In this CritCases blog – a collaboration between STARS Air Ambulance Service, Mike Betzner and EM Cases, Mike Misch presents a case of a patient with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) with a postoperative acute lower GI bleed and answers practical questions such as: How do you measure blood pressure in a patient with an LVAD? What are the common complications of LVADs that we must be aware of? What information can the LVAD controller provide? Why are LVAD patients at high risk for bleeding? and many more…

Written by Michael Misch, Edited by Anton Helman, October 2018

The Case

A 62-year old male presents to your community ED with brisk bright red blood per rectum. He had a prostate biopsy 2 days prior as part of a work-up for an elevated PSA. He had a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) placed due to severe left ventricular dysfunction 6 months ago following a myocardial infarction. His bleeding started 6 hours ago and he estimates passing a liter of blood per rectum.

His Medications are Ramipril, Atorvastatin, ASA, Warfarin and Lasix.

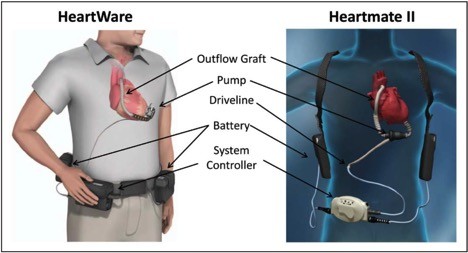

While previously a bridge to cardiac transplant in hospitalized patients, LVADs are now increasingly used as a form a definitive therapy for advanced heart failure. These patients are best cared for at their LVAD center, but they may present to your ED so it is critical to have a basic understanding of their function and the issues that can arise when caring for these patients.

All LVADs function as a separate circuit, pumping blood from the left ventricle to the aorta. The pump is connected via a driveline externally through the skin to a controller which houses the electronics and monitors pump function. This is often connected to two battery packs holstered on the patient’s shoulders.

On exam, the patient is alert but looks very unwell. He is diaphoretic and pale. Vitals are T 36.4, O2 Sat 95%, RR 20. The nurse was unable to get a BP at triage. There are absent pulses both peripherally and at the carotid. Cap refill is 2 seconds. You are unable to auscultate heart sounds but a mechanical hum is heard. Chest is clear. Abdominal exam is benign. Digital rectal exam reveals copious bright red blood with clots.

How does an LVAD change your physical exam? How do you measure blood pressure?

Current generation LVADs use a propeller-type mechanism (technically called an impellar) creating constant non-pulsatile blood flow through the circuit. As such, these patients often lack palpable pulses and essentially live in a hemodynamically stable pseudo-PEA state. Heart sounds are usually absent. Instead, listen for a hum over the precordium to confirm the pump is working. An absent hum would be incredibly concerning as it suggests pump failure.

Automated BP cuffs, which rely on biphasic blood flow, can only detect a BP half of the time. In stable patients, use a manual sphygmomanometer and a doppler probe. If a pulsatile sound is heard on doppler, the blood pressure obtained represents systolic blood pressure. If a non-pulsatile constant “swoosh” is heard, this number represents MAP and should be between 70-90 mmHg. Unstable patients need an arterial line, which will have to be placed using ultrasound guidance, as there will be no pulse to guide you. In the meantime, look for other perfusion indicators such as capillary refill, mottling, extremity temperature and mental status. Oxygen saturation probes similarly rely on pulsatile blood flow and may also be unreliable, however if you do obtain a normal Oxygen saturation it is likely accurate.

Case continued

The community ER physician has assessed the patient and started a 1 L normal saline bolus while awaiting uncross matched blood from the blood bank. She estimates a liter of blood loss per rectum over the last 30 minutes and calls for transfer to tertiary centre, which is a 1-hour flight away.

What can go wrong with the LVAD pump that might be complicating this patient’s presentation?

Thrombosis

Like patients with mechanical valves, LVADs are at risk of thrombosis. The presentation varies quite widely from increased pump power consumption and pump overheating to pump failure, cardiogenic shock, and death. Thrombosis can also present as distal embolization causing stroke, limb or intestinal ischemia. The presence of pump thrombosis can be assessed by echocardiogram but will also be suggested by poor pump performance and increased power requirements. Treatment options include IV heparin and thrombolytics.

Suction Events

During hypovolemia or dysrhythmias, the negative pressure generated by the LVAD that pulls blood from the LV to the aorta can cause collapse of the LV wall. This causes decreased flow through the LVAD and decreased cardiac output. The LVAD controller can often detect these events and will attempt to decrease the pump speed to account for this. In the meantime, the treatment is to optimize preload and get an ECG to identify any possible dysrhythmias that could be decreased cardiac output (ie. Vtach, Vfib).

Pump Failure

An absent hum on auscultation suggests pump failure. Whether due to pump thrombosis or other mechanical failure, these patients will likely present in cardiogenic shock and should be treated with inotropes and vasopressors as if there was no LVAD present.

