficiency of adrenocortical hormones which carries a significant mortality rate if not recognized early and managed aggressively

- The hallmark is severe hypotension/vasodilatory shock refractory to IV fluids and vasopressors

- Other diagnoses to consider in patients with fluid and vasopressor refractory shock include B-blocker overdose, calcium channel blocker overdose, anaphylaxis, hypocalcemia, cardiogenic shock, occult bleeding, severe hypothyroidism

- Diagnosis is challenging as symptoms are highly variable and non-specific, which may include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, weakness, confusion or fever, however a presumptive diagnosis can be made if the patient responds to IV steroid therapy within 1-2hrs

- Adapt a cognitive forcing strategy to think of adrenal crisis in patients suspected of septic shock who are not responding to treatment as expected, as shock and fever may be the only signs, especially in those with pre-exististing adrenal insufficiency (e.g. Addison’s) and in those with a history of steroid medications use

- Lab clues include hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, non-anion gap metabolic acidosis, low bicarbonate, elevated BUN/creatinine, however these are neither sensitive nor specific

- Hydrocortisone 100mg IV bolus, then 25 mg IV hydrocortisone IV q6hr is the preferred initial treatment for most patients

- Dexamethasone 4-6 mg IV may be considered for those with pre-existing adrenal insufficiency as dexamethasone does not interfere with measurement of cortisol levels

- Treat the underlying trigger whenever possible

- Consider “stress-dose steroids” in any patient on chronic steroids or with chronic adrenal insufficiency to prevent adrenal crisis

- Tucci V, Sokari T. The clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of adrenal emergencies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014; 32(2): 465-484.

- Allolio B. Extensive expertise in endocrinology. Adrenal crisis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172(3):R115-24.

Should we treat strep throat in children with antibiotics?

- The NNT to prevent rheumatic fever for antibiotics in adult patients with strep throat in North America is approximately 1 in 10,000

- The NNH (number needed to harm) is approximately 1 in 15 (anaphylaxis, diarrhea including C.difficile)

- While there is a trend to withhold antibiotics for adults with strep throat, The Canadian Pediatric Society will be publishing guidelines this year likely recommending antibiotic treatment for children with strep throat because of the higher incidence of rheumatic fever compared to adults and in an effort to prevent PANDA (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder) that is associated with strep throat

- Duration of antibiotic treatment is 10 days to ensure complete eradication of strep

- Cohen JF, Cohen R, Levy C, et al. Selective testing strategies for diagnosing group A streptococcal infection in children with pharyngitis: a systematic review and prospective multicentre external validation study. CMAJ 2015; 187:23.

- McIsaac WJ, Kellner JD, Aufricht P, et al. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA 2004; 291:1587.

Occlusion posterior MI vs Non-occlusion posterior MI

- Only 0.5mm of ST depression in anterior precordial leads or ST elevation in posterior leads is required for the ECG diagnosis of posterior MI according to AHA guidelines, which is seen in 94% of patients with posterior MI

- That leaves 6% of patients with posterior MI who do not meet these criteria; hence a new paradigm in ECG diagnosis of posterior MI has been proposed: occlusion MI vs non-occlusion posterior MI

- A new tall anterior R wave may signify a posterior MI

- If the R:S ratio >1 in V2 and there is any ST depression in the anterior precordial leads, suspect posterior MI, perform serial ECGs and have a low threshold for consulting your cardiology colleagues

- Differential for R:S ratio >1 in V2 includes posterior MI, normal pediatric ECG, acute RV strain, RV hypertrophy, RBBB, WPW

1. Perloff JK. The recognition of strictly posterior myocardial infarction by conventional scalar electrocardiography. Circulation. 1964;30:706-18.

2. Boden WE, Kleiger RE, Gibson RS, et al. Electrocardiographic evolution of posterior acute myocardial infarction: importance of early precordial ST-segment depression. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59(8):782-7.

