There are so many emergency airway controversies in emergency medicine! Dr. Jonathan Sherbino, Dr. Andrew Healey and Dr. Mark Mensour debate dozens of these controversies surrounding emergency airway management. A case of a patient presenting with decreased level of awareness provides the basis for a review of the importance, indications for, and best technique of bag-valve-mask (BVM) ventilation, as well as a discussion of how best to oxygenate patients. This is followed by a discussion of what factors to consider in deciding when to intubate and some of the myths of when to intubate. The next case, of a patient with severe head injury who presents with a seizure, is the fodder for a detailed discussion of Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI). Tips on preparation, pre-oxygenation and positioning are discussed, and some great debates over pre-treatment medications, induction agents and paralytic agents ensues. The new concept of Delayed Sequence Intubation is explained and critiqued. They review how to identify a difficult airway, how best to confirm tube placement and how to avoid post-intubation hypotension. In the last case of a morbidly obese asthmatic they debate the merits of awake intubation vs RSI vs sedation alone in a difficult airway situation and explain the best strategies of ventilation to avoid the dreaded bradysystlolic arrest in the pre-code asthmatic. Finally, some key strategies to help manage the morbidly obese patient’s airway effectively are reviewed.There are so many emergency airway controversies in emergency medicine! Dr. Jonathan Sherbino, Dr. Andrew Healy and Dr. Mark Mensour debate dozens of these controversies surrounding emergency airway management. A case of a patient presenting with decreased level of awareness provides the basis for a review of the importance, indications for, and best technique of bag-valve-mask (BVM) ventilation, as well as a discussion of how best to oxygenate patients. This is followed by a discussion of what factors to consider in deciding when to intubate and some of the myths of when to intubate. The next case, of a patient with severe head injury who presents with a seizure, is the fodder for a detailed discussion of Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI). Tips on preparation, pre-oxygenation and positioning are discussed, and some great debates over pre-treatment medications, induction agents and paralytic agents ensues. The new concept of Delayed Sequence Intubation is explained and critiqued. They review how to identify a difficult airway, how best to confirm tube placement and how to avoid post-intubation hypotension. In the last case of a morbidly obese asthmatic they debate the merits of awake intubation vs RSI vs sedation alone in a difficult airway situation and explain the best strategies of ventilation to avoid the dreaded bradysystlolic arrest in the pre-code asthmatic. Finally, some key strategies to help manage the morbidly obese patient’s airway effectively are reviewed.

Written Summary and blog post by Lucas Chartier, edited by Anton Helman October 2010

Cite this podcast as: Sherbino, J, Healey, A, Mensour, M, Helman, A. Emergency Airway Controversies. Emergency Medicine Cases. October, 2010. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/episode-8-emergency-airway-controversies/. Accessed [date].

In this episode on Emergency Airway Controversies, Dr. Sherbino, Dr. Healy and Dr. Mensour answer questions like: Does Delayed Sequence Intubation have a role in airway management? Which is the best induction agent for patients with head injury? Asthma? What are the pros and cons of Roccuronium vs Succinylcholine? What is the evidence for pre-treatment using lidocaine and fentanyl and head injured patients? Is the new drug Suggamadex useful? Should we be using Video Laryngoscopy (eg: Glidescope) as the primary tool for endotracheal intubation? What is the newest evidence for what constitutes a difficult airway? What are the best methods for confirming Endotracheal Tube placement? How can we best prevent and treat post-intubation hypotension? What is the best positioning for obese patients for intubation? What are the best ventilator settings for patients in status asthmaticus? and many more…..