What are your initial investigations and management for this LVAD patient with a GI bleed?

This patient is coagulopathic and presenting with a brisk lower GI Bleed. Obtain CBC, INR/PTT, group and screen and cross and type for 4 units of red cells. Give O positive blood while awaiting cross and type. If your hospital has a massive transfusion protocol, this would be a good time to consider activating it. The patient is also at risk for cardiac ischemia as well as sepsis (especially since the patient recently had a prostate biopsy). An ECG is especially important as patients with LVADs can develop VTach and even VFib with preserved cardiac output, but will eventually decompensate. Yes, you can cardiovert and defibrillate patients with LVADs but avoid placing the pads directly over the LVAD.

These devices are dependent on adequate preload so volume needs to be given. The volume I’d use is blood, plasma and platelets. Having him hypotensive AND anemic is a terrible combination… Blood products and minimal crystalloid are the hallmark of treating this guy until something definitive can be done.

-Saul Pytka MD, FRCPC

Associate Professor of Anesthesiology (Clinical)

University of CalgarySomething more than blood loss may be happening to him since he clinically is unwell. Despite him being afebrile, I would give him a dose of ceftriaxone due to high risk of bacteremia in the biopsy procedure.

-Eddie Chang MD FRCPC

Case continued

A VBG and ECG are obtained. A point of care INR is 3.8.

| pH | 7.2 |

| pC02 | 33 |

| HCO3 | 18 |

| Hb | 86 |

| Lactate | 3.6 |

| Glu | 4.2 |

ECG is shown above. Sinus rhythm with RBB, similar to previous.

The transport team including a physician and RN arrive. Your patient’s MAP is 60 mmHg by doppler. He has received 1 L of NS bolus and now has 2 units of 0 positive blood via rapid infuser. Ceftriaxone and metronidazole have been given to cover for possible sepsis.

POCUS can help to assess the patient intravascular volume and pump status:

- Small RV with collapsible IVC – patient needs volume, in this case RBCs.

- Dilated RV with small LV – Consider PE or RV MI

- Dilated RV and Dilated LV – pump failure or thrombosis

POCUS shows a collapsible IVC under 2 cm as well as RV collapsibility. The JVP, also visualized by ultrasound, is at the sternal notch. All these confirm that the patient needs more volume.

What information can the LVAD controller provide?

You are not an expert in troubleshooting LVADs, but you should be on the phone with someone who is. Contact the patient’s LVAD center as soon as possible – there should always be someone on call to help. A few questions to ask yourself:

Are all connections secure? Is the controller hot? Overheating would suggest there may be a pump malfunction or pump thrombosis. If there are any issues with LVAD connections, this might be easily fixed and should not missed.

Are there signs of infection at the driveline site at the skin? Sepsis from driveline infections are common in these patients.

What does the monitor display? While it might be daunting to try to interpret the LVAD monitor there are usually a few parameters your LVAD physician will want to know:

- Pump Speed (Normally 3 – 10 RPMs)* This is pre-set to optimize LV filling without the development of suction events (where the negative pressure is from LV)

- Flow (Normally 2 – 7 L/min)* An estimation of flow through pump based on the pump speed, power and the hematocrit.

- Power (Normally 3 – 7 Watts)* Correlates with device flow. But if power increases relative to flow, this can suggest pump thrombosis.

- Pulsatility Index (1 – 10). A measure of how much the hearts native contraction contributes to cardiac output. If low, suggest hypovolemia or poor native LV function.

- Alarms. The controller will alarm if there is low battery, suction events, low flow, high power usage, which can aide in trouble-shooting the LVAD.

*Precise normal values are device-specific.

At the very least, you will be able to relay this information to the LVAD team who can help inform next steps. A very helpful resource for trouble-shooting LVADs for emergency providers can be found below. This link provides access to succinct instruction on how to assess an LVAD from each manufacturer.

https://www.mylvad.com/medical-professionals/resource-library/ems-field-guides

The VAD was set to 2700 rpm with a calculated flow of 5.4L. The controller was not warm to touch, there were no signs of infection at the driveline site at the skin. A page is placed to the patient’s LVAD center to help guide management and help to arrange transfer.

Why are LVAD patients at increased risk for bleeding?

The patient recently had a prostate biopsy. While the risk of serious post procedural rectal bleeding is low in most patients, LVAD patients are at increased risk of life-threatening bleeding for multiple reasons:

- Anticoagulation/Antithrombotic. Patients with LVADs are usually on daily ASA 81 mg along with warfarin with a target INR of 2.0-3.0.

- Thrombocytopenia and Platelet Dysfunction. The shear force from the LVAD’s impellar causes pancytopenia. Additionally, von Willebrand Factor (vWF) is a large molecule that is also sheared by the impellar, causing an acquired von Willebrand Disease from vWF deficiency.

- Arterovenous Malformations (AVMs). The most common cause of GI bleeding in patients with LVADs are AVMs. They are thought to arise from absent pulsatile flow and can cause serious, sometimes life-threatening bleeding.

