Topics in this EM Quick Hits podcast

Anand Swaminathan on continuous quantitative end-tidal CO2 monitoring in cardiac arrest (2:30)

Tahara Bhate in QI Corner – sorting out the the dizzy patient (10:00)

Andrew Healey on organ donation do’s and don’ts (20:00)

Sarah Foohey on foodcourt hacks – paraphimosis, rectal prolapse, food bolus obstruction (28:10)

Jennifer C. Tang on 4 medicolegal myths (35:55)

Podcast production, editing and sound design by Anton Helman, January 2023

Podcast content, written summary & blog post by Anton Helman and Sarah Foohey, January 2023

Cite this podcast as: Helman, A. Swaminathan, Bhate, T. Healey, A. Foohey, S. Tang, JC. EM Quick Hits 45 – ETCO2, Organ Donation, Paraphimosis, Medicolegal Myths, QI Corner. Emergency Medicine Cases. January, 2023. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-january-2023/. Accessed April 23, 2024.

Value of continuous waveform quantitative end-tidal CO2 monitoring in cardiac arrest

- A sudden decrease or loss of ETCO2 may indicated the need for CPR to be started

- ETCO2 is an indirect assessment of quality of chest compressions (location, rate, depth); adequate chest compressions correlate with ETCO2 pressures of ≥20mmHg.

- A rise of ETCO2 >20mmHg is highly specific for ROSC in patients with PEA arrest; on average, patients with ROSC after CPR had an average ETCO2 level of 25 mmHg in one meta-analysis

- An up-trending ETCO2 during resuscitation suggests continuing resuscitative efforts unless there is overwhelming clinical evidence to the contrary

- Confirmation of airway placement and subsequent guide for adequate delivery of breaths using BVM or supraglottic device and ventilation rates for ETT with more immediate feedback than oxygen saturation monitoring

- A general “rule” is that if the ETCO2 is consistently <10mmHg for 3-5 minutes after 20 minutes of high quality CPR and resuscitative efforts, ROSC is unlikely to be achieved; however this is not a sensitive test and should be used only as an adjunctive data point in decisions of termination of resuscitation efforts

- There are multiple potential confounders that can elevate or decrease ETCO2 levels (see chart below), so extreme or trending values may be more useful than unwavering mid-range levels

- A sudden flattening of the ETCO2 waveform may be due to cardiac arrest, ventilator disconnection, esophageal intubation, capnography obstruction or dislodged airway device

Factors Affecting EtCO2

Source: EMSWorld

- Kodali, B. Urman, R. Capnography during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Current evidence and future directions. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2014 Oct-Dec: 7(4): 332-340.

- Crickmer M, Drennan IR, Turner L, Cheskes S. The association between end-tidal CO2 and return of spontaneous circulation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity. Resuscitation. 2021 Oct;167:76-81.

- Skulec, R., Vojtisek, P. & Cerny, V. Correlation between end-tidal carbon dioxide and the degree of compression of heart cavities measured by transthoracic echocardiography during cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit Care 23, 334 (2019).

- Wang, AY. Initial end-tidal CO2 partial pressure predicts outcomes of in-hospital cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg Med. 2016 Dec;34(12):2367-2371.

- Venkatesh, H. Keating, E. Can the value of end tidal CO2 prognosticate ROSC in patients coding into emergency department with an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Emerg Med J. 2017 Mar; 34(3): 187-189.

- Paiva EF, Paxton JH, O’Neil BJ. The use of end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) measurement to guide management of cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2018;123:1–7.

- Darocha T, Debaty G, Ageron FX, Podsiadło P, Hutin A, Hymczak H, Blancher M, Kosiński S, Mendrala K, Carron PN, Lamhaut L, Bouzat P, Pasquier M. Hypothermia is associated with a low ETCO2 and low pH-stat PaCO2 in refractory cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2022 May;174:83-90

QI Corner – Dizziness, vertigo, pre-syncope and pulmonary embolism

- Recognize the margin of error in asking patients to categorize their dizziness as vertigo or presyncope and consider employing a timing and triggers-based assessment to help avoid discarding half the differential diagnosis prematurely

- Stay alert to the possibility of pulmonary embolism in patients with COPD and pre-syncope or syncope even though studies have over-estimated the prevalence of PE in such populations