3. Pride YB, Tung P, Mohanavelu S, et al. Angiographic and clinical outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes presenting with isolated anterior ST-segment depression: a TRITON-TIMI 38 (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38) substudy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2010 Aug;3(8):806-11

4. Brady WJ, Erling B, Pollack M, Chan TC. Electrocardiographic manifestations: acute posterior wall myocardial infarction. J Emerg Med. 2001;20(4):391-401.

5. Khaw K, Moreyra AE, Tannenbaum AK, Hosler MN, Brewer TJ, Agarwal JB. Improved detection of posterior myocardial wall ischemia with the 15-lead electrocardiogram. Am Heart J. 1999;138(5 Pt 1):934-40.

6. Wung SF, Drew BJ. New electrocardiographic criteria for posterior wall acute myocardial ischemia validated by a percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty model of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001 Apr 15;87(8):970-4; A4.

7. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur Heart J 2019 Jan 14;40(3):237-269.

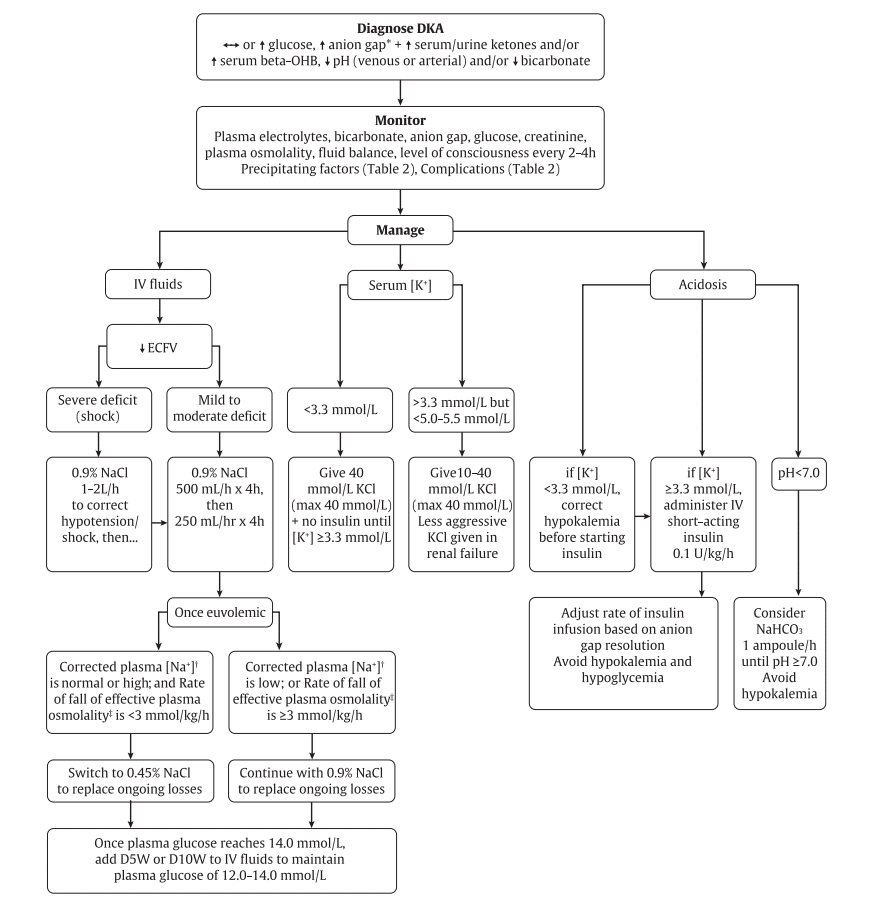

DKA – Just the Facts

- Diagnostic criteria for diabetic ketoacidosis are not well defined, however

- Serum pH and bicarbonate are usually low (≤7.30 and ≤15.0 mmol/L, respectively)

- Serum or urine ketones are usually positive

- Typically, the anion gap is elevated (>12 mmol/L) and serum blood glucose is high, but normal blood glucose does not preclude the diagnosis of DKA as euglycemic DKA may occur in specific instances (e.g., pregnancy, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor use, food restriction, and alcohol use).