Case continued

Your patient has been given a total of 2 units of red cells. Their MAP is now 70 mmHg and you are preparing to transport the patient to their LVAD center.

Will you reverse this LVAD patients anticoagulation?

No, I would not reverse him at this stage. IVAD patency is more important than bleeding currently. I would resuscitate him more, consider TXA, give more blood if needed and volume.

-Dr Jamin Mulvey

FANZCA

Like all interventions, it is a balance of risks. In short, patients with an LVAD who present with immediate life-threatening bleeding, not responding to other measures, can have their anticoagulation reversed. LVAD patients with bleeding complications in whom their antiplatelet or anticoagulant have been held for weeks still have a low rate of thrombosis. However, LVAD thrombosis can have devastating complications, so this decision should be made in consultation with the patients LVAD physician. This patient is responding to red cell transfusion, suggesting that reversal of anticoagulation may not be necessary. In the meantime, emphasis should be placed on aggressively supporting the patient’s hemodynamics as part of a balanced transfusion protocol with platelets and FFP. You can consider tranexamic acid as well, as you might in other bleeding patients. However, definitive treatment will likely need hemorrhage control via endoscopy or colonoscopy. Given that these patients are likely to have aVWD, there may be a role for desmopressin but this has not been well-studied in the acutely bleeding patient.

Case continued

The plan is to transport your patient via fixed wing to the tertiary center with a physician on board and blood products to transfuse as necessary. Given that your patient has responded to volume, the patient’s cardiologist has recommended not to reverse the anticoagulation.

Any other thoughts on how to stop bleeding in this LVAD patient?

I would place a rectal balloon (used in ICU in severely fecally incontinent patients) or if they didn’t have one, a Linton tube, and to inflate it with 200-300 cc of saline in the rectal vault and then gently yank on it to make sure it was well seated. This is in the hopes of tamponading the bleeding, which presumably was coming from the biopsy site.

Michael J. Betzner MD FRCPC

Medical Director STARS Calgary

Presumably, this patient is bleeding from their prostate biopsy site. Attempts to tamponade rectal bleeding have been described, including rectal packing or rectal balloon, however use of a Linton or Blakemore tube is an option in difficult to control bleeding, while awaiting definitive management.

Case Resolution

Your patient arrives at the LVAD center, receiving a total of 4 Units of RBCs. A Linton tube is inserted prior to departure. Afterward there was only scant bleeding en route. He undergoes colonoscopy shortly after arrival. There is no active bleeding at the time of endoscopy, but the source of bleeding is identified on rectal mucosa adjacent to the prostate. They are clipped. The patient did not require reversal of his anticoagulation. He was discharged from hospital a few days later.

Take Home Points for Management of LVAD in the GI Bleed Patient

- Patients with LVADs are increasingly able to live independently in the community and may present to your ED. Call for help early when they do.

- Assessment of hemodynamic status in patients with LVADs is made difficult by the fact that they live in a stable “pseudo-PEA” state.

- On initial assessment, check for perfusion by assessing mental status, capillary refill and colour/temperature of extremities. Listen for a hum over heart to ensure the pump is working. Check all connections, inspect the controller overheating, look for signs of infection at the driveline. POCUS can aid in assessment of volume status/pump function.

- Patients with LVADs are preload dependent so replace volume if there is any suspicion of hypovolemia.

- Patients with LVADs are at significant bleeding risk, including gastrointestinal, intracranial hemorrhage and bleeding at the LVAD site itself.

- Patients with life-threatening bleeding refractory to other measures can have their anticoagulation reversed, but this carries the risk of pump thrombosis. Involve the patient’s LVAD team in this decision whenever possible.

Drs. Helman and Misch have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

Hollis IB, Chen SL, Chang PP, Katz JN. Inhaled Desmopressin for Refractory Gastrointestinal Bleeding in a Patient With a HeartMate II Left Ventricular Assist Device. ASAIO J. 2017;63(4):e47-e49.

Michopoulou AT, Doulgerakis GE, Pierrakakis SK. Sengstaken-Blakemore tube for massive haemorrhage following rectal biopsies. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28(11):1595-6.

Nassif ME, Larue SJ, Raymer DS, et al. Relationship Between Anticoagulation Intensity and Thrombotic or Bleeding Outcomes Among Outpatients With Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(5)

Partyka C, Taylor B. Review article: ventricular assist devices in the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26(2):104-12.

Peberdy MA, Gluck JA, Ornato JP, et al. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Adults and Children With Mechanical Circulatory Support: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(24):e1115-e1134.

Other FOAMed Resources on LVAD management

https://emcrit.org/emcrit/left-ventricular-assist-devices-lvads-2/

http://rebelem.com/left-ventricular-assist-device/

Other EM Cases Resources on GI bleed emergencies, transfusions and reversal of anticoagulants

as always, great points…