- Make an effort to track down EMS ECG strips in patients with pre-syncope or syncope, and consider working with your hospital and EMS to develop a system that archives EMS ECGs

- Couturaud F, Bertoletti L, Pastre J, Roy PM, Le Mao R, Gagnadoux F, Paleiron N, Schmidt J, Sanchez O, De Magalhaes E, Kamara M, Hoffmann C, Bressollette L, Nonent M, Tromeur C, Salaun PY, Barillot S, Gatineau F, Mismetti P, Girard P, Lacut K, Lemarié CA, Meyer G, Leroyer C; PEP Investigators. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism Among Patients With COPD Hospitalized With Acutely Worsening Respiratory Symptoms. JAMA. 2021 Jan 5;325(1):59-68.

- Saccomano SJ. Dizziness, vertigo, and presyncope: what’s the difference? Nurse Pract. 2012 Dec 10;37(12):46-52.

- https://emergencymedicinecases.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Himmel-Vertigo-Summary-2017.pdf

- Anand Swaminathan, “The True Prevalence of PE in ED Syncope Patients”, REBEL EM blog, February 11, 2019. Available at: https://rebelem.com/the-true-prevalence-of-pe-in-ed-syncope-patients/.

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Sivilotti M, Rowe B, et al. Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism Among Emergency Department Patients With Syncope: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med. January 2019.

- Aleva FE, Voets LWLM, Simons SO, de Mast Q, van der Ven AJAM, Heijdra YF. Prevalence and Localization of Pulmonary Embolism in Unexplained Acute Exacerbations of COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest. 2017 Mar;151(3):544-554.

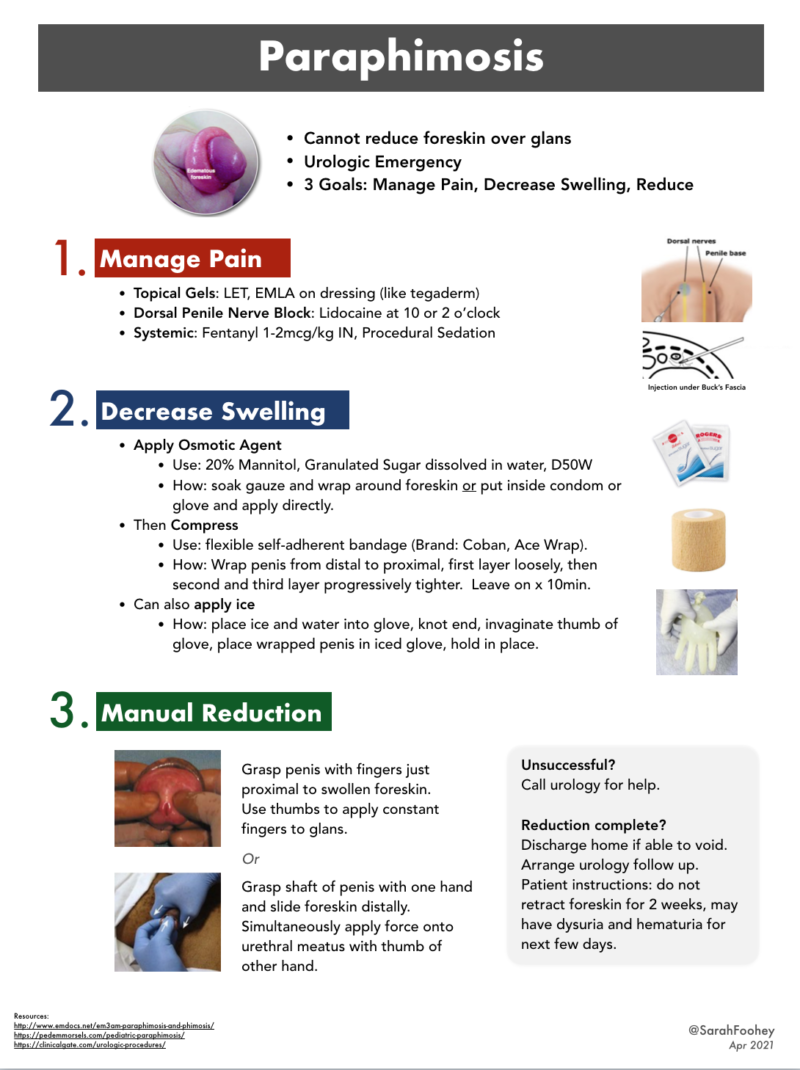

Foodcourt hacks – paraphimosis, rectal prolapse, food bolus obstruction (Best of University of Toronto EM)