- Negative urine ketones should not be used to rule out diabetic ketoacidosis, as urine tests measure the presence of acetoacetate, but not beta-hydroxybutyrate

- “5 I’s” mnemonic for DKA precipitants: infection, ischemia (e.g., myocardial, cerebral, and mesenteric), insulin omission, intoxication (e.g., alcohol and sympathomimetics), and iatrogenic (e.g., drugs or dextrose-containing infusions); additional causes include a new diabetes diagnosis, trauma, thyrotoxicosis, and other metabolic disorders

- Goals of initial DKA treatment are to:

- Correct fluid deficits (for non-shock patients, IV NS boluses of 500 mL/h should be initiated and may be repeated until euvolemic – usually for at least 4 hours – and then continued at 250 mL/h for 4 hours)

- Replace potassium (If serum K is <3.3 mmol/L, 40 mmol/L of KCl should be administered, and insulin should be withheld until levels are ≥3.3 mmol/L; if serum K is normal, 10–40 mmol/L KCl should be given in the IV fluid; if the patient is hyperkalemic, potassium should be withheld until less than 5.0–5.5 mmol/L and diuresis occurs; KCl should also be administered less aggressively to those with renal failure)

- Treat hyperglycemia (IV short-acting insulin therapy should begin at 0.1 units/kg/hour and adjusted based on the anion gap resolution while avoiding hypoglycemia or hypokalemia; insulin boluses are no longer recommended.)

- Treat acidemia (Sodium bicarbonate is not routinely recommended but may be considered for cases with severe acidemia (serum pH <7.0) or shock; insulin should be continued until acidosis and anion gap resolve)

- Yan JW, Spaic T, Liu S. Just the Facts: Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis in the emergency department. CJEM. 2020;22(1):19-22.

- Goguen, J, Gilbert, J; Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Hyperglycemic emergencies in adults. Can J Diabetes 2018;42 Suppl 1:S109–14.

Ovarian torsion imaging myths

Myth #1: Normal arterial flow on Doppler ultrasound rules out ovarian torsion.

- Normal Doppler US cannot rule out ovarian torsion

- Many cases of surgically confirmed ovarian torsion have completely normal venous and arterial blood flow

- The most common finding on US is an enlarged ovary (> 4 cm).

- Consider using a combination of US findings, such as abnormal vascular flow, free fluid on US, an ovary pushed towards the midline, or increased ovarian size.

Myth #2: CT of the abdomen/pelvis is not helpful in evaluation of suspected ovarian torsion.

- CT with IV contrast can suggest torsion.

- The most common finding on CT is an enlarged ovary. If this is found on CT and no other pathology is present, move to US.

- Other findings include an underlying ovarian lesion, lack of enhancement, inflammatory fat stranding around the ovary, free pelvic fluid surround the ovary, and twisting of the vascular pedicle.

- Robertson JJ, Long B, Koyfman A. Myths in the Evaluation and Management of Ovarian Torsion. J Emerg Med. 2017 Apr;52(4):449-456.

HINTS exam – how to use it properly

- The Head Impulse, Nystagmus, Test of Skew exam is indicated only in patients with continuous unremitting vertigo and nystagmus; do not perform the HINTS exam in patients with intermittent vertigo

- Head Impulse test is abnormal when there is an inability to maintain fixation during quick 30 degree head rotation with a corrective gaze shift after the head stops moving; an abnormal test is sensitive, but not specific, for a peripheral vestibular disorder (video of abnormal head impulse test indicating a peripheral cause); a normal response to the head impulse test indicated either normal or central cause

- Types of nystagmus that are almost always central: pure vertical, pure rotational, and multidirectional nystagmus (where the fast component changes direction depending on which direction the patient is looking).