General approach to patient with respiratory depression

- Transport patient to resuscitation area, notify the whole team (RNs, RTs, etc), and have all the equipment ready (IVs, advanced airways, cardiorespiratory monitors)

- Consider 500cc to 1L bolus IV of NS; consider 4‐point restraints before giving the naloxone to protect the patient and medical staff, as well as one attempt at bag‐valve‐mask ventilation (BVM) to rule out laryngospasm, which could cause negative pressure pulmonary edema if the patient inspires against a closed glottis once the naloxone is given

Oxygen delivery

Nasal prongs deliver only slightly more than the 21% of O2 containted in air because of the entrainment effect it creates, and “100% non‐rebreather mask” only delivers 65‐70% O2 at best To get better oxygenation, a better seal is needed, whether through BVM, non‐invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV), or endotracheal intubation

Tips for good BVM technique

- A health care provider (experienced with BVM) delegated exclusively to this task in order to perform it adequately (RR = 8‐12/min, not more!) with the right sized equipment, and consider using an oropharyngeal airway and/or 2 nasopharyngeal airways (trumpets)

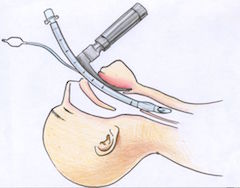

- 2‐handed, 2‐person technique (2 hands on the mask, and a second person squeezing the bag) is much more effective at opening up the airway by moving the mandible forward into the mask, i.e. jaw thrust, instead of driving the mask down on the face, which makes the soft tissue obstruct the airway

- Two methods for 2‐handed technique: (a) mirror image of what is usually done for onehanded technique (image 1), which allows 3 fingers per hand to lift the mandible;and (b) thenar eminences holding the mask with the thumbs in the direction of the patient’s feet, with 4 fingers per hand to lift the mandible (image 2)

- For bearded patients, consider putting a tegaderm patch on the beard (with a hole for ventilation!), or lubricant jelly in order to improve the seal; for edentulous patients, keep the dentures in for BVM (and remove for intubation), or put gauzes inside the cheeks

- Mnemonic for difficult BVM: BOOTS – Bearded, Obese, Old, Trauma (eg, obstruction), Stiffness (eg, OSA, COPD); also consider the effects of radiation therapy, which increases stiffness and decreases mouth opening

Indications for intubation

- General indications: obtain and maintain an airway in the setting of obstruction; correct deficient gas exchange (hypoxia or hypercarbia); prevent aspiration of blood, saliva, or other secretions; and predicted clinical deterioration

- Additional pearls

- Dogmatic approach like “GCS less than 8 means intubate” is inappropriate because it neglects the expected clinical course of the patient, and also because the GCS scores have only been validated in the setting of trauma (although GCS can still be used as a universal language to communicate with other team members)

- Patient not protecting his/her own airway is assessed by pooling of secretions in the oropharynx or absence of cough reflex; the presence or absence of gag reflex is not reliable (many elderly patients don’t have it at baseline, and shown to have no correlation with passive aspiration in patients undergoing swallowing studies)

- Other reasons to intubate: completely unresponsive patient with no expected early improvement; airway protection needed to decontaminate a patient with overdose; and severe sepsis and refractory shock, where the mechanical ventilation is meant to decrease the energy used by the patient for breathing, energy which can then be diverted towards other productive uses by the patient’s body

Sellick’s maneuver

- Cricoid pressure (different than BURP – see below) to prevent passive aspiration by occluding the esophagus against the vertebral bodies

- The evidence supporting it is poor: it does not decrease passive aspiration, it does not improve intubation success rates, it increases air trapping, it distorts of laryngopharyngeal landmarks, and it decreases venous return from the heart by occluding jugular veins

- In order to decrease the likelihood of aspiration, Sellick’s maneuver may be used but should be abandoned quickly if it impairs intubation attempts, and better techniques to avoid aspiration include keeping a low positive pressure during ventilation in order to decrease gastric insufflation

BURP maneuver

- Backwards, Upwards, Rightward Pressure used by intubator or assistant to improve laryngoscopic view by pushing the larynx towards the patient’s right while the laryngoscope pushes the tongue towards the patient’s left

Difficult airway

- Predictors of difficult laryngoscopy: LEMON

- Look externally for gestalt assessment of difficulty (not sensitive but quite specific) such as small mandible, large teeth, large tongue and short neck