Best of University of Toronto

- Consider granulated sugar dissolved in water to create an osmotic solution to reduce foreskin swelling in the management of paraphimosis

- Similarly, apply granulated sugar/sugar solution to rectal prolapse tissue to reduce swelling before attempting reduction

- Consider using a carbonated beverage (like Coke or Pepsi) to help manage a stable patient with esophageal food bolus obstruction when endoscopy is not immediately available, as long as the patient understands that this practice is based on case studies and not on official guidelines

- Kerwat R, Shandall A, Stephenson B. Reduction of paraphimosis with granulated sugar. Br J Urol. 1998;82(5):755.

- Myers JO, Rothenberger DA. Sugar in the reduction of incarcerated prolapsed bowel. Report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991 May;34(5):416-8.

- Demirel AH, Ongoren AU, Kapan M, Karaoglu N. Sugar application in reduction of incarcerated prolapsed rectum. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jul-Aug;26(4):196-7.

- Baerends EP, Boeije T, Van Capelle A, Mullaart-Jansen NE, Burg MD, Bredenoord AJ. Cola therapy for oesophageal food bolus impactions a case series. Afr J Emerg Med. 2019 Mar;9(1):41-44.

- Karanjia ND, Rees M. The use of Coca-Cola in the management of bolus obstruction in benign oesophageal stricture. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993 Mar;75(2):94-5.

- Sarkar PK. The use of Coca-Cola in the management of bolus obstruction in benign oesophageal stricture. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993 Sep;75(5):377.

Organ donation do’s and don’ts

The opportunity to provide the gift of organ donation occurs rarely in our health care systems and must be preserved, even in states of surge.

3 major tasks of organ donation in the ED

- Be clear about our role as EM physicians and communicate this with the family of the patient in an empathic manner e.g. “what we know now is that we have a catastrophically, very likely irreversibly injured brain in a patient who is physiologically supported, and that this injury is not reversible; we will provide physiological support until the next step in care”; avoid the terms dead and death

- Physiologically support the patient (e.g. ongoing ventilatory care, hemodynamic support including monitoring end-organ perfusion, head of bed at 30 degrees, monitor neurologic status) while preserving the opportunity for them to consider organ donation

- Connect with critical care team for a formal determination of prognostication – engage the critical care team who will provide ongoing support of the patient and family until a formal prognosis can be ascertained (and determine if patient meets criteria for neurologic death by examination), and during which time contact with organ donation organization can be made based on shared decision making and determination of death

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare

Excellent session

Can you please do one on assessing capacity in mentally ill suicidal patients with overdose, how to do check capacity

Thank you Dr Healy for the very important discussion of organ donation. I personally disagree with the avoidance of the word ‘death’ in early family discussions. It’s the number one question they want answered and I think skirting around it perpetuates our whole clinician discomfort with death and dying which we inadvertently push onto the family. Labelling it and identifying that it is our greatest concern may be a lot healthier and help create an environment of support and open discussion than saying nothing of it and kicking the can down the road. I also acknowledge there are a lot of cultural nuances to this sensitive topic so my practise (in Australia) may differ significantly to North America. Thank you for bringing this discussion to the fore, it was very informative.

Alex –

Thanks for this comment. I agree with you. What I mean about avoiding the word death should be further clarified. If the patient is dead (by neurological or circulatory criteria), we should absolutely be clear about this and provide that information. When things are uncertain, we should not say the patient is “pretty close to dead” or “basically dead” or “almost dead” as that language is confusing for families. In my view, we should provide clear and accurate information about what is known now and not suppose the result of a careful examination for neurological criteria prior to it being completed. I suspect our practice is actually very similar.

Thanks for your comment and for listening!

awesome as always!!

Just wondering about a food bolus stuck in the esophagus, can you please give clear signs of when the patient needs an urgent endoscopy?

Obviously, if there’s any ‘airway compromise’ ( ie stridor, tachypnea, etc.) but what else can we say to convince our endoscopy colleagues that they need to come to scope this patient?

I just used Glucagon, Valium and Pepsi to have a patient. The Patient vomited the steak out. Thanks for the coke trick.