- Types of nystagmus that are almost always peripheral: unidirectional horizontal nystagmus (fast component is in the same direction regardless of where the patient is looking), vertical rotational n ystagmus (the most common nystagmus seen in BPPV).

- Test of skew is positive in only 7% of patients with central cause of vertigo; a positive test indicates a central cause and is characterized by a vertical misalignment of the eyes when moving from covering one eye to the other

Update 2023: A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the diagnostic accuracy of physical exam findings for central versus peripheral causes in acute vertigo found that a general neurological examination had a sensitivity of 46.8% (95% CI 32.3-61.9%), and specificity of 92.8% (95% CI 75.7-98.1%). HINTS had a sensitivity of 92.9% (95% CI 79.1-97.9%), and specificity of 83.4% (95% CI 69.6-91.7%). HINTS+ (HINTS with hearing component) had the highest sensitivity at 99% (95% CI 73.6%-100%), and specificity of 84.8% (95% CI 70.1-93.0%). Abstract

<iframe width=”585″ height=”439″ src=”https://emcrit.org/?powerpress_embed=765-podcast&powerpress_player=html5video” frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no” webkitAllowFullScreen mozallowfullscreen allowFullScreen></iframe>

- Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009 Nov;40(11):3504-10.

- Newman-Toker DE, Kattah JC, Alvernia JE, Wang DZ. Normal head impulse test differentiates acute cerebellar strokes from vestibular neuritis. Neurology. 2008 Jun 10. 70(24 Pt 2):2378-85.

- Wong AM. Understanding skew deviation and a new clinical test to differentiate it from trochlear nerve palsy. J AAPOS. 2010;14(1):61-7.

Canadian CT head rule with Ian Stiell – how to use it properly

- The CT Head rule has been prospectively validated, undergone an implementation trial and meta-analysis, and when adhered to, may decrease the utilization of CT head and perhaps improve patient flow in the ED

- Exclusion criteria include age ≤16 years, patient on anticoagulant or antiplatelet agent and seizure after injury which raises the question: Do all patients on anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents who sustain a head injury require CT head imaging? According to Dr. Stiell while there is some evidence to suggest that patients taking oral anticoagulants may have a higher risk of intracranial bleeding, there is no good evidence that patients taking antiplatelet agents are at higher risk of bleeding; therefore, patients who fulfill the CT head rules taking antiplatelet agents do not require CT head imaging necessarily.

- In addition,

- One of the high risk criteria of the rule is age>65 which raises the question: Do all elderly patients who sustain a head injury require CT head imaging? According to Dr. Stiell, if a patient did not have a loss of consciousness, amnesia or confusion, regardless of age, they do not require a CT head

- CT c-spine should not automatically be added to CT head for all patients with head trauma; rather, separately assessing the c-spine using a validated decision tool is advised

Ottawa Rules app on Google Play

Canadian CT Head rule on MDCalc

- Smits M, Dippel DW, De haan GG, et al. External validation of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria for CT scanning in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005;294(12):1519-25.

- Sharp AL, Huang BZ, Tang T, et al. Implementation of the Canadian CT Head Rule and Its Association With Use of Computed Tomography Among Patients With Head Injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(1):54-63.e2.

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare

Regarding Canadian Head CT rules…too bad rules such as this do not take into consideration the medicolegal quagmire that is our healthcare system.

What of Continuous Glucose Monitoring Machines .

Are they reliable in this situation and others eg DKA

Re Pharyngitis there is another bacteria on the block :Fusobacterium necrophorum that can cause peritonsillar abscess in young adult smokers in particular and there is Streptococcus C

Penicillin is needed

Yes, what about the other rationales for treatment of strep throat: prevention of transmission, peritonsilar abscess, mastoiditis. Your recommendations are at odds with the CDC and IDSA