- Evaluate 3‐3‐2, with 3 of patient’s own fingers between the teeth during mouth opening, 3 fingers of mandibular length between the chin and the hyoid bone, i.e. the base of the tongue, and 2 fingers between the hyoid bone and the thyroid cartilage

- Mallampati: Class I when all buccal structures visible with mouth opening and tongue out; Class II when tonsillar pillars not visible; Class III when minimal pharyngeal wall visible; Class IV when only palate visible

- Obstruction or Obesity

- Neck mobility: C‐spine collar or rheumatoid arthritis preventing C‐spine movement

- Predictors of successful intubation

- Experienced intubator, patient’s lack of muscle tone, optimal positionining of intubator and patient (see below), optimal blade length and type, adequate laryngeal manipulation (eg, BURP)

- 7 Ps of Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI)

- Preparation, Pre‐oxygenation, Pretreatment, Paralysis and induction, Position, Placement with proof, Postintubation management

Preparation

- SOAP ME: Suction, Oxygen, Airways (BVM, blades, with plan B and C – eg, Glidescope, Trach light, intubating LMA), Pharmacology, Monitors, Escape plan (anticipate 2‐3 steps down a worst‐case scenario for each individual patient)

Preoxygenation

- Non‐rebreather mask or BVM in order to replace the patient’s FRC (functional residual capacity) from nitrogen to oxygen, which will allow for more time before arterial desaturation

- Delayed Sequence Intubation (DSI):

- DSI is a form of procedural sedation for means of pre‐oxygenation with positive pressure ventilation when traditional pre‐oxygenation is unsuccessful (due to alveolar shunting seen in primary pulmonary or septic conditions)

- Method: insertion of behavioural control of the patient (i.e. calm him/her) before paralysis with ketamine sedation while still maintaining spontaneous respirations in order to tolerate oxygenation with PEEP (eg, CPAP), which will ultimately result in better pre‐oxygenation and better intubation conditions

for more on Delayed Sequence Intubation go to EMCrit website

Pretreatment (3min before induction)

- Lidocaine 1.5mg/kg IV used in reactive airway diseases and elevated intracranial pressure (ICP), but theevidence is poor

- Fentanyl 3μg/kg IV used in elevated ICP and patients with cardiovascular disease to prevent the reflex sympathetic response to laryngoscopy, which raises both heart rate and blood pressure

- Volume rehydration with 12cc/kg of crystalloid to correct the patient’s relative dehydration

- Avoiding hypotension, hypoxia and hypercarbia is even more important than the above methods, and therefore an individualized approach to each patient should be done (eg, if patient is hemodynamically unstable and propofol is the only available induction agent, then foregoing fentanyl would be reasonable as it will create even more hypotension)

- Non‐defasciculating dose of non‐depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agent (when succinylcholine will be used as the paralytic agent) should not be used as pretreatment

Update 2022: A multicenter RCT including 1067 critically ill patients undergoing intubation found that a 500mL fluid bolus prior to induction did not reduce the incidence of cardiovascular collapse (PREPARE II). Abstract.

Induction agent choices

- Etomidate (might lower seizure threshold), Ketamine (can be used in head‐injured patients as the concerns about raised ICP are unfounded), Propofol (probably best in the setting of seizures given antiepileptic properties, although it might cause hypotension), Ketofol (not recommended by EMC experts as an induction agent)

Update 2022: A multicenter prospective cohort study of 2760 critically ill patients undergoing tracheal intubation found that propofol use for induction was associated with peri-intubation cardiovascular instability/collapse (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.05-1.57), which was associated with increased risk of both ICU and 28 day mortality (INTUBE study). Abstract

Update 2022: A retrospective cohort study of 469 patients who had undergone emergent intubation with either etomidate or ketamine induction did not find an association between the incidence of post-intubation hypotension and choice of induction agent (aOR 1.45, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.65). Abstract

Update 2022: A prospective, randomized, open-lab, parallel assignment, single center trial with 801 critically ill patients requiring emergency intubation found that survival at day 7 was significantly lower in those who received etomidate compared to ketamine (77.3% vs 85.1%), but day 28 survival rates were not significantly different (etomidate 64.1%, ketamine 66.8%). Abstract

Paralytic agent choices

- Neurologic assessment needs to be performed before paralysis in order to assess serial changes, including GCS score (including best motor response), pupillary size and reaction, and reflexes

- The 3 EMC experts use rocuronium (1mg/kg) because of the lack of contraindications attached to succinylcholine (SCh), and they feel that the longer time to action (60sec compared to the 45sec of SCh) is not clinically significant; moreover, they feel that the longer time of action (40‐60min compared to 7min) is irrelevant because the patient will need paralysis to go to the CT scan, and the neurological status of the patient cannot have changed so dramatically that another neurological assessment is necessary within minutes of intubation

- Suggamadex is a new medication that completely reverses the effects of rocuronium in 1‐2min at a dose of 4mg/kg; in most cases, however, unlikely that reversal of paralysis is needed immediately after intubation

- Succinylcholine (dose of 1.5mg/kg) is favoured by the Cochrane database for RSI due to better intubating conditions and less post‐paralysis pain, but contraindications need to be remembered: hyperkalemia (eg, dialysis); burns, crush injuries and neurological dysfunction (eg, stroke) starting at 5 days after the insult

Positioning

- Optimal position: bed at the level of the intubator’s belt line, straight back and arms at a distance from the patient, holding the laryngoscope blade at the base of the handle, with the appropriate blade type (curved blade allows for better tongue control, but straight may be used if attempt is unsuccessful with straight blade)

- Optimal patient position: sniffing position (although simple head extension without lower C‐spine flexion may be just as good); for trauma patients, C‐collar removed while assistant is providing manual in‐line stabilization from below, to allow for movement of the mandible forward and optimization of the glottic view

- Consider using adjuncts – Video laryngoscope (which may lead to less C‐spine mobilization than direct laryngoscopy), Trach light (light wand), intubating LMA or fiberoptic scope – and don’t repeat the exact same sequence twice if you fail: something has to be changed to provide better intubating condition and be successful

Update 2017: A recent prospective observational study by Turner et al. (2017) has shown elevating the head of the bed, particularly to ≥45degrees, helps facilitate first-pass success for endotracheal intubation performed by residents in the ED. This correlates with recent literature questioning the traditional supine method – which suggests head-elevated positioning improves pre-oxygenation, glottic view, and reduces risk of intubation complications. Abstract

Update 2022: A retrospective analysis of 2139 intubations in French ICUs found that the incidence of first-pass intubation success was significantly higher when using a Macintosh 3 laryngoscopy blade compared to a Macintosh 4 blade (79.5% vs 72.3%, p = 0.0025). Abstract

Medications for Airway Management card PDF 2017

Placement with proof

- Reference standards: End‐tidal CO2 monitoring, either with capnography (number and waveform) or colorimetric (Yellow color = “Yes”, and purple = “The colour of the patient when tube in the wrong place”, but has a 4‐7% failure rate) – ETCO2 will be negative in ⅓ of cardiac arrests due to lack of cardiac output; anotherconfirmation method is confidently seeing the endotracheal tube going through the vocal cords confirmation method is confidently seeing the endotracheal tube going through the vocal cords

- Other methods: Esophageal detector device (squeeze the bulb and apply to tube – it will stay collapsed if in the esophagus, but pop open if in the trachea), auscultation, misting of the tube

- Placement of the tube at 21cm of length at the upper teeth (or alveolar ridge if edentulous) in women will result in the tip being at 3cm from the carina in 95% of individuals; the number in males is 23cm

Immediate postintubation management

- First step: adequate analgesia with fentanyl 25‐50μg IV q5min PRN based on vital signs

- Second step: sedation (especially if patient paralyzed) with midazolam 5mg (±2mg depending on patient’s weight and hemodynamics) or lorazepam 1‐2mg IV puss; assess degree of sedation with facial muscle tension, movements and increased heart rate and blood pressure

- Third step: start propofol or midazolam drip, volume resuscitation, NG tube, consider using ketamine or phenylephrine IV push for hypotension, and wrist restraints in case the patient wakes up

Tips for emergency airway management of obese patients

- Optimize preoxygenation because of RAPID desaturation (decreased FRC and increased metabolic rate, with resting hypoxemia and hypercapnia even without underlying lung pathology), higher likelihood for and worse consequences from aspiration (larger gastric volumes with lower pH); all of BVM, laryngoscopy, intubation and surgical airway will be difficult, so prepare plans B and C (and D)

- Consider putting a “ramp of blankets” under obese patients (eg, 7 blankets under the occiput, 5 under the shoulder and 3 under the scapula) so that the external auditory canal is on an horizontal line with the sternum, as well as reverse Trendelenburg position (to push the abdominal content away from the lungs)

- Remember that other types of patients also desaturate quickly: pregnant, extremes of age, CHF, COPDIn the setting of severe asthma:

- In the setting of severe asthma:

- Intubate only if all treatment modalities have been optimized and are still unsuccessful – getting the air out of the lungs is the patient’s problem and a ETT will likely not help so much for that; eg, patient is peri‐arrest and will go into PEA if not intubated (have ENT or anesthesia back‐up present), and consider using ketamine

For EM Cases main episode on Managing Obese Patients with Rich Levitan, Andrew Sloas and David Barbic go to Episode 69

Ventilation of the asthmatic or COPD patient

- Permissive hypercapnia: low tidal volume, low plateau pressure and low peak inspiratory pressure in order to protect the lungs from barotrauma and ventilator‐induced lung injury, with low respiratory rate and long expiratory phase in order prevent air trapping, hyperinflation and subsequent cardiovascular compromise; results in higher than normal CO2 and lower than normal pH (down to 7.2)

- If an episode of hypotension occurs, you should (1) disconnect the patient from the ventilator to allow for full exhalation of the air that is likely trapped (manual chest pressure may help), (2) assess the DOPE mnemonic – Displacement of tube, Obstruction of tube, Pneumothorax and Equipment failure

- Do not forget to continue standard therapies such as volume resuscitation, inhaled bronchodilators, and consider using inhaled anesthetics in the OR as a last ditch effort

Airway poster for your ED by Dr. Caroline Shooner summarizing all EM Cases airway related resources

For more on airway management on EM Cases:

Episode 54: Preoxygenation and Delayed Sequence Intubation

Ep 110 Airway Pitfalls – Live from EMU 2018

Best Case Ever 39 – Airway Strategy & Mental Preparedness in EM Procedures

Best Case Ever 57 PREPARE mnemonic for Airway Management

Best Case Ever 62 Penetrating Upper Airway Injury Awake Intubation Do’s & Don’ts

CritCases 6 – Airway Obstruction

Dr. Sherbino, Dr. Helman, Dr. Healy and Dr. Mensour have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Key References

Walls RM, Murphy MF. Manual of Emergency Airway Management. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Ovassapian A, Salem MR. Sellick’s maneuver: to do or not do. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(5):1360-2.

Snider DD et al. The “BURP” maneuver worsens the glottic view when applied in combination with cricoid pressure. Can J Anaesth 2005 Jan; 52:100-4.

El-Orbany M, Woehlck HJ. Difficult mask ventilation. Anesth Analg. 2009 Dec;109(6):1870-80.

Ni chonghaile M, Higgins B, Laffey JG. Permissive hypercapnia: role in protective lung ventilatory strategies. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11(1):56-62.

Emergency ventillation in 11 minutes by Reuben Strayer

https://vimeo.com/34883844

Now test your knowledge with a quiz.

Leave A Comment